Wherein he blogs about that thing that didn't happen

...........................................................................................................................................

Just a short post today on the nature of writing history.

McClellan spent October 27 reviewing troops from the division of

Fitz John Porter at Fort Corcoran [Rosslyn].

Joe Hooker was leading his division down to Budd's Ferry, opposite Evansport [Quantico], to monitor the Confederates and see if action could be taken to shut down their battery there.

Charles P. Stone was trying to get his division put back together after Ball's Bluff. And

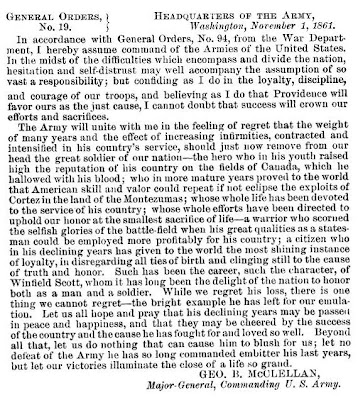

Winfield Scott was darkly waiting for the President's order into retirement, having heard the results of the

previous week's cabinet meeting.

But in the Southern army headquarters at Centreville, the concern was entirely focused on areas outside the theater. First, the army's commander, General

Joseph E. Johnston, was doing his best to ignore an order he had received on October 23 from Richmond assigning one of the new major generals he and his fellow general,

G.T. Beauregard, had fought to obtain. Maj. General

Thomas Jackson, called "Stonewall" because of his actions at Manassas, was supposed to command a division in Johnston's Second Corps. But the Confederate War Department had decided instead to send him to organize the defenses of the Shenandoah Valley in a new subordinate command to Johnston's, the District of the Valley.

Theoretically, Johnston agreed with the creation of a command specifically focused on delivering the Valley, the breadbasket of Virginia. He didn't know it, but Winfield Scott had created a semi-analogous Northern command, the District of Harper's Ferry and the Cumberland, which was to protect the critical railroad infrastructure that Confederates from the Valley could easily spill into and disrupt, cutting the capital from Ohio Its commander, Frederick Lander,

had been wounded the day following Ball's Bluff and was in Washington recuperating before heading to his new command. On October 27, men from his department under Brig. General Benjamin Kelley (a former B&O executive and a key player in McClellan's early war western Virginia successes) took aggressive action and captured the mountain city of Romney, underscoring the need for a Confederate commander.

Johnston just didn't want to lose Jackson, who, along with J.E.B. Stuart, he had been working with since April and come to rely heavily on. The trick was dragging his feet enough that the War Department would ask him to name a different commander to the critical post. Richmond, for its part, was too occupied with a different threat altogether to bother Johnston about sending Jackson (or the daily lecture about reorganizing the army to brigading state regiments together). "Sir," acting Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin

wrote Johnston, "We have received from several quarters information that the enemy intend a movement in force up the Rappahannock and that he has about 25,000 men in the fleet now concentrated at Fort Monroe for that purpose."

Benjamin continued (with a typically peculiar and prickly addendum):

This may be a feint or the information although coming from friends may have been allowed to leak out with the view of deceiving us, yet it is of sufficient importance to be sent to you. I send a private note to Colonel [Thomas] Jordan the adjutant of General Beauregard by special messenger. The note incloses [sic] a communication in cipher sent to the President from some unknown quarter and the President has an impression that Colonel Jordan has a key which will decipher it. If so, the contents will no doubt be communicated to you by General Beauregard, if of any importance. We have so many apparently reliable yet contradictory statements about the destination of this great expedition that we are much at a loss to prepare defense against it.

History recognizes the expedition as the

Port Royal Expedition and so usually leaves out the consternation it caused Joe Johnston when he thought his flank was about to be turned, and instead focuses on the planning, lead-up to, execution, and aftermath of the event as if it was one coherent whole. Union Brig. General Thomas W. Sherman and Commodore Samuel F. DuPont (of the Circle fame) were using Hampton Roads as a rendezvous for two separate forces before heading off to South Carolina together. But for those living it, the arc of the story would only be clear much later, and not fully until after the war. At the time it was a confusing event that led Benjamin to federalize the Virginia militia and accelerate the deployment of troops from as far as Georgia to Virginia, in order to protect Johnston's flank, as well ask ask Johnston to be prepared to shift large numbers of his men around.

On the next day, Benjamin wrote to Johnston,

saying, "Just heard from Norfolk that the enemy's great fleet is going

to sea, thus indicating that the threat of attack on the Rappahannock

was intended to deceive us." Even then, though, for the people living the event, where was the flotilla headed to? Thomas Jordan wrote back to Jefferson Davis directly, coolly ignoring the question about the cipher key and instead confidently let him know that his informants in Washington City indicated the attack was to be on Cape Fear, North Carolina. He was wrong, but that wouldn't be clear for another week, until the expedition appeared at Port Royal. Cape Fear wouldn't be attacked until 1864.

But while the non-story of a Union flank attack via the Rappahannock is ignored by historians short on time and space, the subject Benjamin turned his mind to next shows up in almost every account, because the story it begins goes somewhere stunning: