Porter Alexander and the phony phony war.

..........................................................................................................................

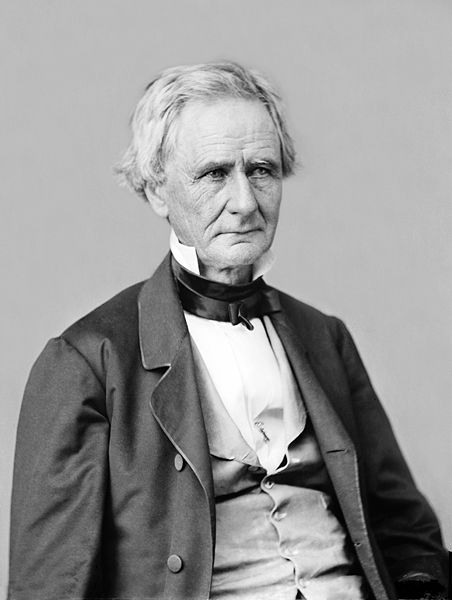

Ron at All Not So Quiet Along the Potomac has been chronicling Confederate activities and has another great post up about Joe Johnston's correspondence with new Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin on September 26 that is the beginning of the South's evacuation of the advanced line within sight of Washington. Please check it out. I offer the following post as a compliment to the narrative he is building.

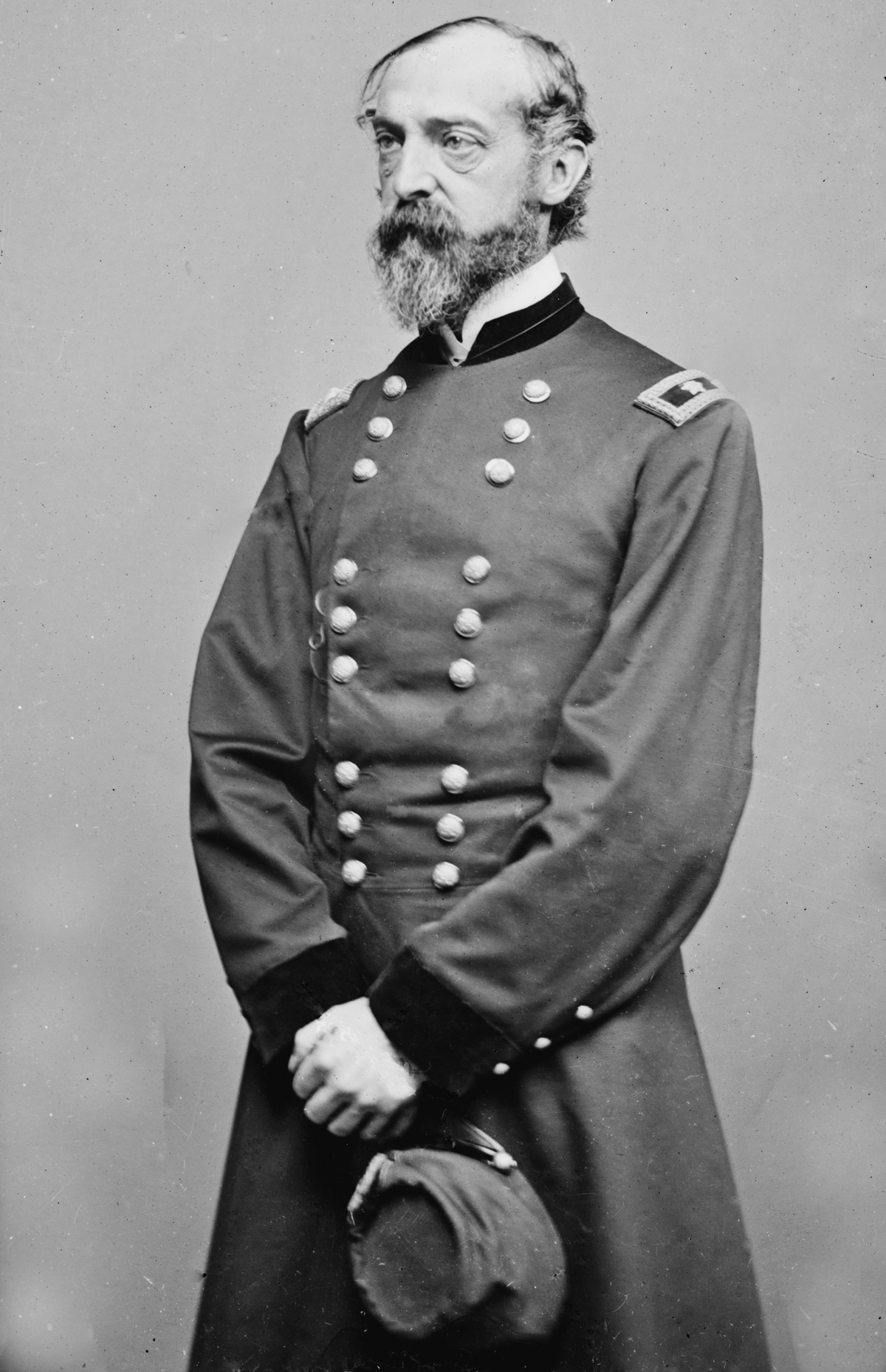

Historians tend to refer to August and September 1861 as a "phony war" or a period of quiet, but it was nothing like that for Porter Alexander and the rest of the staff officers who worked ceaselessly to prepare the two armies for their next bloody encounter. When we last saw the major, he was touring the carnage of the Manassas battlefield. His hastily trained signal corps had played as central a role in winning the battle as Thomas Jackson's stand on Henry Hill, and the head of the Confederate Army of the Potomac, G.T. Beauregard, recognized it.

The day following the battle, Beauregard asked Alexander to become his new chief of ordnance, his own having been placed in charge of a brigade of Georgians (taking the spot that would have gone to the mortally wounded Francis Bartow). A few days later, Beauregard's army was officially merged with Joe Johnston's army, and Johnston asked Alexander to continue on as the chief of ordnance, since his own had been killed on Henry Hill. Alexander eagerly agreed, and was allowed to continue to live and eat at Beauregard's headquarters, which (at least initially) was closer to Washington than Johnston's. He recounted decades later:

My duties as chief of ordnance were to keep the whole army always supplied with arms and ammunition--infantry, artillery, & cavalry. It does not sound like very much to do, but there was an infinity of detail about it & I had to organize a complete system. First I had to issue blanks to every organization in the army for each one to report what arms it had & what it needed. Then I had to organize a store house for general supplies of this kind at the R.R. station & see that each organization of the army also had a train of wagons sufficient to carry a supply for at least one battle. Then I had to have weekly returns to my office from every regiment & battery & wagon train to have my eye, as it were, on the business everywhere & see what changes were taking place & that everything was as it should be.