.....................................................................................................................................................

Shortly after 10:00 am, McDowell recognized that he could

filibuster no longer, and would have to implement Pope’s orders or risk

derailing the entire plan of battle. Porter may have pointed this out to him,

or (less likely given his personality) waited until McDowell arrived at it

himself. The generals broke up their meeting and sent their various staff off

to set the column in motion.

Porter had agreed to let McDowell issue orders to King’s

division (still being commanded by Hatch) to march, and also to let stand aside

to let the Fifth Corps pass it so it would not be separated so far from the

rest of McDowell’s corps. Porter was only too happy to have his men in the

front of the column. As McDowell rode to tell them, he was alerted that

Ricketts’ division had completed their march from Bristoe that morning. Now

that he had two of his three divisions in the same place again, things were

beginning to come together for McDowell.

Centreville

Things were going even better for McDowell than he realized.

John Pope had received dispatches from both Porter and McDowell, each

complaining about the other and both complaining about their orders. Irritably,

Pope sat down to untangle the entire matter and issued an identical order to

both of them to explain what they needed to get about doing.

You will please move forward with your joint commands toward Gainesville. I sent General Porter written orders to that effect an hour. and a half ago. Heintzelman, Sigel, and Reno are moving on the Warrenton turnpike, and must now be nut far from Gainesville. I desire that as soon as communication is established between this force and your own. the whole command shall halt. It may be necessary to fall back behind Bull Run at Centreville to-night. I presume it will be so, on account of our supplies. If any considerable advantages are to be gained by departing from this order it will not be strictly carried ont. One thing mew. that the troops must occupy a position from which they can reach Bull Run, to-night or by morning. The indications are that the whole force of the enemy is moving in this direction at a pace that will bring them here by to- morrow night or the next day.

Having set his subordinates straight, Pope packed up his

headquarters and rode past the Ninth Corps men marching towards Stone Bridge to

catch up with Heintzelman and his two divisions.

Groveton

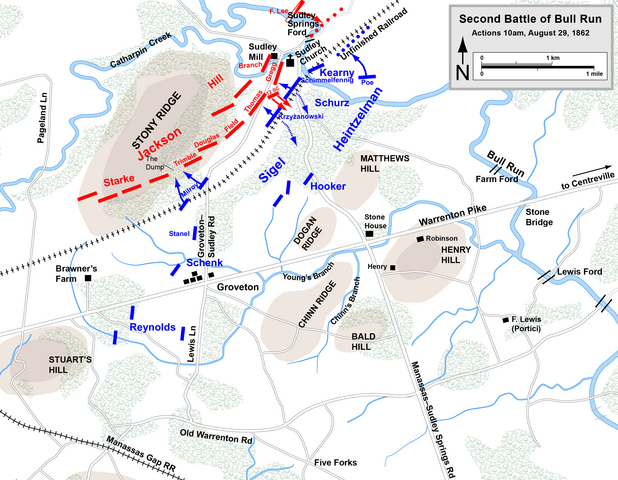

Meanwhile, north of Groveton, Milroy had come up with a plan

for his remaining two regiments. He would attack the flank of the supposed

Confederate rearguard division that was harassing Schenck’s division with

artillery fire, which he presumed must be on the edge of the Brawner property

and anchored on Groveton-Sudley Road [Featherbed Lane]. The 82nd Ohio

and 5th [West] Virginia regiments marched quickly towards the berm of

the Unfinished Railroad that crossed Groveton-Sudley Road [Featherbed Lane].

A soldier from the 82nd wrote that “within a few

paces… [the Confederates sprang from behind the berm] and with a wild yell

poured a deadly volley full into our faces.” The Ohio colonel urged his men

forward, even as the loyal Virginians staggered and hunkered down. Running at

the railroad berm they “commenced

scaling the embankment, a portion of the regiment passing it through an opening

for a culvert. Just at this moment a large force of Rebels appeared on the

regiment’s right flank.”

It was either the 12th Georgia or else a

detachment of the 15th Alabama immediately in front of the Ohio men,

part of Trimble’s brigade of Ewell’s division that Milroy thought were far out

to his left fighting Schneck at Brawner’s Farm. In the fierce crossfire, the

colonel of the 82nd Ohio was killed instantly when a ball struck him

in the head. The men began to fall back rapidly onto the already beleaguered 5th

[West] Virginia, and Milroy was at suddenly risk of being complete overwhelmed

by a force that was much, much larger than he had anticipated.

Brawner’s

While Milroy launched his misguided flank, the general he

was supposedly bailing out was trying to stabilize his own position. Under

steady artillery fire, Robert Schneck was trying to place the two brigades of

his division on a perpendicular line straddling the Turnpike north and south at

the east edge of the Brawner Wood. He expected Milroy’s brigade to extend his

right flank north to the Unfinished Railroad and Reynolds’ division to take up

the line on the south. It wasn’t quite where Pope had wanted the men of Sigel’s

First Corps, Army of Virginia, but it would meet the threat at Brawner’s Farm

of Jackson’s supposed rearguard.

Schenck was startled to learn that the two regiments of

Milroy’s that had already been sent to link up with his right flank had been

recalled. Milroy’s remaining two regiments, they told him, had been surprised

by a very large Confederate force that had been hiding north on Groveton-Sudley

Road [Featherbed Lane]. And not only did Milroy need his entire brigade, but he

needed reinforcements fast. Schenck quickly ordered his brigade north of the

Turnpike to turn 135 degrees to their right and rush to Milroy’s support.

Things were clearly not what they seemed.

On Stuart’s Hill at the intersection of Pageland Lane and

the Turnpike, where less than a day before John Gibbon had come under fire,

James Longstreet rode with his men. Hood’s Division had been the first on the

field, and replaced the two brigades of Jackson that had been skirmishing with

the Pennsylvania Bucktails. With one brigade on either side of the Turnpike,

Hood began moving them forward against the Pennsylvanians immediately, his old

Texas Brigade displacing the Bucktail skirmishers, who nevertheless fell back

doggedly.

Meanwhile, Longstreet and Lee had found Jackson north of the

Brawner farm and discussed the situation with him. Lee couldn’t have been more

pleased. His army would soon be reunited into one whole, meanwhile his opponent

was scattered all over northern Virginia and even in the immediate vicinity was

deploying piecemeal. Longstreet was sent to place his remaining brigades out to

Hood’s right, to turn the Confederate position into a giant set of open jaws.

Opposite Longstreet’s arriving men, in blue, George Meade

quickly figured out that he was rapidly becoming outnumbered. As the Bucktails

fell back and his own brigade of Pennsylvania Reserves began to bear the brunt

of the Texan advance, Meade sent a messenger flying to John Reynolds for the

remainder of the division, and to Robert Schenck for reinforcements from the

First Corps men. Reynolds immediately sent forward another brigade of Pennsylvanians,

who rushed through a ravine to Meadowville Lane, but were surprised to come

under fire not from the direction of the fighting Meade was doing, but from due

west. Yet another brigade of Confederates had appeared!

These were the lead brigade of Neighbor Jones, turning off

from Pageland Lane and immediately going into battle, the rest of their

division not far behind. Schenck, meanwhile, sent his regrets to Reynolds that

he had only one brigade left, having sent the other to rescue Milroy. Reynolds

quickly ordered his own remaining brigade of Pennsylvanians to march behind

Meade’s men and fill in the gap with the other brigade, to avoid the threat of

being split in half by Jones’ division. But it was just meant to buy time, and

he sent orders for the whole division to fall back to Lewis Lane [Groveton Rd]

once everyone was in position. Schenck would do the same.

Sudley Springs

As Longstreet’s men arrived on the southwest side of the

battlefield, Maj. General Phil Kearny led his division into battle to the

northeast. While Maj. General Sam Heintzelman was technically the commander of

the Third Corps, Army of the Potomac, Kearny’s larger-than-life antics and commanding

personality made his arrival the greater morale-boost to the confused First

Corps, Army of the Virginia. With typical dramatic flair, Kearny summoned the

First Corps division commander Carl Schurz to give him a situation report,

after sending his first brigade into battle to sure-up Schurz men.

Schurz’s division was heavily engaged along the Unfinished

Railroad just to the west of Sudley Road against a Confederate force of at

least several brigades that wasn’t supposed to be there. Worse, the two

brigades had a gap between them that the Confederate commander, Maxcy Gregg,

was trying to hammer open further. The 1st New York of Kearny’s lead

brigade was placed directly in this gap. Its major, leading the regiment

because of casualties, wrote:

I immediately put the regiment in motion and advanced to within 50 yards of the railroad, when I was attacked by a very heavy force of the enemy. The regiment returned the fire with great vigor, driving the enemy behind the bank caused by filling a low piece of ground for the road.

The rest of the brigade, however, did not join the New Yorkers

in the gap. Kearny had asked Schurz to shift his whole force to the left so

that he could put his division into battle along the Sudley Road without having

to split it. When Heintzelman learned this, he fumed. He had told Kearny to

immediately go into battle wherever Schurz was weak, just like his other

division under Joe Hooker was now marching as fast as possible to reinforce

Milroy and Schenck.

Instead, Kearny had ordered one brigade to ford Bull Run and

was maneuvering the other two towards Sudley Church for an imagined flank

attack. Heintzelman (and Schurz) were pretty sure that by the time Kearny was

ready for his attack, the Confederates would already have crushed the wavering

men of the First Corps.

The major of the 1st New York recorded the stress

from the point of view of soldiers on the battlefield:

After holding this position [50 yards from the railroad] about half an hour I found that the enemy was swinging around my flanks, and had succeeded on the left in getting so far behind me that I mistook their fire for that of our own troops coming to my relief, but on turning in that direction I saw the error, and ordered the regiment to retire. About 300 yards from the first point of attack I reformed the regiment under fire, and held the enemy at this point for one half-hour. The men seemed determined not to be forced from this ground, but, the enemy getting around both of my flanks, I found it necessary to take a new position farther to the rear, while I anxiously looked for help, but none came.

The rest of his brigade was marching into the position near

Sudley Church. At the same time the sister brigade that had crossed Bull Run

was unknowingly about to flank Jackson’s line and capture all of his supply

wagons. Seeing their skirmish line march up the gradual hill, Brig. General

Fitzhugh Lee sent six companies of the 1st Virginia Cavalry and

Pelham’s horse artillery to bluff them away.

No comments:

Post a Comment