Wherein operations along the Potomac begin McClellan's downfall

...............................................................................................................................

At the beginning of this week we looked at the first of two weeks that changed the American Civil War. The fall of Ft. Donelson on the Cumberland River to the obscure Brig. General Ulysses S. Grant had become a challenge to the general-in-chief of the Northern armies, Maj. General George B. McClellan. As Brig. General George Meade, commanding a brigade in McCall's Division (the Pennsylvania Reserves) put it on February 23 in a letter to his wife: "I fear the victories in the Southwest are going to be injurious to McClellan, by enabling his enemies to say, 'Why cannot you do in Virginia what has been done in Tennessee?'"

In the week that followed he had no choice but to begin an offensive motion with his Army of the Potomac, despite his long-laid plans to move it to the Rappahannock River and march on Richmond. The results of that decision changed the war.

February 24, Monday

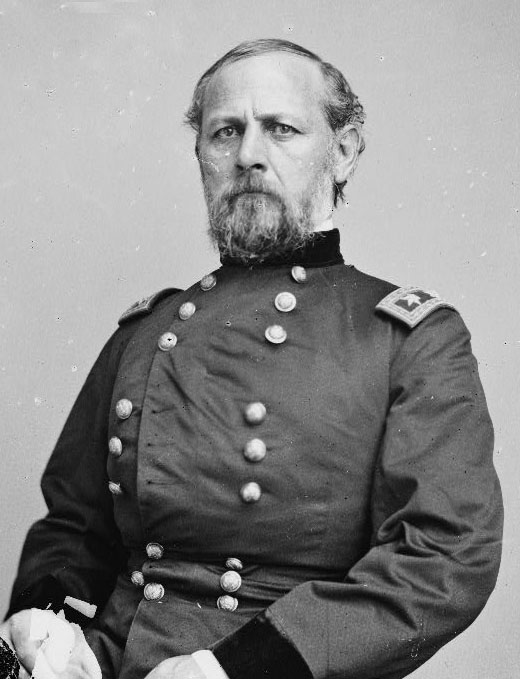

|

| Don Carlos Buell |

He may have gotten Columbia's name wrong, but McClellan's orders set in motion the movement of armies that led to Shiloh, what would be the bloodiest single day in American history until McClellan himself surpassed it at Antietam, and the bloodiest multi-day battle in American history until Gettysburg. The ferociousness of the battle would play a significant role in undermining McClellan's plans for what would become the Peninsula Campaign.

But while Buell's men were reaching the Cumberland, McClellan's had begin crossing the Potomac. Colonel John W. Geary's 28th Pennsylvania from the division of Maj. General Nathaniel P. Banks had arrived at Sandy Hook across from Harper's Ferry in the midst of a driving rainstorm on the night of February 23. The 28th Pennsylvania was an over-sized regiment, and fourteen of its fifteen companies were gathered within a short march of the fork of the Potomac and Shenandoah, along with four guns. Despite the bad weather, Geary stuck to his orders and began crossing men to the Virginia side of the river.

Arriving at Harper's Ferry, we rigged a rope ferry in the course of a few hours, losing 6 men by the upsetting of the skiffs early sent across. The weather, at first slightly perverse, became so exceedingly violent, and the river rose so rapidly that it became dangerous to attempt to throw troops across.

|

| The New York Avenue Presbyterian Church in 1920 |

His men of power sat around him - McClellan, with a moist eye when he bowed in prayer, as I could see from where I stood; and Chase and Seward, with their austere features at work; and senators, and ambassadors, and soldiers, all struggling with their tears - great harts sorrowing with the President as a stricken man and a brother.Gurley would eulogize Lincoln himself just three years later. When the service was concluded the mourners followed the procession to Oak Hill Cemetery Chapel above Georgetown, a chapel designed by the architect of the Smithsonian's Castle Building, James Renwick, in a cemetery founded by William Wilson Corcoran, namesake and founder of the art gallery as well as Riggs Bank [now owned by PNC], though in 1862 he was in exile in Paris as a Southern sympathizer. Willie was laid to rest in a family vault belonging to a branch of the Carroll family headed by New York Supreme Court Clerk William T. Carroll.

Carroll was also the father-in-law of Captain Charles Griffin, who had married his daughter Sallie after recovering from his nearly deadly wounds received at Bull Run when he pushed his West Point Battery up to nearly point-blank range on Henry Hill and opened fire on the men of "Stonewall" Jackson. Confusion about the blue uniforms of Jackson's 33rd Virginia had led to his capture and the death of most of his men. Carroll's oldest son, Colonel Samuel Spriggs Carroll, was leading the 8th Ohio at Paw Paw Tunnel on the Potomac above Harper's Ferry, with the rest of Lander's Division closing in on Jackson at Winchester.

On this momentous Monday, Jackson was well aware of the threat from Lander's Division, a two days' march through mountain passes from Winchester. Jackson had already blunted an attack by it along a similar route in the winter. But what did General Joseph E. Johnston, commander of all the Confederate forces north of the Rappahannock River want him to do if Lander attacked? Jackson knew that Johnston was considering moving south of the Rappahannock, where he could defend with fewer troops. So fall back with the rest of the army or stand and fight?

The subject of fortifying is of such importance as to induce me to consult you before moving in the matter. If you think that this place will be adequately re-enforced if attacked, then it appears to me that it should be strongly fortified. I have reason to believe that the enemy design advancing on this place in large force.What Jackson was not counting on was a direct move across the Potomac at Harper's Ferry, and that's what Colonel Geary's Pennsylvania men had spent the afternoon and evening doing, until the storm had become so fierce that the regiment was split on either side of the river. "The storm raged all night of the 24th," he wrote.

Rebel cavalry scouts had been seen in the evening upon the hills beyond Bolivar [Heights], and as it was impossible to re-enforce the pioneers [building a temporary bridge], consisting of 2 commissioned officers and 6 privates, we guarded their position by artillery and infantry on the Maryland side.February 25, Tuesday

By morning the storm had eased and Geary had to deal with the challenge of crossing his men over the swollen river.

In the morning a calm ensued, and eight companies and a section of artillery were at once thrown over, and pickets were posted for a circuit of several miles, extending beyond Bolivar. The rope breaking and river running rapidly compelled me to transport two more companies in boats.Geary's men were over, but were in the same precarious position the troops at Ball's Bluff had been in--a wide, deep river, with very few means of transport for reinforcements or retreat. A bridge would need to be established of some kind to march the rest of Banks' Division over the Potomac as well as the three other divisions McClellan planned to cross. The division that had suffered the catastrophe at Ball's Bluff, now lead by Brig. General John Sedgwick, began marching through the mud from its positions around Poolesville towards Sandy Hook.

Also slated for movement to the Valley was the Pennsylvania Reserves, who were ordered to strike their camp at Langley and cook three days' rations. Before the order came down, George Meade had found some time to write to his wife, again commenting on McClellan's position.

I am sorry to hear people talk [bad about McClellan] who ought to know better, and from all I can learn McClellan's star is rapidly setting, and nothing but a victory can save him from ruin. It is well known that his victories in Western Virginia last summer precipitated and caused Bull Run. Now the victories in Tennessee are forcing a movement here, with, I trust and believe, a better result than was obtained last summer.The man who had sneaked away from Winchester to Manassas in order to cause that bad result, Joe Johnston, was now frustratedly trying to avoid the Northern army. "The accumulation of subsistence stores at Manassas is now a great evil," he wrote to Jefferson Davis on Tuesday, reversing six months of constant complaining about the lack of stores at Manassas Junction because now he was trying to leave the area, not stay.

The Commissary General was requested more than once to suspend those supplies. A very extensive meat packing establishment at Thoroughfare is also a great incumbrance [sic]. The great quantities of personal property in our camps is a still greater one. Much of both kinds of property must be sacrificed in the contemplated movement.But while materiel was finally in abundance, personnel had reached a critical low.

The army is crippled and its discipline greatly impaired by the want of general officers. The four regiments observing the fords of the Lower Occoquan are commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and besides a division of five brigades is without generals and at least half the field officers are absent--generally sick.The Confederacy's Army of the Potomac was in no shape to fight a Northern advance. The lack of command on the Lower Occoquan was of particular concern to Johnston, because he expected the division of Brig. General Joe Hooker in Charles County, Maryland, to cross the Lower Potomac at any day, sweep the batteries along the Potomac, unite with Sam Heintzelman's division marching from present-day Fort Belvoir, and get between his army and Richmond.

Johnston was correct, that was precisely what McClellan planned, and that afternoon he dispatched his chief engineer, Brig. General John Barnard, to Charles County to help Hooker prepare for the attack. That evening a telegraph informed the capital that Nashville had fallen to Don Carlos Buell.

February 26, Wednesday

"If this move fails," McClellan boldly told Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton on Wednesday morning, "I will have no one to blame but myself. He was giving the President and Secretary one last briefing of his plans for the twin movements on Winchester and Occoquan before leaving to command the larger one personally. The general-in-chief, after months of planning and drilling, was going to take the field.

At 1:00 pm, McClellan and his massive retinue of aides reached Sandy Hook and detrained. Nathaniel Banks met him there, and the two rode to opposite Harper's Ferry together. Colonel Geary's Pennsylvanians had been reinforced during the night by some of McClellan's engineers and a work party of the 3rd Wisconsin, who were constructing a pontoon bridge for crossing Banks' Division. According to McClellan's aide, Captain Louis Philippe d'Orleans--the grandson of a deposed king of France, known more properly as the Comte de Paris, and brother of Robert d'Orleans--when the bridge was finished, McClellan himself was the first to cross it. Finding it satisfactory, he ordered two brigades of Banks' three over it, and joined Banks for a part tour and part inspection of Harper's Ferry.

After fortifying the heights above Harper's Ferry, McClellan turned next to the pontoon bridge. It was a small, narrow, rickety thing, and the rain was picking up again, making it even more precarious. McClellan's plan called for rebuilding the B&O Railroad bridge dynamited on orders from Joe Johnston and carried out by Jackson in the summer when they retreated to Winchester. In the meantime, he would have his engineers build a larger, sturdier pontoon bridge out of canal boats confiscated from the C&O Canal and in the process of being moved to Sandy Hook.

After sighting the future bigger pontoon bridge, McClellan supervised the crossing of Banks' final brigade, as well as the first brigade from Sedgwick's Division, and sent orders that another division, that of Brig. General Erasmus D. Keyes, begin its march so that it could cross on the 28th, over the newer bridge. McClellan and his staff left Banks in Harper's Ferry and crossed the rickety bridge--Captain Orleans observed in his diary that "one can't help trembling upon thinking about all the ways it could be carried away"--and returned to Sandy Hook.

At 10:20 pm, McClellan sent a self-congratulatory telegraph to Stanton, full of citations for junior officers as if the job was done.

The bridge was splendidly thrown by Captain Duane, assisted by Lieutenants Babcock, Reese, and Cross. It was one of the most difficult operations of the kind ever performed... Colonel Geary deserves praise for the manner in which he occupied Virginia and crossed after the construction of the bridge. We will attempt the canal boat bridge tomorrow. The spirit of the troops is most excellent. They are in the mood to fight anything. It is raining hard but most of the troops are in houses.February 27, Thursday

"We are all agog in readiness to move at short notice," George Meade wrote to his wife from the Pennsylvania Reserves' camp in Langley. "Rumor has it that Banks above and Hooker below have both either crossed or are crossing."

McClellan also wrote his wife that morning: "You have no idea how the wind is blowing now--a perfect tornado--it makes the crossing of the river very difficult & interferes with everything. I am anxious about our bridge."

The rain had, at least, stopped. McClellan had gotten only a few hours of sleep, his last order one to Colonel George Gordon at 3:00 am to take two regiments of infantry, eight companies of cavalry, and four guns to Charlestown at dawn in order to either occupy the town or find Jackson.

Jackson's cavalry pickets galloped back to Winchester from Charlestown later that day to let him know that Federal troops were now in force to his northwest and north. The news confirmed the suspicions of Jackson, who had sent word to Johnston the night before that Banks had taken Harper's Ferry and was probably headed to Winchester next. Johnston sent the word to his right flank on Thursday, headed by Brig. General William H.C. Whiting, who was worried himself about Hooker's impending attack.

In case of advance, look that we are not separated. If the enemy's army is divided, the distance between ought not to be so great as from this turnpike [US29] to the Telegraph road. The two portions would have one first object: to defeat our army... The enemy is in force at Harper's Ferry, and also at Hancock and Frederick. Many wagons have been sent from Baltimore to Hagerstown. They will soon move upon Winchester, so threatening our left flank.But things were going better for Whiting than he realized. Across the Potomac, McClellan's Chief Engineer, John Barnard, was not pleased with the plan Hooker had been working on for weeks. Barnard, a humorless scold of an officer who was nonetheless frequently correct, had decided upon viewing the ground himself that Hooker was off his rocker to suggest such a plan with only his division.

"It would require a lengthy letter or verbal communication to communicate my views," he telegraphed to McClellan from Hooker's headquarters at Budd's Ferry.

In the first place, I state explicitly that I consider any operation which involves re-embarking... to be most unwise, and to involve not merely risk, but probable disaster. Second. I believe that the floating force may be landed... higher up, conjointly with... Heintzelman... Third. The operation [done correctly] involves the cooperation of three divisions and the navy and should be directed by yourself in person, or by a general officer in command of the entire force.Barnard concluded that without committing a large force "it is better to let the batteries alone than to undertake to silence them by landing and disembarkation."

The telegram hadn't yet reached McClellan when disaster struck. The canal boats that had been brought up the C&O Canal couldn't make it through the final locks at Harper's Ferry--they were several inches too wide! The locks had been constructed to match the smaller Shenandoah canal boats and there was now no way to get the slightly larger C&O Canal boats out into the river to build the sturdier pontoon bridge.

At 1:00 pm, after wrestling with several ideas to move the boats, McClellan telegraphed his chief of staff, Brig. General Randolph Marcy, still in Washington: "Do not send the regular infantry until further orders. Give Hooker orders not to move until further orders." By 3:30, McClellan admitted partial failure and telegraphed the Secretary of War.

The lift lock is too small to permit the canal boats to enter the river, so that it is impossible to construct the permanent bridge as I intended. I shall probably be obliged to fall back upon the safe and slow plan of merely covering the reconstruction of the railroad. This will be done at once, but will be tedious. I cannot, as things now are, be sure of my supplies for the force necessary to seize Winchester, which is probably re-enforced from Manassas. The wiser plan is to rebuild the railroad bridge as rapidly as possible, and then act according to the state of affairs.Stanton was livid. "If the lift lock is not big enough, why cannot it be made big enough," he demanded. "Please answer immediately."

McClellan didn't, probably because of a combination of irritation at the question and wanting to seek out the feasibility of the option. Instead, McClellan set to work making sure that the other parts of his army stood down from their movements, so that Sandy Hook would not become overwhelmed by massive numbers of troops.

Sometime in the evening, either Barnard's telegram or an emphatic follow-up to the same effect, reached McClellan. "Revoke Hooker's authority in accordance with Barnard's opinion," he told Marcy at 8:00 pm. But McClellan saw an opportunity to perhaps salvage something. "Immediately on my return we will take the other plan and push on vigorously."

Finally, at 10:30 pm, he warily responded to Stanton:

It can be enlarged, but entire masonry must be destroyed and rebuilt, and new gates made; an operation impossible in the present stage of water, and requiring many weeks at any time. The railroad bridge can be rebuilt many weeks before this could be done.It was much too late. Marcy had already been to the White House where Lincoln and Stanton both had cursed him and McClellan out.

February 28, Friday

The upshot from the canal boat debacle continued. "What do you propose to do with the troops that have crossed the Potomac?" Stanton tersely telegraphed McClellan at 1:00 pm. The general-in-chief had actually already been working on that. That morning he had rode out with a strong column of Banks' men to Charlestown and made a show of inspecting the town, including sending a telegram to Stanton half an hour before the Secretary of War's telegram, which he probably did not see first.

I have decided to occupy this town [Charlestown] permanently, and am arranging accordingly. I make other arrangements on the right which render us secure. You will be satisfied when I see you that I have acted wisely, and have everything in hand.At 2:00, he ordered Lander's Division to Martinsburg as quickly as possible. Once there, he was to touch base with Banks, and the two of them should decide whether or not to advance on Winchester, with the understanding that no reliable reinforcements would be available until the railroad bridge was completed. Satisfied that he had made the best of the situation, he set off for Sandy Hook and the train ride back to Washington to face the President.

Unaware that McClellan had been humiliated, Johnston in Centreville was growing increasingly impatient with Richmond's lack of support for his army. On Friday, he wrote to Whiting at Dumfries about the impending withdrawal of the army from Northern Virginia.

Publish nothing about the move until we are all ready. We may indeed have to start before we are ready. General Hill reports that the enemy has crossed the Potomac at Harper's Ferry on a pontoon bridge, and yesterday occupied Charlestown. His scout reported the size of of the train of the latter troops seventy-two wagons. He is also occupying the Loudoun Heights. If he drives Jackson out of Winchester we shall be compelled to fall back at once. I have some apprehension that he may attempt the turning operation through Loudoun by crossing the Shenandoah and taking the road at the end of the mountain.At the same time in Richmond, Jefferson Davis was writing Johnston one of his famous loquacious letters. After many words with contradictory or unhelpful advice, Davis concluded dramatically:

Recent disasters have depressed the weak and are depriving us of the aid of the wavering; traitors show the tendencies heretofore concealed, and the selfish grow clamorous for local and personal interests. At such an hour, the wisdom of the trained and the steadiness of the brave possess a double value. The military paradox that impossibilities must be rendered possible had never better occasion for its application.Johnston could expect no help from Richmond.

"I received last evening the instructions of the Major General Commanding to suspend my movement across the river until further orders," Hooker passive aggressively complained to headquarters. "Of course it is not for me to know or inquire for influences at work to bring about this suspension."

Nevertheless he proceeded to protest that until Barnard's visit, every officer from Washington who visited Budd's Ferry was enthusiastic about the plan. Perhaps betraying the personal ambition that lay behind its hatching, he mused that because of this support "it ought no longer to be considered as an adventure of strictly a private character." He concluded by showing he was still preparing for the attack, in case McClellan gave him the green light again:

I have found but one opportunity to experiment with the Whitworth. From that, I am satisfied that they are unrivaled pieces for accuracy of shooting and length of rang.e Should have gone out with them again to day but for the high wind; it blows a gale.McClellan arrived in the afternoon and was immediately ushered into the White House, where an explanation was demanded not only by Lincoln and Stanton, but Senators Ben Wade and Andrew Johnson of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. He was dismissed by the President with a warning that he had ten days to submit a plan for a campaign by the Army of the Potomac or he would be sacked, but Wade and Johnson stayed on to bash McClellan to Lincoln and insist he needed to be removed. For his part, Stanton dragged McClellan back to his office at the War Department for another round, during which the general-in-chief promised a memorandum by the next day explaining everything.

March 1, Saturday

Joe Johnston, knowing his movement south to the Rappahannock was imminent, nevertheless took time to sit down and write out a lengthy list of grievances to Jefferson Davis about his friend and Secretary of War, Judah P. Benjamin. Benjamin's direct granting of furloughs, permission for conversion of infantry companies into artillery, and general meddling in the command structure of Johnston's Army of the Potomac had irked Johnston for months. He indulged in his occasional vice of sanctimony, concluding:

My object in writing to your excellency on this subject is to invoke your protection of the discipline and organization of this army. My position makes me responsible for the former, but the corresponding authority has been taken from me. Let me urge its restoration. The course of the Secretary of War has not only impaired discipline, but deprived me of the influence in the army, without which there can be little hope of success. I have respectfully remonstrated with the honorable Secretary, but without securing his notice.But while Johnston attacked Davis' personal friend, Lander's Division was on the move to Martinsburg, where it would be able to prepare to join up with Banks' Division and outnumber Jackson at Winchester nearly 5-to-1. Lander himself was slipping in and out of a fevered unconsciousness. He was facing a severe infection from his foot wounded at Edwards' Ferry the day after Ball's Bluff, and the fiery general had refused to leave his division to recover.

For the rest of the Army of the Potomac not in Lander's or Banks' Division, the Saturday passed tediously. George Meade was growing frustrated with the lack of news, but took the time to let his wife know that at least it hadn't been as bad as Friday.

Yesterday was a very disagreeable day, extremely cold, with a very high wind, and blustering weather. I was obliged to be exposed, standing in the wind from 9 in the morning till 5 in the afternoon, mustering the several regiments of my brigade... We are all in the dark as to where or what direction we move.McClellan, meanwhile, put the finishing touches on two memos--one to explain Harper's Ferry and another to explain the Occoquan, for good measure. He delivered them to Stanton, but what Stanton did with them is unknown. The Secretary swore later that he gave them to the President, while McClellan swore based on later conversations with Lincoln that he never did.

March 2, Sunday

On a quiet day along the Potomac after two weeks of chaos, Frederick Lander died. A heavy snowstorm led his adjutant to move the division back out of the mountains to Paw Paw, postponing its arrival in Martinsburg. McClellan ordered them to resume the march and named Brig. General James Shields to replace Lander.

In Washington, for the first time ever, McClellan called a council of war of all his division commanders.

Epilogue

The two weeks at the end of February that mark McClellan's aborted campaign set into motion war-wide changes. The most immediately apparent was the change in McClellan's stature itself. His failure to execute the double flanking maneuver, and the dimwitted reason for its collapse, convinced Lincoln and especially Stanton that Little Mac would not be able to provide victory. In short order, it would lead to Lincoln's meddling in the structure of the army to create rival power centers to McClellan, McClellan's dismissal as general-in-chief, and Lincoln's active search for a replacement to McClellan. All of these moves would undercut the the next year of the war effort, before it had a chance to sink or swim on its own.

And after his lambasting on February 28, McClellan also lost his confidence in the ability to persuade Lincoln and Stanton. His obnoxious self-assurance would curdle into a surly self-righteousness after especially Stanton's harsh criticisms. The subsequent poor communication and dissembling that so infuriated the Secretary throughout the Peninsula Campaign has its seeds in the failures of February 27.

McClellan's inability to follow up Ft. Donelson with a similar victory in the East would also damage public perception of the Army of the Potomac. The army with the most reporters following it and the best infrastructure for sharing its story with the most people, the perception that the North was lead by incompetent generals that were more interested in politics than winning wars survives to this day in the common misconception that the North lost every battle until Gettysburg.

But these two weeks changed the South too. Joe Johnston was already beginning his evacuation to south of the Rappahannock on March 2, yielding some of Virginia's best farmland to the Northern armies as well as the battlefield he and Beauregard had held in 1861. From now on Johnston would be further than a day's march from Washington, reducing the pressure that was bankrupting the Lincoln administration (who had created national paper currency for the first time in U.S. history to fund the war). Johnston's retreat and his ongoing war against the War Department would permanently damage his standing with Jefferson Davis, in much the same way McClellan's was damaged with Lincoln.

Johnston was retreating, because despite McClellan's bungling of the operation, the seizure of Charlestown had set in motion events that would make Johnston's fortress at Centreville untenable. As soon as Strasburg--within striking distance of Winchester--fell, Johnston would have to abandon it, since the rail ran directly from there to Manassas--behind his army. To give Johnston time to retreat, a bold, and slightly crazy, campaign would be needed in the Valley, and the Confederacy had the right man in Stonewall Jackson. Lander's replacement by Shields would ensure that the North had exactly the wrong man opposing him.

And finally, the loss of Nashville and the looming loss of Manassas caused Jefferson Davis to recall to Richmond to advise him the one Confederate general whose opinions he actually listened to from his work fortifying South Carolina--Robert E. Lee.

No comments:

Post a Comment