In which Winfield Scott is at last deposed

........................................................................................................................................

On November 1, the long war that had burned since the end of July at last came to a close. Maj. General George Brinton McClellan became the U.S. Army's general-in-chief. McClellan and the army's outgoing general-in-chief, Bvt. Lt. General Winfield Scott had been at each others' throats for months. Back during the summer Scott had asked the President to put him on the retired list to try to force him to reign in the ambitious young McClellan, who was circumventing Scott to talk strategy with Cabinet members directly and who refused to give Scott any details about his army. Lincoln had ignored Scott's retirement gambit after only a minor rebuke of McClellan, and the campaign had simmered. Then Scott had tried to catch McClellan disobeying a lawful order, a scheme in which the younger man happily obliged, but Secretary of War Simon Cameron had done nothing to punish him. So Scott had renewed his request to be placed on the retired list and on October 31, the president had finally complied. By having his name added to the retired list, Scott would receive a full pension, but be ineligible to command troops any longer. Characteristically, Lincoln informed Scott that his suggestion was accepted gently, telling him he would still call on him for advice, but not too often so he could properly enjoy his retirement.

Before the President had even issued the order, word of the intended action had already leaked out to McClellan. On October 30, he had passed on some of the capital's gossip to his wife, Mary Ellen:

You may have heard from the papers etc of the small row that is going on just now between Genl Scott & myself--in which the vox populi is coming out strongly on my side. The affair had got among the soldiers, & I hear that offs & men all declare that they will fight under no one but "our George" as the scamps have taken it into their heads to call me. I ought to take good care of these men, for I believe they love me from the bottom of their hearts. I can see it in their faces when I pass among them. I presume the Scott war will culminate this week--& as it is now very clear that the people will not permit me to be passed over it seems easy to predict the result.By the night of October 31, McClellan knew of Scott's retirement and was hard at work on a memorandum that Secretary of War Simon Cameron had recommended he write about the state of operations for the Army of the Potomac. He told Mary Ellen on that day that he was "at work all day nearly on a letter to the Secy of War in regard to future military operations." McClellan seems never to have seriously considered that in elevating him to the position of top general for the U.S. Army the President might have asked him to turn over command of his own army to someone else. Since there's no record of Lincoln or the Cabinet discussing the possibility (or none your intrepid blogger can find), it's possible that McClellan had been verbally assured already that he would command both the Union war effort and the Army of the Potomac.

Whatever the case, McClellan's October 31 memo [the date is a very solid educated guess, it is actually undated, but no other date makes sense] is devoted almost entirely to the movements of the Army of the Potomac. To McClellan, it seems to be no conflict of interest. In his mind, there is only one theater that mattered, Virginia, and the success of the Army of the Potomac is the success of the entire war. He wrote in the memo:

The stake [of the Virginia theater] is so vast, the issue so momentous, & the effect of the next battle will be so important throughout the future as well as the present, that I continue to urge, as I have ever done since I entered upon the command of this army, upon the Govt to devote its energies & its available resources towards increasing the numbers & efficiency of the Army on which its salvation depends.To that end, McClellan revived his plan recommended in early August that the War Department hold all other armies in defensive positions and transfer every unneeded soldier to the Army of the Potomac for offensive operations in Virginia towards Richmond. Here was his largest difference from Winfield Scott, who believed most in a blockade and river war, moving down the Mississippi to fully surround the Confederacy and choke off its economy until cooler heads prevailed in the Southern states (derisively dubbed "the Anaconda Plan").

McClellan believed he would need 208,000 men and 488 guns (meaning artillery pieces) to carry out his plan to seize Richmond, while he estimated that he had about only 168,318 men total spread from Harper's Ferry to Baltimore to Alexandria and 228 guns over the same distance. He estimated the rest of the Union army had 161,000 between Western Virginia, Kentucky, Missouri, and Fort Monroe, from which he expected some 50,000 to be transferred to the Army of the Potomac immediately. He reported his opponent's army at 150,000 and based at Manassas, both of which were wrong (closer to 60,000, including sick, and based on Centreville), but the Scott had been the only person to openly contest McClellan's numbers. Now they would be the accepted reality.

In addition to putting together a strategy document to mark his plan for the war now that he was general-in-chief, McClellan explained another reason for the memo to his wife in his October 31 letter to her:

I have been very busy today writing & am pretty thoroughly tired out. The paper is a very important one--as it is intended to place on record the fact that I have left nothing undone to make this army what it ought to be & that the necessity for delay has not been my fault. I have a set of scamps to deal with--unscrupulous & false--if possible they will throw whatever blame there is on my shoulders, & I do not intend to be sacrificed by such people.The run-on paragraph continues, suggesting McClellan was fiery and worked up when he wrote it.

It is perfectly sickening to have to work with such people & to see the fate of the nation in such hands. I still trust that the all wise Creator does not intend our destruction, & that in his own good time will free the nation from the imbeciles who curse it & will restore us to his favor. I know that as a nation we have grievously sinned, but I trust that there is a limit to his wrath & that ere long we will begin to experience his mercy. But it is terrible to stand by & see the cowardice of the Presdt, the vileness of Seward, & the rascality of Cameron--Welles is an old woman--Bates an old fool. The only man of courage and sense in the Cabinet is Blair, & I do not altogether fancy him!McClellan had apparently been so aggravated by the Cabinet who he had used to help himself usurp Winfield Scott, that he had gone to the nearby house of Edwin Stanton, the former Attorney General now practicing law in Washington City and occasionally giving legal advice to Secretary of War Cameron. "I have not been home for some 3 hrs," McClellan complained to Mary Ellen, "but am "concealed" at Stanton's to dodge all enemies in shape of "browsing" Presdt, etc..." By comparison, the curt message he sent the president himself to excuse not seeing him that day seems congenial: "Please accept my apology for not calling in person as I am very hard at work upon the paper I referred to yesterday."

Most importantly to McClellan was not being blamed if there was no great battle before the winter. He told Mary Ellen that "...it now begins to look as if we are condemned to a winter of inactivity. If it is so the fault will not be mine--there will be that consolation for my conscience, even if the world at large never knows it..." For once McClellan's writing almost shows prescience, since the winter of inactivity that followed in 1861 is widely cited as an example of his reluctance to fight with the army he built. One reason the world at large would never know his wish to fight is that his strategy memo to Cameron advises against it:

So much time has passed & the winter is approaching so rapidly that but two courses are left to the Government, viz: Either to go into winter quarters, or to assume the offensive with forces greatly inferior in numbers to the army I regarded as desirable and necessary.He continues by saying that Cameron could still transfer him immediately all the troops he asked for and there might be time to salvage a campaign. In what should have been recognized as an emerging pattern of behavior for McClellan, he was once again making the desired outcome for his superiors contingent upon them fulfilling an impractical or impossible demand of his.

The strategy memo that emerged from McClellan's sequestration shows that Stanton did more than offer shelter for the general-in-chief on the lam. He also heavily edited McClellan's work. The final copy bears Stanton's handwriting in many places, showing that the lawyer not only offered advice, but actually wrote portions of the strategy. And the memo shows it in some remarkably un-McClellan turns of phrases:

A vigorous employment of these means [of reinforcement] will in my opinion enable the Army of the Potomac to assume successfully this season the offensive operations which ever since entering upon the command it has been my anxious desire & diligent effort to prepare for and prosecute.As Attorney General, Stanton had leaked information about the Buchanan Administration's treatment of the early days of secession to Winfield Scott and Abraham Lincoln. Though a partisan Democrat, Stanton was staunchly Unionist and had abhorred Buchanan's wishy-washy attitude towards secession and the open treason of some of his cabinet, such as Secretary of War John Floyd (who in October 1861 was commanding a Confederate army in southwest Virginia). Since he had left office, Stanton had been itching for a chance to get involved in the war effort, which his close ties to Buchanan seemed to preclude, and he evidently thought the new general-in-chief was a path to power.

Stanton's influence shows in the final paragraph of the memo to Cameron, which he finished this way:

Permit me to add that on this occasion as heretofore it has been my aim neither to exaggerate nor underrate the power of the enemy nor fail to express clearly the means by which in my judgment that power may be broken; urging the energy of preparation & action which has ever been my choice, but with the fixed purpose by no act of mine to expose this government to hazard by premature movement.It was a heavy re-work of McClellan's original draft, which reads much more like the Little Mac we have come to love at this blog:

But I wish to have again on record the fact that I have neither underestimated the force of the enemy nor failed to perceive the means by which that force may be broken. I urge as the only means of salvation the energetic course which has ever been my choice. No time is to be lost--we have lost too much already--every consideration requires us to prepare at once, but not to move until we are ready.Stanton, no doubt, anticipated a productive relationship. Meanwhile McClellan, the memo finished and putting the last touches on his October 31 letter to Mary Ellen, thought of the implications for himself of the changes about to take place:

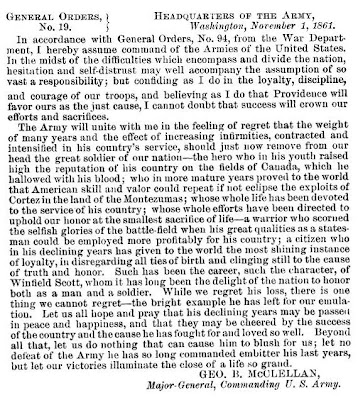

...I saw yesterday Genl Scott's letter asking to be placed on the Retired List... The offer was to be accepted last night & they propose to make me at once Commander in Chief of the Army. I cannot get up any especial feeling about it--I feel the vast responsibility imposes upon [me]. I feel a sense of relief at the prospect of having my own way untrammelled, but I cannot discover in my own heart one symptom of gratified vanity or ambition.McClellan's first act as general-in-chief was issuing General Orders No. 19 thanking Scott for his service. His second was telegraphic Maj. General John C. Fremont commanding the roughly 80,000 Union forces in Missouri and asking him for a complete accounting of his number of soldiers and guns.

Print Sources:

- Sears, 112-123.

No comments:

Post a Comment