Wherein the USS Pensacola attempts to run the Potomac blockade

....................................................................................................................................

|

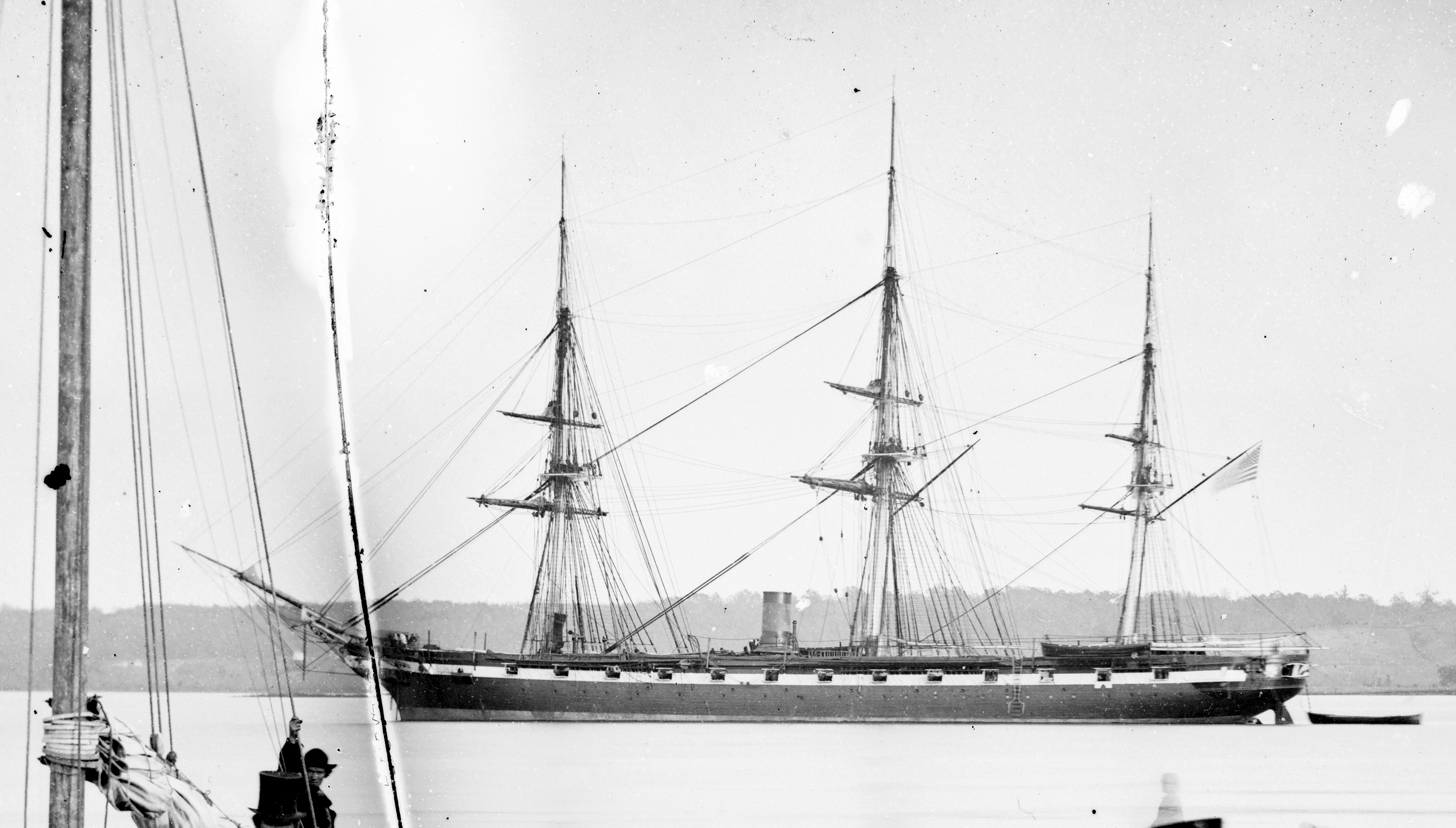

| The Pensacola moored at Alexandria in 1861 |

In the post-midnight blackness of January 12, the U.S.S. Pensacola slipped her mooring, and Captain Henry W. Morris and his sailors prepared to run the gauntlet. Morris had received his instructions four days earlier--from Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles himself--ordering him to take the 3,000 ton screw steamer to Fort Monroe in Hampton Roads, where he would then be ordered south to the Gulf of Mexico to blockade New Orleans and other ports there. "It is important that every precaution should be made to pass the Rebel batteries on the Potomac with safety to the vessel and those under your command," Welles had written Morris. "The Department relies upon your skill and upon such means as your judgment may dictate to accomplish this object."

Since November, Confederate batteries along the lower Potomac in Prince William and Stafford Counties had made traffic to the capital by river too risky. A single shot from the large guns in the right place could send any ship to the bottom with a fiery explosion. The Pensacola was one of the Navy's top ships in 1862 and was needed to stem the tide of Confederate trade in the Gulf states.

Unlike the hodge-podge of ships that made up the local Potomac Flotilla, the Pensacola had been built by the Navy for warfare, and had been completed in late 1859, only just before the war. She had been laid up in the Washington Navy Yard for two years while additional machinery was installed, and had only been fully ready in September 1861. She had then sat off Alexandria, drilling her crew, and waiting for orders, which were delayed because of the lack of any ports to which she could return for supplies and repairs in the American South. Around the turn of the year, Welles decided to utilize Key West as a base for the Gulf Squadron, since its Southern-sympathizing residents had failed to evict its garrison, and set to work building it.

The Pensacola was a natural fit. She wasn't the fastest, able to make nearly 10 knots, which was good for its day, but with her steam screws she could do it in all weather, if required. She also carried 16 9-inch Dahlgren guns, at the time a massive broadside, each of which required 16 men to operate and could fire a 90-pound shot (though they more often fired exploding shells). By comparison, this was twice the amount of weight that could be fired by the 52 cannons on the vaunted U.S.S. Constitution (only taken off active battle stations in 1855). To cap it off, the Pensacola was equipped with a singe 11-inch Dahlgren gun that pivoted, and could fire a massive 166-pound shot almost two-thirds of a mile.

To get this warship there, however, Morris was going to have to navigate down the Potomac in darkness, past the Confederate batteries. The Pensacola drew 19 feet of water, meaning she had to stay within a very narrow pathway or risk running aground and making an easy target for Confederate gunners. To prepare, Morris moved his ship to White House Point, part of the already historic Belvoir plantation of the Fairfaxes [now part of Fort Belvoir] and anchored at low tide. The first battery he had to pass was at Cockpit Point, on the bluffs above the north side of Quantico Creek. The channel ran close to the bluffs, in those days, making it necessary to slip by after the moon had set, but Mattawoman Creek, which emptied into the Potomac on the Maryland side just north of Cockpit Point, dumped (and still does) massive amounts of silt into the river, creating dangerous mud flats that could ruin Morris's ship.

|

| Lt. R.H. Wyman |

Morris and Wyman hatched a scheme, which the former explained to his superiors in the Navy Department on the afternoon of January 11:

I have communicated with Lieutenant Commanding R.H. Wyman of the Potomac Flotilla, and made arrangements with him to anchor some of his vessels at the buoys on the Mattawoman mud, with colored lights up, to enable me to steer by, and also for others to attack the batteries whilst I am passing them, to distract attention from me.At 1:00 am, the Pensacola slipped her moorings and began traveling down the Potomac while the tide was still high, Wyman's smaller flotilla steamers accompanying them. They made it over the mud flats with no problem, and steamed as quietly as possible for Cockpit Point. Morris had arranged a signal with Wyman, whereby if the Pensacola fired off a shot the Flotilla would take it as a signal to open fire, drawing the Confederate batteries to itself while Morris's ship silently sped down river. Wyman was preparing to sacrifice his own ships and the lives in them to get the Pensacola to the Gulf.

Morris and Wyman had timed it nearly exactly right, and reached Cockpit Point just after the moon set at 4:30 pm. The sky, Morris recorded, "was slightly obscured by clouds, so that after the moon had set... the darkness made us indistinct to them, whilst it was not too dark for us to see the shores of the river and enable us to steer by them and keep to the channel."

In direct command of the Confederate batteries at both Cockpit Point and Evansport was Brig. General Samuel G. French, a New Jersey native who had relocated to Mississippi to run a plantation after ending his career with the U.S. Army because of a severe wound he had received at Buena Vista. French, through spies and friendly locals, had known that the Pensacola was stuck at Alexandria, and that the Union would want to move her to a more useful location eventually, and been waiting for his chance to take a shot at her.

At 9 pm [on January 11], I saw a light in an unusual place and sent a courier down to the battery to report to Captain Peatross to observe unusual vigilance and have everything ready in case the Pensacola should attempt to ran past. These instructions were given, and the men in some of the companies removed none of their clothing; these instructions were also given to the officer of the day, the officer of the guard, and the guard in the battery.

French spent the night restless, trying to anticipate Morris's move: "Between 11 and 12 o'clock at night, Captain Collins and I went with our glasses and made a long and careful survey of the river, up and down, but could discern nothing."

French spent the night restless, trying to anticipate Morris's move: "Between 11 and 12 o'clock at night, Captain Collins and I went with our glasses and made a long and careful survey of the river, up and down, but could discern nothing."Morris and Wyman guided their ships past Cockpit Point, silently, but to their surprise no Confederates opened fire. Then, some time between 4:00 and 5:00, the Pensacola was discovered. A sentinel on the south side of Quantico Creek attached to the Evansport batteries spotted her and rushed to the corporal in charge of his detachment. Wanting to make sure that it was the real thing, the corporal peered into the darkness intently, squinting to make out darker shapes on the dark water. And then there she was, on the water, already past Battery No. 1, the northernmost section of guns in the Evansport cluster.

The corporal rushed to awaken the gunners and send a message to French. Battery No. 2 opened fire, along with some of the other gun collections, but the Pensacola was already out of the field of fire of Battery No. 1. Hearing their comrades on the south bank open fire, the Cockpit Point batteries opened up too, raining a collection of shot and shells around the Union ships. "From two guns, the new guns, and Battery No. 2," French reported (somewhat confusingly), "a fire was opened and it is certain she was struck several times."

On the Pensacola, things looked a bit different. Morris stayed cool and refrained from answering the fire. "I did not return the enemy's fire, as it would only have exposed my position to them without enabling me to do them any damage, on account of the dark of the night." He estimated that the Confederates only got off about 15 shots, an estimation shared by his Army counterpart watching the action from the Maryland shore.

The Pensacola passed the batteries about 5 o'clock this morning, unharmed," Brig. General Joe Hooker would write much later in the afternoon of January 12. "Fifteen or twenty shots were fired by the rebels as she descended the river, when she must have been lost sight of from that shore. From the Maryland shore, an indefinable dark object was all that my pickets could see of her."

Wyman held his fire too, and by the first hints of daylight at 6:00 am, the Flotilla and the Pensacola were well past the batteries. French fumed, blaming the Cockpit Point lookouts for failing to spot her, and his own men for their slow response: "Had that battery seen her pass it and fired sooner, our men could have been at their guns in time; or had the corporal at once summoned the crews, many more shots could have been fired."

Hooker was less sanguine, irritably reiterating a point he frequently made to McClellan's chief of staff:

It is deserving of remark in the history of these heavy batteries, that during my sojourn here the enemy have discharged them not less than 5,000 times, and with the exception of the single shot which struck one of the vessels of the flotilla a few days since, while she was engaged in exchanging shots with them, not a vessel has been damaged in navigating the river nor the skin of a person broken on our shore.Morris was more generous to his opponents, describing their fire as "very good, but aimed too high."

Though the Pensacola was safely anchored at Sandy Point, the ordeal wasn't over. For one thing, no one in Washington had any way to know whether the ship was safe, and Gideon Welles began asking the commander of the Navy Yard, John Dahlgren (inventor of the gun), to send another vessel to try to spot the Pensacola, or at least its burning wreckage. For another, Wyman had to bring his ships back through the gauntlet (already well underway by the time Morris anchored). Hopping mad, French wasn't going to let anything pass through his field of fire.

Hooker drolly observed the activity of the remainder of the day:

Later in the day, the rebels were very active with their heavy guns, and blazed away at almost every object that presented itself, whether within the range of their guns or not. To me it seemed like an ebullition of anger on the escape of the Pensacola, for they had evidently made unusual preparation to receive her. Their accumulation of ammunition was afterwards expended on objects of little or no importance, and without result.By the afternoon, the Flotilla was back at its usual station without damage or loss of life, Welles and the Navy Department staff were congratulating each other, and French was blasting away uselessly at nothing. By January 14, Morris and the Pensacola would be in Hampton Roads, provisioning for the journey to Key West, and French would finally begin writing his defensive official report.

No comments:

Post a Comment