Wherein McClellan tries to escape Washington

...................................................................................................................................................

On March 31, 1862, the wharfs at Alexandria were a flurry of activity. The largest army that the United States had ever seen had been sailing out of the port for Fort Monroe on the Virginia Peninsula, and the previous two weeks men, animals, and supplies from all over the North had squeezed their way through the narrow streets to board the rickety ships converted from civilian use to transport them.

The man orchestrating it all was Maj. General George B. McClellan, one time general-in-chief of the U.S. Army, now confined only to command the Department of the Potomac. In the months since

he returned from his illness, McClellan had become deeply unhappy with Washington, and longed to get away from Secretary of State Edwin Stanton's oppressive scrutiny. Once Stanton and McClellan had mocked Lincoln together, but the Secretary had switched sides and, unlike his predecessor, he knew McClellan all too well. Paranoia was nothing new to McClellan's worldview, he always believed powerful forces were arrayed against him, but with Stanton at the War Department, for once, McClellan was right.

So McClellan was transferring the Army of the Potomac as quickly as he could to get to a place where he was the top officer in the theater (though the commander of Fort Monroe, the elderly Maj. General John Wool, was making even that a complex feat). Over 70,000 men in six divisions of the Army of the Potomac had already left through Alexandria. Two divisions (Fitz John Porter's and Charles Hamilton's) of Brig. General Sam Heintzelman's Third Corps were already fighting on the Virginia Peninsula, as was one (Baldy Smith's) of Brig. General Erasmus Keyes' Fourth Corps. Another of Keyes' divisions (Darius Couch's) was en route, along with the Reserve Division (Andrew Porter), most of the artillery and cavalry, and a division (John Sedgwick's) of Brig. General Edwin Sumner's Second Corps.

That left one division from the Fourth Corps (Silas Casey's), one from the Third Corps (Joe Hooker's), two from the Second Corps (Israel Richardson's and Louis Blenker's), and all three from Brig. General Irvin McDowell's the First Corps (William Franklin's, George McCall's, and Rufus King's). Casey's Division from the Fourth Corps was the next scheduled to depart, and, when it arrived, would make the first complete corps of the Army of the Potomac on the Peninsula, as well as mean McClellan had more divisions on the Peninsula than in Northern Virginia. So the commanding general had decided to depart with it and take command in the field, leaving it to others to embark all three divisions of McDowell's First Corps on April 2, followed by Hooker's division on April 7, and the remaining two divisions of Sumner's Second Corps some time in-between.

He would then have around 150,000 men to march on Richmond, one of the largest field armies in world history in 1862. The previous army marching on fixed positions on the Virginia Peninsula had been the coalition operation under George Washington and the Comte de Rochambeau, who had 5,500 men and 9,500 men, respectively. True, Napoleon had waged the War of the Second Coalition with an army of 200,000 men, but the geographic area he had covered had been several times the size of the Virginia Peninsula. For a modern comparison, at the height of the Iraq War surge in 2007, the United States had deployed 168,000 troops to Iraq, nation-wide, plus about 10,000 coalition troops in an area 160,000 square miles (counting Kuwait, where around 25,000 troops were in reality), which the CIA World Factbook unhelpfully describes as "slightly more than twice the size of Idaho". The entire state of Virginia is only 43,000 square miles, meaning that by the third week of April the Peninsula was going to have a population density close to a modern urban area.

Or that was McClellan's plan. On March 23, Confederate Maj. General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson had thrown the first wrench in it when he attacked in the Shenandoah Valley, against any reasonable expectation, and

diverted McClellan from transferring three brigades from there to Manassas Junction. That had slowed his departure schedule for the Second Corps, but there were plenty of other divisions to load in their place. It took Edwin Stanton to really derail McClellan's plans.

As McClellan readied all his baggage for transport, that blow was delivered by the President, though it is black with Stanton's fingerprints. "This morning I felt constrained to order Blenker's division to Fremont," Lincoln wrote in a note to McClellan.

I write this to assure you that I did so with great pain, understanding that you would wish otherwise. If you could know the full pressure of the case, I am confident you would justify it--even beyond the mere acknowledgement that the commander-in-chief may order what he pleases.

McClellan must have fumed. Fremont was Maj. General John C. Fremont, the Great Pathfinder who had been the first Republican nominee for president. Supporters praised him for winning California during the Mexican War, for treating the rebels with a firm hand, and for taking on the Slave Power in Missouri, by freeing the slaves of rebellious owners. Detractors saw the same events and criticized him for

filibustering to interfere with operations the Navy already had well in hand, brutally turning neutrals into Jeff Davis supporters, and acting unconstitutionally based only on the might of the men with guns who surrounded him. Lincoln had sacked Fremont, but the Radical Republicans in Congress, led by the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, had come dangerously close to attacking Lincoln himself and the President had made up a new command for Fremont.

Fremont was given the Mountain Department, a newly invented command between the ridge of the Appalachian Mountains and the Virginia [now West Virginia] that Lincoln may have vaguely hoped would lead to an invasion of loyalist East Tennessee. The small number of troops he would lead happened to be the same troops that McClellan had led pre-Bull Run, and his taking command would displace McClellan loyalist Brig. General

William Rosecrans. While that pleased the more radical members of Congress, they quickly understood Fremont had been stuck in an out-of-the-way corner and began demanding he be provided with troops. It was probably their ally Stanton that suggested sending Blenker's division, sitting idle at Warrenton Junction.

According to McClellan,

writing years later, Lincoln had visited him in Alexandria as much as a week earlier to view the progress of embarkation and to discuss the pressure to transfer Blenker.

A few days before sailing for Fort Monroe I met the President, by his appointment, on a steamer at Alexandria. He informed me that he was most strongly pressed to remove Blenker's German division from my command and assign it to Fremont, who had just been placed in command of the Mountain Department. He suggested several reasons against the proposed removal of the division, to all of which I assented. He then said that he had promised to talk to me about it, that he had fulfilled his promise, and that he would not deprive me of the division.

The reversal on the eve of his departure would turn out to be the first in a litany of wrongs McClellan would level against the Lincoln Administration for the eventual failure of the Peninsula Campaign, and which will still throw Civil War scholars into a tizzy trying to debate McClellan's legacy. At the time, though, McClellan took the news in stride. After stating his regret at the transfer, "first because they are excellent troops" (a controversial statement itself) and second "because I know they are warmly attached to me", McClellan assured Lincoln he understood. "I fully appreciate, however, the circumstances of the case, & hasten to assure you that I cheerfully acquiesce in your decision without any mental reservation."

In his memoirs, he would harshly scold Lincoln, saying "the commander-in-chief has no right to order what he pleases; he can only order what he is convinced is right. And the President had already assured me that he knew this thing to be wrong..." But in his reply at the time, he told Lincoln:

Recognizing implicitly as I ever do the plenitude of your power as Commander in Chief, I cannot but regard the tone of your note as in the highest degree complimentary to me, & as adding one more to the many proofs of personal regard you have so often honored me with.

Again, in his memoirs he warned the result of withdrawing Blenker would be catastrophic:

I replied that I regretted the order and could ill-afford to lose 10,000 troops who had been counted upon in arranging the plan of the campaign. In a conversation the same day I repeated this, and added my regret that any other than military considerations and necessities had been allowed to govern his decision.

And once again, his note to Lincoln said something quite different:

I shall do my best to use all the more activity to make up for the loss of this Division, & beg again to assure you that I will ever do my very best to carry out your views & support your interests in the same frank spirit you have always shown towards me.

Whichever was closer to McClellan's real attitude, he had to make the arrangements. So he sent a message to Blenker's corps commander, Edwin Sumner, who was at Warrenton Junction with Richardson's and Blenker's divisions after

chasing the Confederates back to the Rappahannock. Somehow the message got garbled and Sumner went ballistic. The normally reserved officer's reply seethes anger. In its entirety, it read:

I would respectfully ask to be informed what I am to understand by the withdrawal of the two principal divisions [Sedgwick's and Richardson's] from my army corps, and leaving me the German division only, which, in my opinion, is the least effective division in the whole army.

Sumner did not share McClellan's soft spot for the boisterous Eastern European troops (the "German" was often used as something of a epithet for non-Western Europeans, and Sumner certainly meant it that way), who only showed discipline (

or were disciplined, for that matter) during one of Louis Blenker's frequent parades. McClellan, who already had his hands full with the administration, was in no mood to deal with Sumner too. He wrote to him directly at ten til 9:00 in the evening, condescendingly explaining everything:

By order of the President Blenker's division is to join General Fremont. I shall replace it by a division under General Mansfield [to be created from troops stationed at Fort Monroe that were not McClellan's to command]. The purpose of withdrawing the two divisions of your corps is to concentrate your corps in the field of active operations under your personal command. You will receive further instructions tomorrow. In the mean time please have Richardson's division ready to move back in the morning.

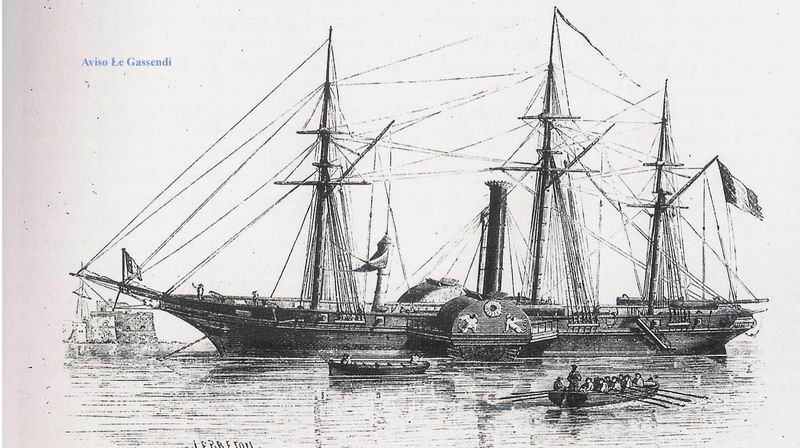

Sumner temper probably improved when he learned that he was accompanying Richardson to the Peninsula and not Blenker to the Valley and beyond. McClellan's probably did not improve, even as he joined his staff on the steamer

Commodore in Alexandria harbor on the morning of April 1. Before he could finally leave he had to settle the defense of Washington, to satisfy the terms the President had set before approving the Peninsula Campaign.

For McClellan it was a toss-up between two political generals to leave in charge of defending the capital. Brig. General James Wadsworth was the military governor of the District of Columbia and Maj. General Nathaniel Banks was the head of the fifth corps of the Army of the Potomac, currently commanding in the Valley. McClellan had more confidence in Banks, who he had worked with over the winter, and left the primary responsibility of defense to him.

Banks had six brigades grouped into two divisions to work with. One brigade, McClellan supposed (prematurely), was already at Warrenton Junction. A second was marching that direction and at White Planes. But McClellan had decided to rob from Wadsworth and ordered him to send a brigade of the troops within the District of Columbia's forts directly to Manassas Junction, and then two more brigade over the course of the next week. That would be nearly all of the (poorly trained) soldiers within the fortification line. Banks should move his remaining division to Staunton at the top of the Upper Valley, to control the fertile farmland down below.

Anticipating those orders going through, McClellan ordered Richardson's division to Alexandria and Blenker's to Strasburg. Then he

summarized everything for the War Department. There would be 7,780 men defending Warrenton, 10,859 at Manassas Junction, 35,467 based on Staunton in the Valley, and 1,350 replacing Hooker's Division in Charles County. A total of 55,456 men to defend the capital, plus about 18,000 men, he estimated, under Wadsworth within the fortifications of the District. McClellan probably did not realize how consequential the memo would become.

With everything completed, the steamer carrying McClellan finally pulled away from its moorings.

As soon as possible after reaching Alexandria I got the Commodore under weigh & "put off"--I did not feel safe until I could fairly see Alexandria behind us...I feared that if I remained at Alexandria I would be annoyed very much & perhaps be sent for from Washn. Officially speaking, I feel very glad to get away from that sink of iniquity...

But he had not gotten away. Not in the least.

Print Sources: