Wherein Centreville is captured without very much blood

.........................................................................................................................................

|

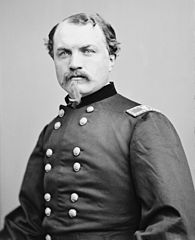

| William W. Averell |

Since March 9, the day after Lincoln's order assigning corps commanders to the Army of the Potomac, Maj. General George B. McClellan's army had been on the move, slowly at first, but gaining speed. Averell's Pennsylvanians had been at the front of that movement.

Company F, which had been part of the tangle with the North Carolina cavalry on the road to Hunter's Mill back in November, had a new captain on March 9, George Johnson, formerly second lieutenant of Company L. Averell had spent the winter as a holy terror to his officers, most of whom he found deficient, to either provoke them to improve their abilities or to drive them from the service. Johnson's predecessor had not passed the test, but the young second lieutenant had been impressive enough to win a double promotion.

The day of his promotion, Captain Johnson was put through the nerve-wracking ordeal of an inspection. Whether Johnson was beside himself or cool and collected, he was responsible not only for making sure all his men turned up in perfect uniform, but then performed the drills asked of them. The inspector was Brig. General Fitz John Porter, leader of one of McClellan's infantry divisions and a known protege of the general-in-chief. Fortunately, it went well:

The review and inspection ended, the officers were summoned in front of the Colonel's quarters. General Porter addressed the officers briefly, congratulated them upon the fine appearance of the troops, and gave utterance to his feelings in remarks of a most flattering character.

Johnson returned to his company to pass on Porter's compliments, but Porter and Averell stayed and discussed plans for the next day. McClellan has chosen Averell, who by March 1862 was commanding a brigade that included his own men and Colonel David McM. Gregg's 8th Pennsylvania Cavalry, to find out if the Confederates were really retreating from the Centreville line they had worked so hard to fortify. The lead units of his forces in the Shenandoah Valley were expected to reach Winchester that day or the next, and McClellan believed that the fall of Winchester would be the trigger for a general Confederate withdrawal.

Sometime around 1:00 am on what was technically March 10, the entire brigade had been roused by the trumpeters blowing the tune "Boots and Saddles" that meant the men were to pack up and go in a hurry. The night was chilly and overcast, with intermittent showers, described as "disagreeable weather." While sergeants turned out anyone not up and about, and supervised preparing marching foods and packing up personal effects, Captain Johnson joined the officers of the 3rd and the 8th in Colonel Averell's tent.

|

| Undated photo of Fairfax Court-House |

The rest of the regiment, though, was in great spirits. They weren't aware that the whole army was at last moving yet, but any cavalryman knew that a brigade of cavalry was more than just a scout--it was the eyes and ears of an army. The brigade rode to Fairfax Court-House [City of Fairfax] via the still very muddy road from Falls Church [US 29], and met there a regiment of New York infantry. They were surprised to learn that the New Yorkers had, in fact, been preceded by a New Jersey infantry regiment. So much for the cavalry leading the army.

It turned out that Brig. General Philip Kearny, commander of the New Jersey Brigade of four infantry regiments from the Garden State, had decided the Confederates were gone. Kearny, the scion of a wealthy New York family that had founded the New York Stock Exchange, cared about nothing so much as being a soldier. Against his parents wishes he had attended West Point, but quit the U.S. Army when war proved scarce, had his famous uncle pull strings to get him detailed as an "observer" to the French cavalry in Napoleon III's invasion of Algeria. He usually observed from the front of the charging horsemen, earning the sobriquet "Kearny the Magnificent" from the Europeans, and publishing a well-read book on cavalry tactics in the United States.

|

| Phil Kearny |

But the U.S. Army generally disagreed, and gave him a recruiting duty tour, followed by an unsatisfying stint murdering natives of Oregon. So Kearny quit, and took a round-the-world trip, trying to make the most of his fabulous wealth as his parents would have preferred. His marriage had been unraveling for years, but his wife refused a divorce, and when he took up with another (younger) woman, the scandal drove them first to New Jersey and then to Paris, where the wed after the divorce was finally granted.

And it was there that Kearny returned to his true love, soldiering. The U.S. Army had little use for him, but Napoleon III was more than happy to commission Kearny an officer in the unit he had fought with in Algeria. At the Battle of Solferino between the allied French and Piedmontese and the opposing Austrians, Kearny led a charge by Napoleon III's personal bodyguard that broke the Austrians and helped win the battle--a battle so miserably bloody that it inspired the first Geneva Convention and the formation of the International Committee of the Red Cross. For his part, Kearny became the first American to ever win the Legion of Honor.

In many ways, Kearny and Averell were opposites. Much older than Averell, Kearny believed morale and vigor won wars, not precision and discipline. He spent lavishly from his personal fortune to equip and supply his men, and was famous for the banquets he hosted for his subordinate officers to boost everyone's spirits. He believed in living large and fighting hard. Already irritated at the difficulty he had had convincing his native country to let him back into service, McClellan's winter of preparation had done nothing but convince him that the U.S. professional military was more interested in parades than in fighting. So when Phil Kearny determined that the Confederates were withdrawing, Phil Kearny decided it was time for his brigade to move, McClellan be damned.

Kearny had already left for Centreville when Averell reached Fairfax Court-House. Rather than chase after them, Averell followed his orders and waited for Fitz John Porter to arrive to discuss the next movement, a careful, and well-considered approach. Then they carried on for Centreville, reaching the edge of the Confederate works about 2:00 pm. The log of the 3rd Pennsylvania records:

The town completely deserted. Found extensive fortifications; batteries and rifle pits, but no ordnance. Quarters sufficient to accommodate a large army, constructed of logs and well plastered, were left standing, and afforded evidence of having been recently occupied. No stores of any kind were left behind.

|

| Centreville in May 1862 |

The abandonment of this line of the Potomac by the enemy ought to be regarded as one of the greatest victories of the war, though a bloodless one. By retiring they have ruined their cause in Europe. They have demoralized their army at home and lost millions of dollars in materials. All this has been achieved for us by McClellan without a battle. The enemy could have made but one blunder greater than this. That would have been to attack us.The reference to millions of dollars in materials was found at Manassas Junction, which Averell reached at about 4:00 pm. The entire place was trashed only hours earlier, in the judgment of whoever had kept the 3rd's log that day. "Before our arrival, Depot car, houses, cars, commissary stores, hotel, etc., were destroyed, and fast becoming a heap of smouldering ashes."

While Averell surveyed the damage at Manassas, McClellan and his large staff were entering Centreville themselves. He had had a scare the day before when news that the Confederate ironclad Virginia had destroyed two of the U.S. Navy's most powerful warships in Hampton Roads, seemingly ending Northern maritime control and indefinitely postponing his plans to move the Army of the Potomac by water to make a stab at Richmond. But before leaving Washington, reassuring news that the new Union ironclad, U.S.S. Monitor, had successfully driven the Virginia back under the safety of Confederate batteries.

In Centreville, McClellan found Phil Kearny waiting for him. The one-armed firebrand theatrically welcomed his general-in-chief, declaring that his men had been the first to arrive, a belief he would cling to dearly for the remainder of his life, no matter how nasty and public Averell's objections were. McClellan was displeased, first, that Kearny had marched without any authority, and second, that his men had been involved in a small skirmish in which several men had been killed. McClellan believed the deaths would have been avoided if Kearny had stuck to the same carefully drawn-up plan as everyone else, but Kearny believed that if he hadn't pushed his men forward, McClellan would have taken several more days to advance. Being first to Centreville was part of this belief.

Then Maj. General Irvin McDowell arrived with his division of infantry and the air of a man retracing the steps of a nightmare. Averell returned to Centreville with his men at 11:30 pm, after a full day in the saddle and went to report to McClellan and learn for the first time about Kearny's claim as well as present his own evidence that he had preceded him by several hours. With Averell's report, it was clear the Confederates were on their way back to their next natural line of defenses, probably the Rappahannock River. That meant McDowell would be advanced to Manassas the next day, site of his greatest failure.

At last McClellan left his troublesome subordinates to spend the night at his new headquarters in Fairfax Court House, which were conveniently Beauregard's old headquarters too. The men of the 3rd Pennsylvania Cavalry "took possession of secession quarters, and prepared to rest both troops and horses from the fatigues of the day." They were surely satisfied to lay their heads down to sleep that first night where no pro-Union soldier had slept since that fateful day in July 1861.

Print Sources:

- Beatie, 71-83

No comments:

Post a Comment