Wherein sharp words find their logical place in the Senate

.................................................................................................................................

In the wake of the Northern loss on the hills overlooking Bull Run all the fears of March returned to Washington. The rout of Irvin McDowell's army had galvanized the South, in the same way the surrender of Fort Sumter had months before. Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina had all waited until after Lincoln's April 17 call for volunteers to secure Federal property before seceding, but the fall of Sumter on April 12 couldn't have been overlooked when they decided to leave the Union. Another Confederate victory in northern Virginia could be the push Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, or Missouri needed to declare for Richmond.

The Lincoln Administration had been aggressively attempting to make sure this did not happen. In Missouri, where the state's secessionist governor and part of the state militia had taken up arms against the Federal government claiming the state had left the Union already (the legislature voted to do so, but without a proper quorum), there was an army of militia under Nathan Lyon and John C. Fremont marching to quash the insurrection. In Maryland, soon-to-be Major General (USV) Nathaniel P. Banks had been using military might to detain suspected secessionists (especially in Baltimore) without trial since May, and his successor when he took over at Harper's Ferry, John Dix, was actively searching for secessionists too.

If Maryland exploded into violence like Missouri had, what would be the authorities of the Federal forces? After all, the governor of Missouri was leading the rebels there, what would happen if Fremont forcibly detained him and put him on trial if the state courts recognized the Confederacy? For that matter, what about the mountains of western Virginia and the area around Fort Monroe in Virginia under the control of Federal armies?

On August 1, the Senate took up a bill to allow military leaders to supplant civil authorities in states deemed to be in insurrection. Senator Lyman Trumbull (R-IL), the Chairman of the Judiciary Committee, was the bill's sponsor, and it would allow the President to declare an area governed by a military command in "insurrection" and thereby allow martial law and military trials in place of the usual civilian trials (with the stipulation that they should only be used if civil authorities were unable or unwilling to execute laws). It effectively allowed the President and the Army to treat parts of the United States as if they were foreign countries with which it was at war, without recognizing the seceded states as foreign countries.

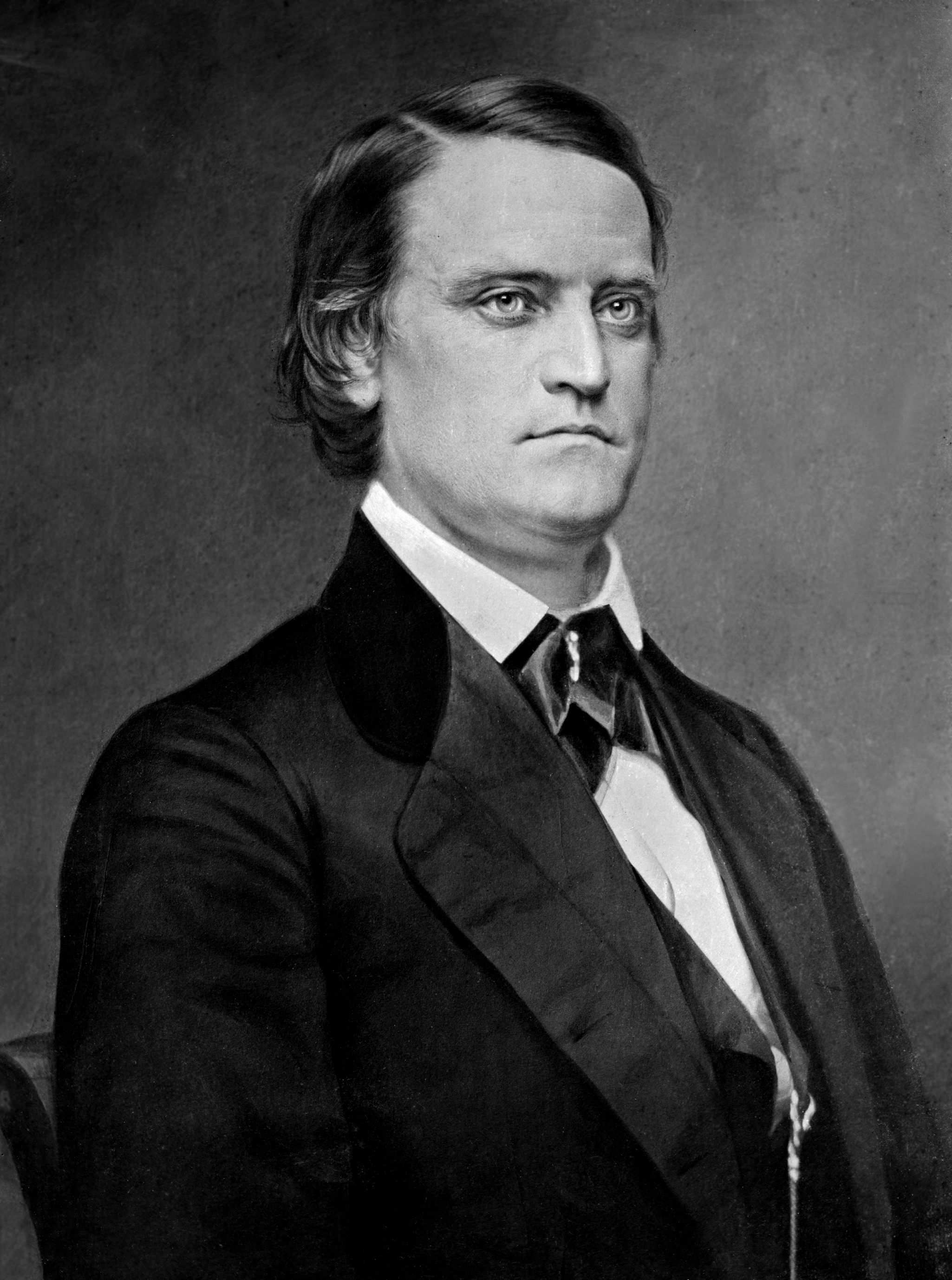

|

| John C. Breckinridge (Matthew Brady) |

But Breckinridge was feeling particularly feisty during debate on the first day of August. After listening to Republicans argue amongst themselves whether to work on the bill immediately or to wait until December, he reappeared on the Floor to crow, "Appalled by the extent of [the bill], and embarrassed by what they see before them and around them, the Senators who are themselves the most vehement on urging this course of events, are beginning to quarrel amongst themselves as to the precise way in which to regulate it."

He followed with a savage critique of Lincoln for disregard of the Constitution, going section by section through the bill.

Well might the Senator from Delaware [Willard Saulsbury (D)] say that this bill contains provisions conferring authority which never was exercised in the worst days of Rome, by the worst of her dictators. I have wondered why this bill was introduced. I have sometimes thought that possibly it was introduced for the purpose of preventing the expression of that reaction which is now evidently going on in the public mind against these procedures so fatal to constitutional liberty.Among his predicted tyrannies: "The Army may be thus used, perhaps, to collect the enormous direct taxes [i.e. income tax] for which preparation is now being made by Congress."

I am quite aware that all I say is received with a sneer of incredulity by the gentlemen who represent the far Northeast; but let the future determine who was right and who was wrong. We are making our record here; I, my humble one, amid the sneers and aversion of nearly all who surround me, giving my votes, and uttering my utterances according to my convictions, with but few approving voices, and surrounded by scowls. The time will soon come, Senators, when history will put her final seal upon these proceedings, and if my name shall be recorded there, going along with yours as an actor in these scenes, I am willing to abide, fearlessly, her final judgment.Senator Edward Baker (R-OR) had had enough at that point. "I have listened for some little time past to what he has said with an earnest desire to apprehend the point of his objection...and now... I propose... to ask him if he will be kind enough to tell me what single particular provision there is... in violation of the Constitution... ?"

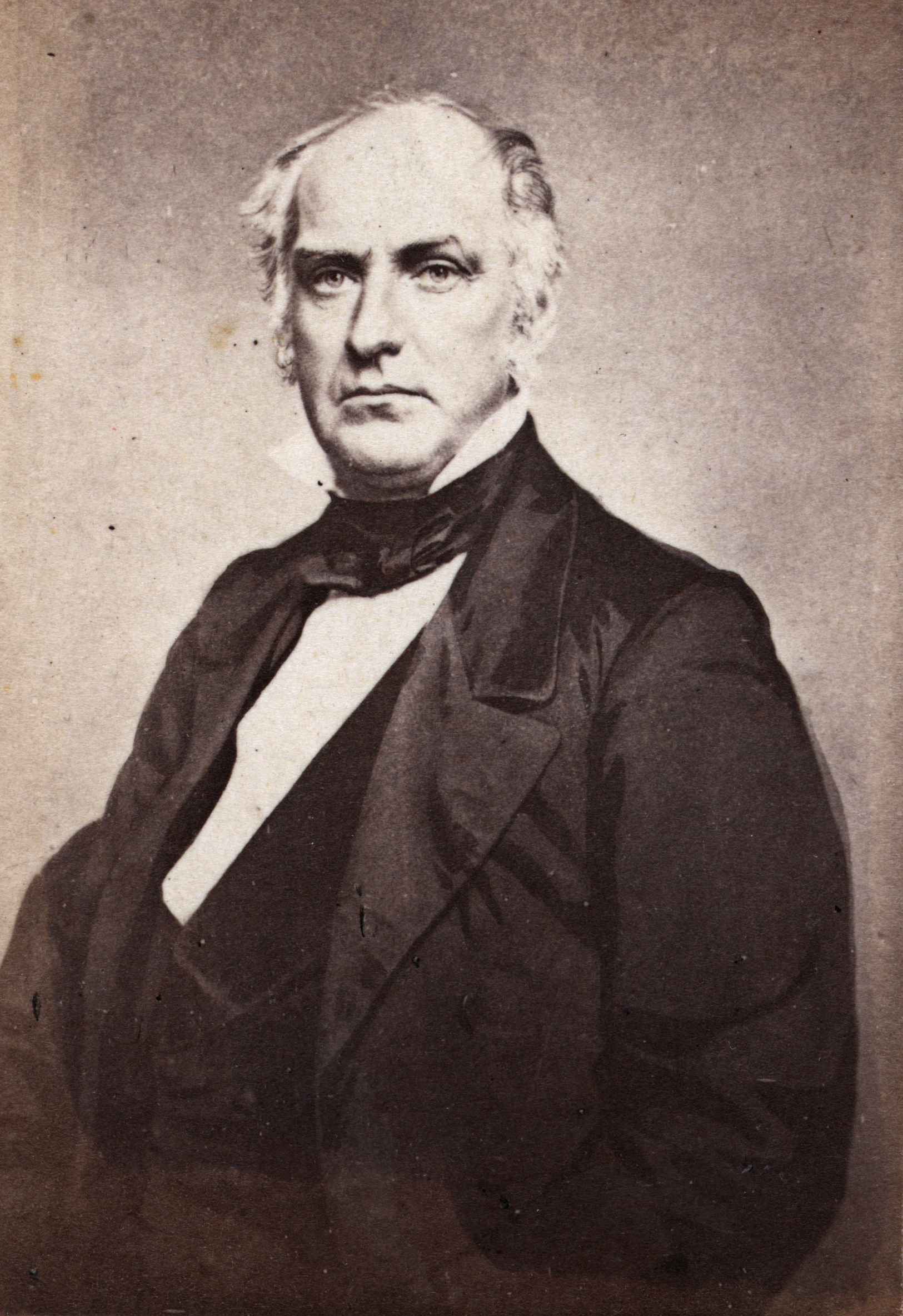

|

| Edward D. Baker |

BAKER: Pick out that one which is in your judgment most clearly so.

BRECKINRIDGE: They are all, in my opinion, so equally atrocious that I dislike to discriminate...

BAKER: Let me try then... Is it unconstitutional to give power to the President to declare a portion of the territory of the United States in a state of insurrection?...

BRECKINRIDGE: ...The Senator from Oregon is a very adroit debater, and he discovers, of course, the great advantage he would have if I were to allow him, occupying the floor, to ask me a series of questions, and then have his own criticisms made on them. When he has closed his speech, I may make some reply...

Baker then launched into a spirited defense of the bill, following Breckenridge's example and going line-by-line, but emphasizing instead the threat to the nation by the armed rebellion.

There is a state of public war; none the less war because it is urged from the other side; not the less war because it is unjust; not the less war because it is insurrection and rebellion... Shall we carry that war on? Is it his duty as Senator to carry it on?...

Will the honorable Senator tell me it is our duty to stay here within fifteen miles of the enemy seeking to advance upon us every hour, and talk about nice questions of constitutional construction as to whether it is a war or merely insurrection? No sir, it is our duty to advance, if we can; to suppress insurrection; to put down rebellion; to dissipate the rising; to scatter the enemy; and when we have done so, to preserve in the terms of the bill, the liberty, lives, and property of the people of the country, by just and fair police regulation.Baker insisted that he too was sensitive to the need to protect rights, before going in for the kill.

I agree that we ought to do all we can to limit, to restrain, to fetter the abuse of military power. Bayonets are at best illogical arguments... But, sir... you can not carry in the rear of your army your courts... and somebody must enforce police regulations in a conquered or occupied district. I ask the Senator from Kentucky again respectfully, is that unconstitutional; or if in the nature of war it must exist, even if there be no law passed by us to allow it, is it unconstitutional to regulate it...

I would ask him, what you would have us do now... Are we to stop and talk about an uprising sentiment against the war in the North? Are we to predict evil and retire from what we predict?... Will the Senator yield to rebellion? Will he shrink from armed insurrection?... Should we send a flag of truce? What would he have? Or would he conduct this war so feebly, that the whole world would smile at us in derision? What would he have? These speeches of his, sown broadcast over the land, what clear distinct meaning have they? Are they not intended for disorganization in our very midst? Are they not intended to dull our weapons? Are they not intended to destroy our zeal? Are they not intended to animate our enemies? Sir, are they not words of brilliant, polished treason, even in the very Capitol of the Confederacy?The gallery broke into rapturous applause as Baker thundered his denunciation of Breckinridge's statements. When order was restored, he concluded with a statement that the indulgence of Breckinridge was proof there was no tyranny afoot in Washington, and how that freedom guaranteed by the Constitution needed to be preserved.

If we have the country, the whole country, the Union, the Constitution, free government-- with these there will return all the blessings of well--ordered civilization; the path of the country will be a career of greatness and of glory such as, in the olden times, our fathers saw in the dim visions of years yet to come, and such as would have ours now to-day, if it had not been for the treason for which the Senator too often seeks to apologize.The debate wasn't over, but Baker had won. Breckinridge's answer was hot and pedantic, revisiting his earlier points and nit-picking at Baker's. To answer what he would have them do, he stated clearly "I would have us stop the war," insisting that no "fratricidal, devastating, horrible contest" could restore liberty. But Breckinridge had lost the momentum, and the motion to set aside the bill failed as other Senators came to the Floor to speak in favor of it.

But in the end, it turned out to be the nominations of generals the day before that killed the insurrection bill's prospects. Twenty-one Senators - including both Breckinridge and Baker - voted to move to executive business rather than continuing to debate the bill, and it was put off until December after all.

No comments:

Post a Comment