In which rival strategic visions lead to the arrival of John Pope, good for no one

.....................................................................................................................................................

June 26 is best known as Robert E. Lee's first offensive with the Army of Northern Virginia, and the second day of the Seven Days, the spectacular offensive that reversed the war's strategic situation and began the legend of Lee. But for Maj. General Irvin McDowell, lately commanding the Department of the Rappahannock, it was another day when his dreams of rehabilitation and glorious military command were yanked from him.

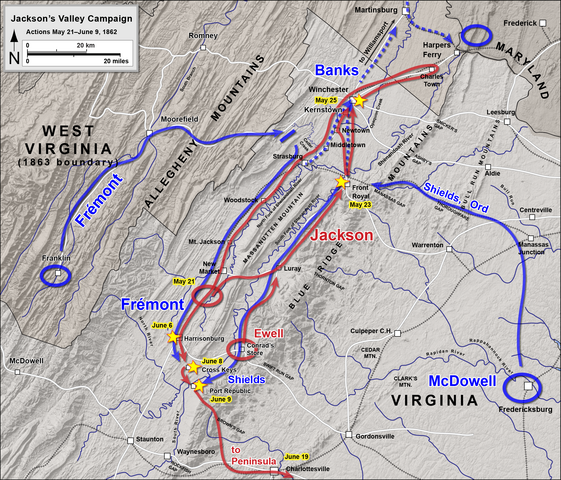

The Confederate Maj. General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson and his second-in-command, Maj. General Dick Ewell, had over the month of May upended all the carefully restored order from the banks of the Potomac to the Allegheny Mountains with a campaign that had made fools of the Union commanders he faced (all that had saved their careers thus far was that the size of Jackson's army remained greatly exaggerated). McDowell, with authority over all of northern Virginia, but only west to the Blue Ridge Mountains, had initially resisted having men from his department dragged into the affair, then pledged to solve the problem the other generals couldn't, then when it appeared clear the situation had been defused again tried to extricate his command from it. Jackson's twin victories at Cross Keys and Port Republic only further cemented in McDowell's mind that his men should never have been involved.

Where McDowell's men belonged, in McDowell's mind was not Front Royal, not Manassas Junction, not even Fredericksburg, but outside Richmond with the rest of the Army of the Potomac, from which his command had been carved. That's where the war was being one, he believed, and that's where he had the chance to redeem his name from the shame of the battle at Bull Run, which was really the fault of his subordinate commanders' inability to execute his plan. The nonsense with Jackson stood between McDowell and getting to Richmond.

McDowell had sent two divisions to the Valley, his First Division under Maj. General James Shields, and his Second Division under the temporary command of Brig. General James Ricketts after its former commander was transferred out West to remove him from his feud with McDowell. It was half of Shields' division that had been defeated by Jackson at Port Republic, but nonetheless McDowell was urging their return to Falmouth the day after the battle. From his headquarters in Manassas Junction he practically begged the commander of the Department of the Shenandoah, Maj. General Nathaniel Banks, to resume responsibility for the Valley. In McDowell's mind he had bailed out Banks, so Banks owed it to him to quickly relieve his men.

Banks had other ideas, though. While McDowell thought the Jackson calamity had occurred because the borders of the departments had been drawn in a way that seemed to give him some responsibility for the Valley, Banks believed it had happened because McDowell had taken away almost all of his troops, leaving him with only two brigades to defend a vitally important area. Both were right, in a way. The real problem was without an overall commander with a broad view of the situation, the individual commanders had set conflicting plans of operation into motion. McDowell could not march to reinforce McClellan while Banks also had sufficient forces to protect against a Confederate army moving up the Valley to threaten Maryland. One of the safety of Washington, the reinforcement of McClellan, or the Confederate army had to be eliminated before the others could happen.

There was a third person involved in the affair, Maj. General John Fremont, commander of the Mountain Department. Fremont had also been ordered into the Valley to bail out Banks, and his and McDowell's forces were supposed to have worked together to cut off Jackson and destroy his army. But McDowell had let Jackson get by him and followed him to Cross Keys, where he had been defeated.