|

| Lincoln's note to Mansfield |

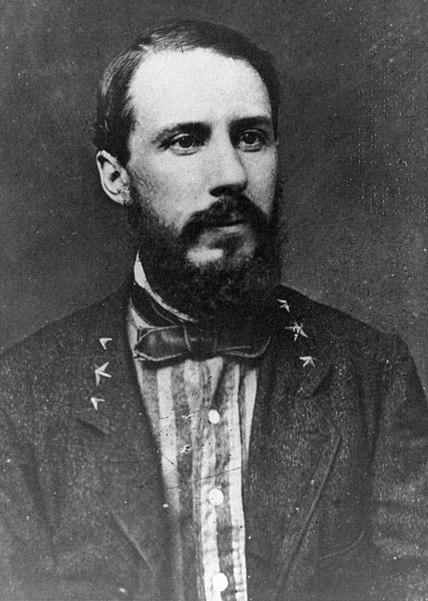

On June 19, Joe Hooker presented his

letter of introduction from Senator (and Colonel) Edward Baker of Oregon to his good friend President Abraham Lincoln. It's not recorded how long (or even if) Hooker spoke to Lincoln at the White House, but the note Lincoln scribbled survives.

The inclosed papers of Colonel Joseph Hooker speak for themselves. He desires to have command of a regiment. Ought he have it, and can it be done, and how?

Please consult General Scott, and say if he and you would like Colonel Hooker to have a command.

The note was addressed to Brigadier General

Joseph Mansfield, in command of the Department of Washington, the District of Columbia, and Maryland from Bladensburg to Fort Washington. At the outbreak of the outbreak of the war, Mansfield had been the Inspector General for the U.S. Army, but the need for experienced leaders (he had fought in Mexico with future president - and Winfield Scott arch-rival -

Zachary Taylor). Mansfield was charged with protecting 1861 Washington, D.C., which consisted of Washington City (today's Mall, the Capitol, and the White House, there wasn't much else there) and Georgetown, plus a few small villages, like Silver Spring. (Mansfield would be killed at the Battle of Antietam and would have a fort defending Friendship Heights named in his honor -- though the fort named after his cousin who died of illness in 1864,

Joseph Totten, would have a more lasting mark on the city).