Wherein Lincoln almost loses his head to the French

..................................................................................................................................

The New York Times ran the story on April 27, a full day before the local Evening Star.

The President's visit to the French frigate Gassandi this afternoon was an event of historical importance; it was the first time a President of the United States ever went on board of a foreign vessel of-war that ever came to Washington.On Saturday, April 26, 1862, Lincoln had done a bit of diplomatic relations, inextricably tangled with his natural curiosity. Things had been tense with the French since the Trent affair, when the Emperor Napoleon III had sided with the British in demanding the return of Confederate diplomats. The French had declared themselves neutral in the American Civil War, a step for which Secretary of State Seward had lambasted them. But Seward's warm welcome of the kinsmen of the exiled King Louis-Philippe, the Prince de Joinville and his two nephews (both of whom were on the Peninsula serving as aides-de-camp to George McClellan), had equally infuriated the French.

And now, there was a multi-national force of British, French, and Spanish soldiers in Mexico to force the Juarez government to repay its debts, despite Seward's futile protests about the Monroe Doctrine. With the rebellion of the Southern states there was no credible threat he could make to keep the Europeans out of the Western Hemisphere. News hadn't made it to Washington yet, but the British and Spanish had realized the French had even greater ambitions in Mexico and begun withdrawing their forces.

The French Ambassador, Henri Mercier, had called on the President a few days earlier to invite him to the Gassandi for an official visit. The ship had just returned from Hampton Roads, where it had been moored when the CSS Virginia had dueled the USS Monitor, its crew having received front row seats for the historic battle. Lincoln was ravenous for news about the battle and Seward thought he recognized an olive branch opportunity, so the two were off, along with Seward's son Frederick.

At the Washington Navy Yard they were met by Commander John Dahlgren, commandant of the yard (and as such called "captain" as a courtesy). The Times again:

The President was attended at the landing by a full guard of marines and the band, who played the National airs, Capt. Dahlgren and the other officers of the yard receiving him in a body.Dahlgren manned the tiller of the barge he had ordered ready, and Lincoln and the Sewards took a seat next to him in the sternsheets. As they struck out into the Eastern Branch [Anacostia] and approached the Gassandi, an American flag was unfurled on the main mast. The French sailors had lined the decks and the yardarms in a ceremonial honor reserved for heads of state.

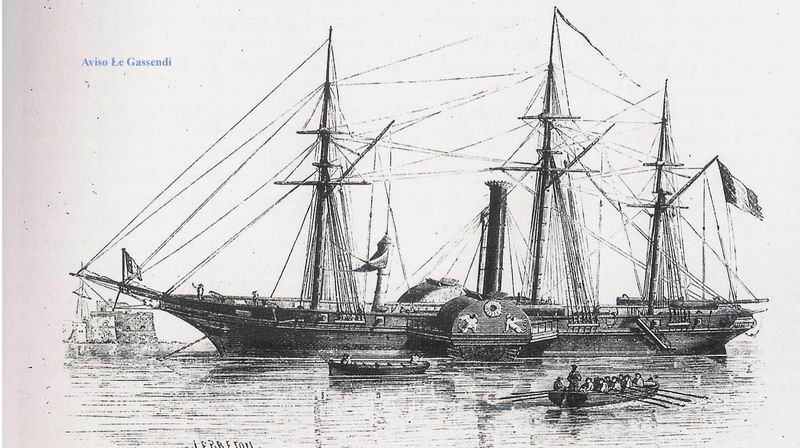

Though the Times and other American papers had described the ship as a frigate, she was actually a smaller ship, known as an "aviso". With three masts and a paddle wheel, she was still smaller than the Cumberland, the American frigate that she had witnessed the Virginia shredding in Hampton Roads. Launched in 1840, the Gassandi had seen its first action in Tangiers, Morocco, as part of a squadron bombarding the native garrison under none other than the Prince de Joinville (pre-exile) that received a snooty write-up in an early edition of the Economist. She would only have three more years of service, before the revolution of the ironclads and the disappointment of her own design flaws ended her career.

Dahlgren hove-to next to the aviso, and Lincoln was helped on board. As the Times reported:

He was received with all the honors paid to a crowned bead, being the same as usually shown to the Emperor. The yards were manned, the ship was dressed with flags, and the American National ensign floated at the main, and the French at the fore, mizzen and peak. The National salute was fired on his arrival, and again on his departure. Admiral Reynoud received him at the foot of the ladder, and the seamen seven times shouted "Vive le President!" on his arriving and leaving. Capt. [Jules] Gaudier entertained him hospitably in his cabin, and presented the officers of the ship.According to Frederick Seward, Gaudier's entertainment was hospitable indeed:

Champagne and a brief conversation in the captain's cabin came next; then a walk up and down her decks to look at her armament and equipment. Though the surroundings were all new to Mr. Lincoln, he bore himself with his usual quiet, homely, unpretentious dignity on such occasions, and chatted affably with some of the officers who spoke English.

As they left, a second twenty-one gun salute began from the Frenchmen. But the adventure wasn't over yet for the official party. Frederick Seward continued:

As Mr. Lincoln took his seat in the stern he said: 'Suppose we row around her bows. I should like to look at her build and rig from that direction.' Captain Dahlgren of course shifted his helm accordingly. The French officers doubtless had not heard or understood the President's remark, and supposed were pulling off astern in the ordinary way.

We had hardly reached her bow, when, on looking up, I saw the officer of the deck pacing the bridge, watch in hand and counting off the seconds, 'Un, deux, trois,' and then immediately followed the flash and deafening roar of a cannon, apparently just over our heads. Another followed, then another and another in rapid succession. We were enveloped in smoke and literally "under fire" from the frigate's broadside. Captain Dalhgren sprang to his feet, his face aflame with indignation, as he shouted: 'Pull like the devil, boys! Pull like hell!" They obeyed with a will, and a few sturdy strokes took us out of danger.

The younger Seward knew enough to know that in a salute the guns were not loaded with shot, only powder. And besides, the barge had been almost directly under them, so if they had been they would have fired over their heads. "Yes," Dahlgren quietly answered his question through gritted teeth, "but to think of exposing the President to the danger of having his head taken off by a wad!"

He was still confused, so when they reached the shore and Lincoln was well out of ear shot, Dahlgren went into more details for the young man.

I did not know, until he explained, that the wadding blown to pieces by the explosion sometimes commences dropping fragments soon after leaving the gun. Whether Mr. Lincoln realized the danger or not, I never knew. He sat impassively through it, and made no reference to it afterwards.

The photo is a rare find! I've been looking for a photo of the Gassandi for a while now and I was very pleased to find this. Could you tell me what the source is (it isn't in the NYTimes article) or where I might find the original? Thanks-

ReplyDelete-Andreea