...........................................................................................................................................

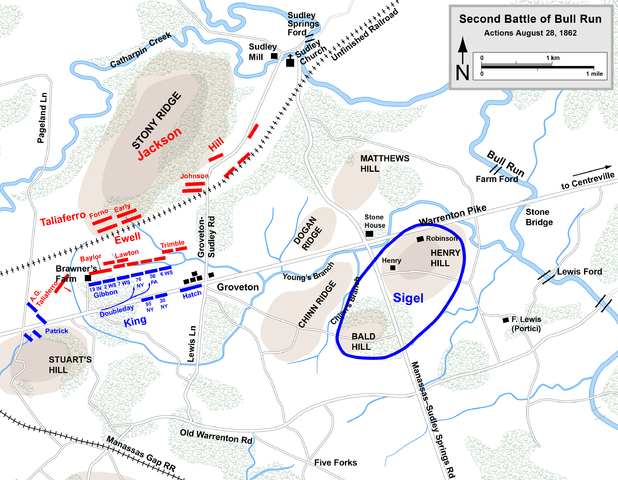

The fight at Brawner’s Farm had metastasized into something

primitive. The green men of Gibbon’s brigade stood in their black Hardee hats

and took the fire from the storied Stonewall Brigade and Lawton’s Georgia

Brigade standing less than half a football field away, returning it shot for

shot. It was more like something out of the American Revolution, when primitive

musketry made aiming a futile exercise.

With the 6th Wisconsin, isolated by several hundred yards on

the far left, Major Rufus Dawes, future brigade commander, described the madness

up and down the line:

Our men on the left loaded and fired with the energy of madmen, and the 6th worked with equal desperation. This stopped the rush of the enemy and they halted and fired upon us their deadly musketry. During a few awful moments, I could see by the lurid light of the powder flashes, the whole of both lines. The two ... were within ... fifty yards of each other pouring musketry into each other as fast as men could load and shoot.

Jackson, determined to turn the tide, directed Ewell to

Isaac Trimble’s brigade against the 6th Wisconsin. The hardscrabble Dick Ewell

chose to accompany them himself. With Trimble’s 12th Georgia, on the

far left of the brigade, Ewell scampered down into a ravine, where it was

suddenly swept by a crossfire. Ewell scouted ahead and dropped under the cover

of a cluster of pine trees to look for the source. Suddenly a bullet struck his

knee, splitting in kneecap. The general writhed in pain, and—either at his

direction or because of the heat of battle—was left behind.

Trimble’s men surged forward, threatening to overwhelm the

6th Wisconsin, but Doubleday’s two regiments of reinforcements arrived in time

to drive them back. Gibbon now had a thin, uninterrupted line of six regiments

stretching from the Brawner Farmhouse to a small creek connected to the ravine

Dick Ewell had been wounded in. George Noyes, a junior officer in Doubleday’s

brigade described the scene:

The shadows of night gradually descended and it seemed to me that I saw at least a mile of lightning leaping from rebel muskets, while a perfect deluge of rebel thunderbolts went crashing into the woods, or came shrieking like fiends over and among us. The rattle of musketry was terrible and continuous—the air seemed full of lead.

On the far end of this deluge was John Gibbon, having placed

himself at the weakest point of the line, his open left flank. Resting on the

Brawner Farmhouse, the 19th Indiana had no recourse if the Confederates moved

in the gap between an intermittent stream and the farmhouse. They had already

placed horse artillery on the other side of the ravine and were raining down

shot on the Hoosiers.

The colonel of the 19th ordered two companies to redeploy at

a right angle and open fire on the nearby horse artillery. In Union accounts,

this forced the guns to relocate. In the account of John Pelham, the battery

commander, the fire was ineffective and his gunners kept firing throughout.

Either way, Gibbon had to deal with a bigger problem, the arrival of a brigade

under the command of Alexander Taliaferro, the uncle of division commander

William Taliaferro.

Gibbon ordered the 19th's colonel to form an oblique angle

with his regiment so it could fight the Stonewall Brigade and Taliaferro’s

advancing brigade. But the colonel decided instead to move his regiment back

several dozen yards behind a rail fence, so that Taliaferro’s angle of attack

in the dark would allow the Hoosiers a shot at his flank instead. It was a

dangerous move to perform with rookie soldiers facing nearly 3:1 odds, but it

worked perfectly, even after Taliaferro ordered his men to charge and prevent

them from executing the maneuver.

In the middle of Gibbon’s line, the Confederates tried to breakthrough

too, with regiments of the Stonewall Brigade and Lawton’s Georgia Brigade

advancing and falling back throughout the hour and a half of heavy fighting.

During one, the commander of Jackson’s Division, William Taliaferro, took a

bullet to the leg and had to be carried off the field, further confusing an

already confusing situation. With Ewell and Taliaferro both gone, Jackson was

giving orders to brigade commanders and sometimes regiments himself, and

showing the limitation of his tactical imagination to enduring frontal

pummeling, followed by all-out charges.

It was time for the latter tactic. About 7:30 Jackson sent

at least two of Lawton’s Georgia regiments and perhaps the 2nd Virginia (who

surely did not feel kindly towards the Georgians) in an all out charge against

the 2nd Wisconsin just to the right of the 19th Indiana, the rebel yell rolling

over the battlefield above the din of muskets and boom of cannon. The Badger

State men stood firm and fired into the incoming mob, then endured the crash of

hand-to-hand combat.

Meanwhile, two regiments to the right, the 76th New York

from Doubleday’s brigade took advantage of the momentary relaxation on their

front caused by the charge. Their colonel bellowed for his men to reform at a

sharp angle from the line, facing the flank of the charging Confederates and

open fire. One member of the regiment wrote:

It seemed like one gun… When the smoke cleared away a little, the few left of that mass of human beings who had so rapidly left the woods a few minutes before had disappeared, but the ground was literally covered with their dead and wounded.

The charge repulsed, the 76th's colonel ordered his men to

fix bayonets and prepare for a countercharge.

Sudley Springs

No comments:

Post a Comment