Wherein we go afloat and end up aloft

...........................................................................................................................................

|

| Map of Rebel batteries (left) on the Potomac River, beginning of November |

Three schooners passed up the river under a six knot breeze without the slightest injury, although thirty-seven heavy guns were discharged to dispute their passage. The crews seemed to entertain a just appreciation of the batteries, for they sailed along with as much unconcern as they would to enter New York Harbor. They do fire wretchedly. Whether it is owing to the projectiles or to the guns I am not informed. Several of the pieces are rifled, but they seem to throw more wildly if possible than the smooth bores. From what was witnessed to day and on previous occasions, I am forced to the conclusion that the rebel batteries in this vicinity should not be a terror to any one.Despite Hooker's conclusions, he had been sent there two weeks earlier in order to work with the U.S. Navy's Potomac Flotilla to eliminate the potential threat that the batteries caused to Union shipping. At the order of the Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, river traffic had been reduced to a fraction of the usual shipping required to sustain the capital, and almost all supplies were coming down the B&O Railroad from Confederate-sympathizing Baltimore.

Hooker knew a good thing when he had it, though, and was content to ride out the winter with his division over a day's march from Washington and therefore from George McClellan, his staff, and anyone else who might outrank him. Not nearly as content with his situation was Commander Thomas Tingey Craven, the head of the Potomac Flotilla. As early as October 23, Craven had declared the mission of the flotilla to control the river a lost cause and suggested removing the guns from his ships and setting up batteries on the Maryland side that could exchange fire with the Confederates (his plan was partially put into action, the guns from the Pensacola had been used by Hooker to establish his one operating battery at Budd's Ferry).

"Feeling that my position here in command of the flotilla can be of no further benefit," Craven wrote Welles, "I most respectfully request to be detached from the command and appointed to some seagoing vessel."

Unlike Hooker, who was attached to an army increasingly unlikely to fight a battle before March, Craven was missing out on major naval operations at Port Royal and Hatteras Island, as well as chasing down Confederate blockade-runners. The U.S. Navy of 1861 was even more ad hoc than the U.S. Army. At the beginning of 1860, the only 42 ships comprised the entire fleet, and most of them were laid up for repairs. As States began seceding, the general-in-chief, Winfield Scott, convinced the Buchanan Administration that the Navy could end the secession crisis without bloodshed or political repercussions, and by January 1 the Navy had grown to 82 vessels, mostly through acquisition of ships from other parts of the government and purchase of merchant ships. The Lincoln Administration's focus on a blockade as a war strategy meant a massive building program, and by January 1, 1862, it would have 213 ships, and by January 1, 1865, it would have 569.

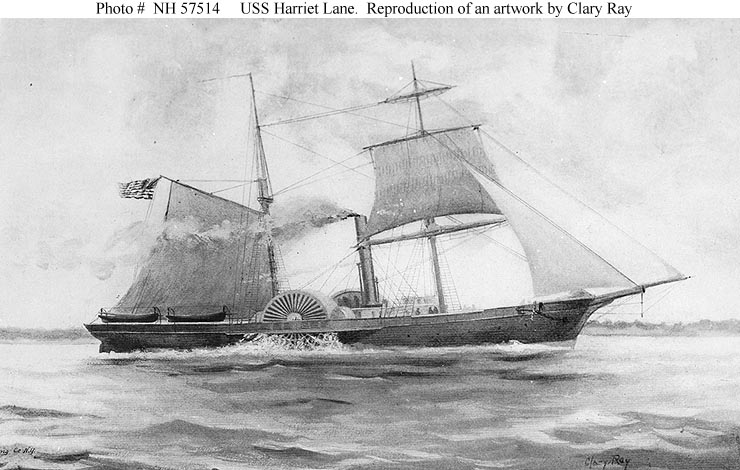

Craven wanted to be out there with that expanding Navy on real warships, instead of cooped up in the Potomac next to dangerous but poorly operated batteries, sailing converted merchant ships. His own flagship, the U.S.S. Harriet Lane (named for President Buchanan's niece and also the bachelor president's First Lady), had at least started the war as a revenue cutter meant to catch smugglers (the U.S. Revenue Cutter service later merged with a national rescue service to become the Coast Guard). But most of the ships in Craven's small command had been bulky merchant ships. Typical was the U.S.S. Ice Boat, a miserable steamer leased from the City of Philadelphia that leaked water like a sieve.

But Craven wasn't the only Navy officer in the area displeased with his assignment. At the Washington Navy Yard on the Eastern Branch [Anacostia], Commander John Dahlgren was casting about for something to get him noticed. The Navy Yard had been started in 1799 by the first Secretary of the Navy, Benjamin Stoddert (grandfather of Confederate general from Fauquier County, Dick Ewell) to build ships, and it became the largest shipbuilding facility owned by the Navy under its first commandant, Thomas Tingey (coincidentally, Craven's grandfather and namesake). The burning of the Yard by the British in 1814 coincided with the silting of the Eastern Branch, and the Navy converted the Yard to its premier facility for ordnance and naval technology (a role it would retain until 1964, in the process poisoning the ground around it so that Nationals Park needs a two-foot rubber tub between the grass and the native soil).

Dahlgren had ended up commanding this crucial post by accident. The Baltimore-born commandant of the Yard had left suddenly to join the Confederacy, where he was spending November helping them organize their navy (and would spend the spring commanding the C.S.S. Virginia). Dahlgren was not senior enough for such an important post. The U.S. Navy of 1861 had only four commissioned grades, though distinctions had already been informally created within them.

In 1826 Dahlgren, the son of the Swedish consul to Philadelphia, had started his journey up the ladder when at age 16 he became a midshipman. As a midshipman he was considered an officer and so had to be saluted by the sailors, was given the title "mister", and commanded a watch and battle station. But he was also supposed to learn from the other officers the art of commanding at sea (when the U.S. Naval Academy opened at Annapolis in 1845, much of the instruction of midshipmen would be transferred to the classroom). He also berthed midship, halfway between the crew (towards the bow) and the officers (towards the stern). Dahlgren took two cruises before he proved himself a capable seaman and was advanced to the next grade, "Passed Midshipman" in 1832 (it would become "Ensign" in 1862).

As a passed midshipman he was still expected to be honing his command skills, but was expected to require very little further instruction. His interest in math and science had found him a home in the U.S. Coast Survey, an ongoing effort to create accurate charts of all of the nation's coastal waters. While there in 1837 he was promoted to lieutenant. (A tangent: at the time, Americans pronounced the word "looftenant", as inherited from the English pronunciation "luftenant". The generation that fought the American Civil War turned the American version to today's "lootenant", perhaps because of the large influx of less aristocratic and accented men in both the army and the navy pronouncing the grade. The British, meanwhile, continued to evolve themselves to reach today's pronunciation of "leftenant", which they indignantly insist is the only sensible way to say it.)

As a lieutenant, Dahlgren eventually became an officer on the U.S.S. Cumberland, where he and several other lieutenants took responsibility for helping the captain run the ship and training the midshipmen. Had Dahlgren showed more aptitude at command at sea, he might have been able to command his own vessel as a lieutenant. In Craven's Potomac Flotilla in November 1861, A.D. Harrell was the skipper of the U.S.S. Union watching Aquia Creek, and was differentiated from a lieutenant operating under the eye of a captain by the informal title "lieutenant commanding". In 1862, the U.S. Navy would go ahead create an official separate grade called "Lieutenant Commander."

Also capable of commanding vessels was the "Master", but this was not a commissioned officer and not a grade that Dahlgren would have been eligible for. The U.S. Navy had continued the Royal Navy's tradition of recognizing skilled enlisted men and giving them "warrants", slips of paper from the Admiralty that allowed them special rights and the ability to command non-officers. Both Navy's recognized certain expert seamen as "sailing masters" and treated them like officers higher than everyone but the captain of the ship by custom, even though they held no commission. By the mid-19th Century, the U.S. Navy even let them command ships by themselves.

By practice, everyone who commanded a ship including a master was called "captain" by their crew, regardless of whether they held that rank. Thus, Commander Thomas Craven is frequently called "Captain Craven" in reports, despite not being that senior. Captain was the highest level that could be reached in the U.S. Navy in 1861, but captains that were also in charge of multiple ships, like Craven, were sometimes called "commodore" or "flag officer", even though neither of those would become real grades until 1862.

That was all beyond Dahlgren's concern in 1861, though. He had been made a "Commander" in 1855, but by that point it had become clear to everyone but Dahlgren himself that his talent did not lie at sea. He had been stationed at the Navy Yard and developed a new gun, a sort of ship howitzer, that had revolutionized warfare at sea. Dahlgren, who was a shameless self-promoter, tried to use its success to land command of his own vessel, but instead it just persuaded President Lincoln to hand over the Navy Yard to him.

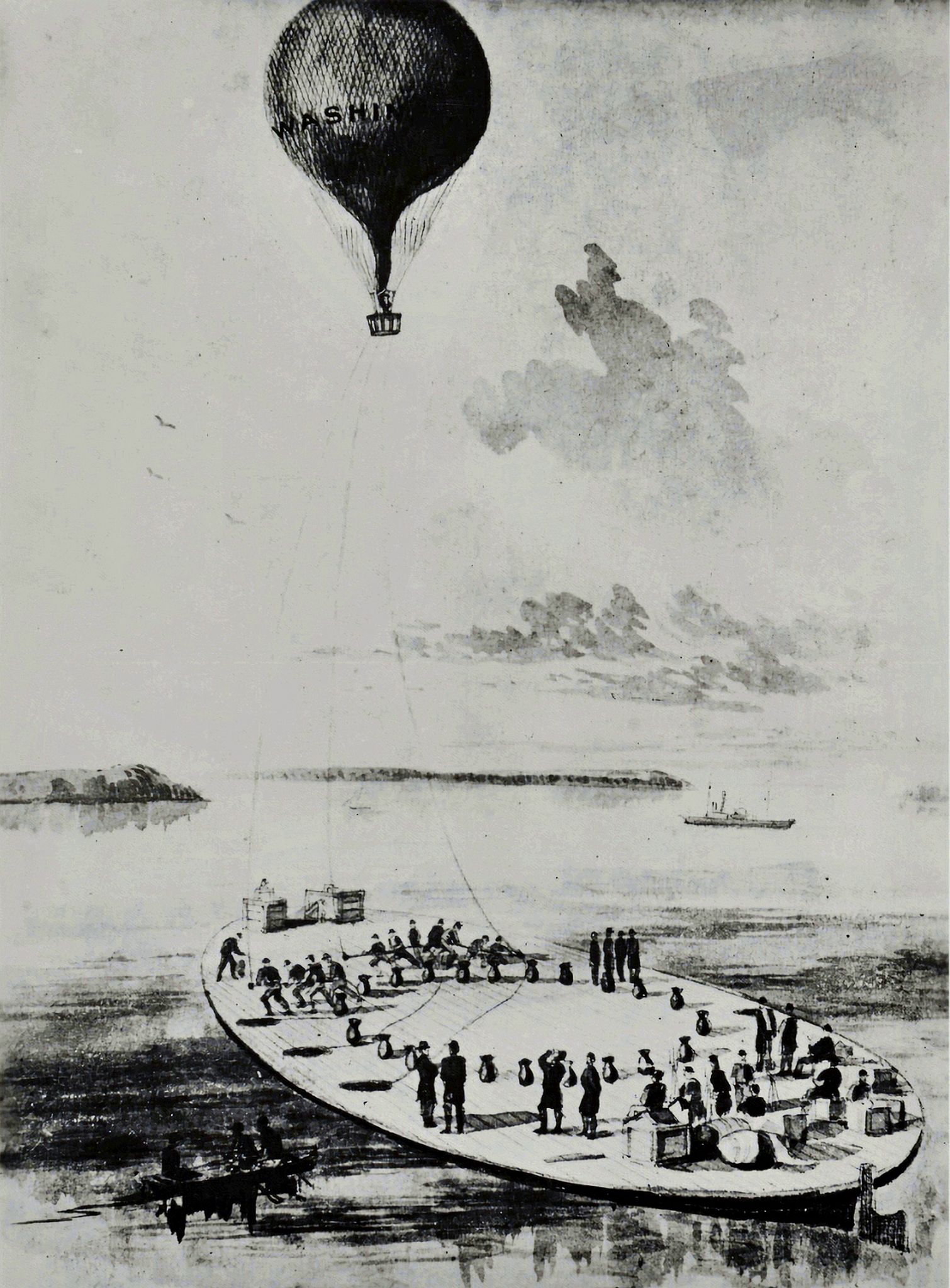

While stewing through Fall 1861 on ways to get the sort of attention that would get him involved in the fleet, Dahlgren was sent an order by Gideon Welles to assist Thaddeus Lowe with a project. Lowe was working overtime to sell balloons to the War Department, but an August experiment by his top rival, John LaMountain, convinced him to try to sell balloons to the Navy Department. LaMountain had tied a balloon to the stern of a ship and observed Confederate batteries. Lowe thought he could one-up him by creating an actual balloon-bearing ship that could go anywhere and provide observations, so he convinced Gideon Welles to buy him a coal barge dubbed the U.S.S. George Washington Parke Custis (named after Robert E. Lee's father-in-law and builder of Arlington House).

|

| Lowe ascending over the Custis |

On November 10, Dahlgren loaned them the U.S.S. Coeur de Lion to tow the Custis down the Potomac, with Lowe and Sickles aboard and planning to launch their balloon the next day. "The balloon was inflated about 8 o'clock p.m.," Hooker reported with unusual terseness in his report of November 11, "but whether an ascension was made or not I am not advised. If the elements should favor she will to-morrow."

In fact, Lowe had made an ascension just off of Cockpit Point, and taken Sickles up with him. "We had a fine view of the enemy camp fires during the evening and saw the rebels constructing batteries at Freestone Point," Lowe would write up in one of his typically self-promoting reports. While Hooker had remained less than impressed, both Dahlgren and Sickles were sold and had high hopes for the Custis and balloons on the Lower Potomac.

Print Sources:

- Eicher & Eicher, 74-83.

No comments:

Post a Comment