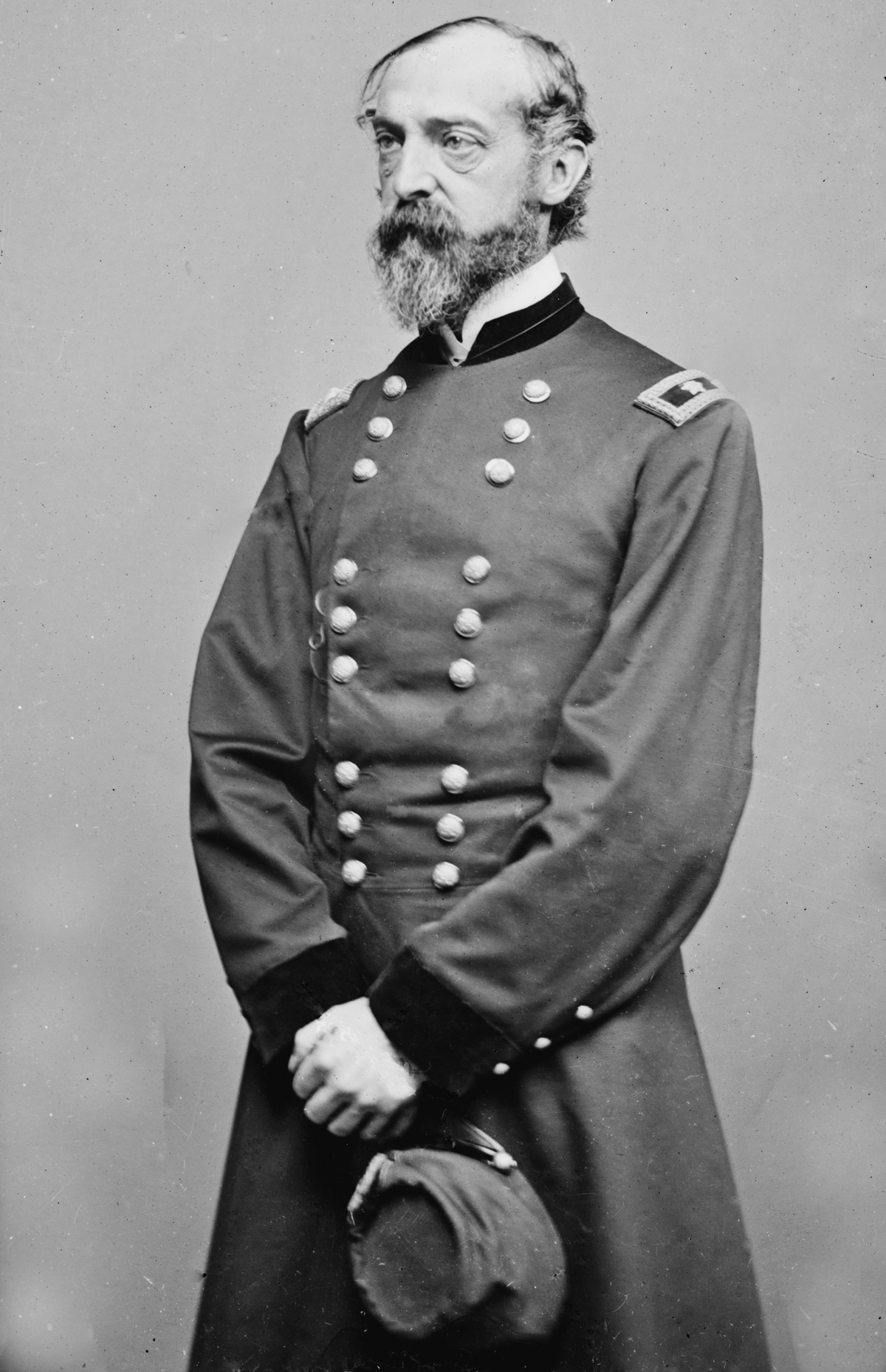

Wherein we make the acquaintance of the general everyone thinks they know

..............................................................................................................................

|

| George Gordon Meade |

By 1865, Meade would be a household name, but in 1861 that an obscure army officer could have one of the most sought after positions in the Northern states - command of a brigade in George McClellan's assembling Army of the Potomac - was somewhat astounding. That it was not just any army officer, but the notoriously difficult George Meade was even more astounding.

Meade had graduated from West Point in 1836, three years before G.T. Beauregard and a decade before McClellan. He had ranked 19th out of 56, securing him one of the last slots for artillery in his graduating class and saving him the indignity of going into the infantry. Not that Meade particularly cared, since he had never wanted to attend West Point in the first place.

The troubles that led to Meade's military career were really Napoleon Bonaparte's fault. Meade's father, Richard, was the scion of a wealthy Philadelphia merchant family and making a killing managing his family's foreign transactions in Spain. Living in Cadiz, Richard purchased a fine house and secured a post as U.S. naval agent for the port, in charge of promoting American business and trade. In 1808, Richard's royal friends were treated to a rude surprise when their ally Napoleon invaded and overthrew their government. Richard backed the Royals with his fortune, supporting the resistance to the French.

With Napoleon defeated and the monarchy restored in 1812, Richard Meade was offered Spanish citizenship (he declined), but not reimbursement of his loans (he sued). The Spanish government responded with accusations that Richard had improperly steered contracts and outright cheated it during the war, and pressed charges. It was during this time, on the final day of 1815, that the Meade's eighth child, George Gordon, was born. Not long afterwards, Richard was thrown in prison to keep him away from already cantankerous Spanish republicans.

Young George and his mother moved to Philadelphia by 1817, and she worked hard to get the American government to intervene. Andrew Jackson's invasion of Florida in 1818 secured Richard's release, through the complex machinations that only international relations can yield. In 1819, the Adams-Onis Treaty ended what Jackson had started, and ceded present-day Florida, and coastal Mississippi and Alabama to the United States. But it also included a clause sticking the United States with all outstanding claims by Americans against Spain. So Richard moved his family to Georgetown to lobby the Federal government for his lost fortune.

Young George was shipped off to an expensive boarding school in Philadelphia, where he thrived and learned the classics. But Richard's remaining wealth was rapidly disappearing due to legal fees, and his health was deteriorating almost as quickly. In 1828 he died and the family's finances collapsed. George was recalled to Georgetown, and tried a boarding school in Washington and one in Baltimore, before his mother hit on the idea of West Point. Someone had told Mrs. Meade that a West Point graduate could do anything. She failed in her 1830 campaign, but returning wiser in 1831 she got him into his top-notch education at the expense of the U.S. government.

So when George Meade graduated in 1835, it was with the intention of leaving the Army as quickly as possible. As fortune would have it, his first assignment was with the 3rd Artillery in Florida, fighting the Seminole for the land whose acquisition had played a major role in bankrupting his father. He contracted a severe illness pretty quickly and was transferred to escorting captured Seminole on their relocation march, but within a year he was gone from the Army.

Meade moved onto a career that he really wanted: engineering. In a tradition that continues today, the Army hired the recently discharged Meade as a civilian contractor to survey boundary lines, including the boundary with Canada. With more flexibility than in military life, Meade went to visit his mother more frequently in Washington, and began courting the daughter of a Congressman John Sergeant of Philadelphia, who had unsuccessfully tried to help the family receive recompense. Meade married Margaretta Sergeant on his 25th birthday in Philadelphia (Margaretta's sister married Henry Wise one month earlier).

In 1842, Meade used the help of Wise (now a Congressman) to rejoin the Army as a Second Lieutenant in the Engineers, since the contracting gigs were drying up. The next year, he was off boundary lines and instead constructing lighthouses in the Delaware Bay, including the famous Brandywine Shoal Light. He also had time to have three kids with Margaretta, including his pride and joy, his eldest son John Sergeant Meade, named after his father-in-law, but called Sergeant with the family.

When trouble began brewing on the border between Texas and Mexico, Meade was sent to the general in charge there, Zachary Taylor. Throughout Taylor's campaigns, Meade scouted marching routes and acted as a guide during battles, often as the only engineer present due to disease and bullets. But in a story that would recur throughout his life, others got credit and promotion while Meade was overlooked. After a particularly difficult feat of guidance in the Battle of Monterrey, he finally received a brevet to First Lieutenant.

Meade was transferred along with most of the Regulars to Winfield Scott's army marching from Vera Cruz to Mexico City, but found himself irrelevant because of the special corps of engineers Scott had brought with him (including McClellan, Beauregard, and Robert E. Lee). When he complained to a commanding officer, he was sent back to headquarters in Washington. The war was over for him and it was back to lighthouses.

For the next nine years Meade worked almost non-stop on lighthouses on the coasts of Florida, New Jersey, and Delaware. In that time he received only two promotions, reaching the rank of captain in 1856, along with a transfer to supervise a survey of the Great Lakes. And Detroit is where he and Margaretta were when Beauregard commenced firing on Fort Sumter.

On April 20, the day after the violent Baltimore riots, the Republican leaders that had swept into power in Detroit asked all officials to swear an oath of loyalty to the Union in front of an assembled mass of citizens. Meade was indignant, since he had sworn an oath when joining the army (twice, in fact) and assembled his tiny staff to declare that he would never swear an oath mandated by politicians. They agreed and Meade sent a message back that they would only take such action if ordered by the War Department. This infuriated the elected officials, including Michigan Senator Zachariah Chandler.

The spring turned into summer, the Northern forces were clobbered at Bull Run, and one-by-one all of Meade's subordinates went off to new commands (two of them to the Confederacy). But Meade remained, sunk by both a vindictive U.S. Senator and a career without enough awards from battle. A political power in her own right, Margaretta went to work trying to counter Chandler's influence in Washington, and in mid-summer, McClellan sent for Meade to join the corps of topographical engineers he was creating for his professional, European-style staff.

So Meade was stunned to arrive in Washington and find that McClellan had changed his mind and was having him made a brigadier general of volunteers. Pennsylvania Senator David Wilmot and Pennsylvania governor Andrew Curtin had responded to the pleas of John Sergeant's daughter. And so Meade found himself commanding the 3rd, 4th, and 7th Pennsylvania Reserve Regiments (returned from picket duty at Great Falls) - he would soon add the 11th as well.

Meade was treated with a friendly suspicion by the line officers, who acknowledged his brilliance but were unsure about his ability to fight. Still, he liked the position. "I find camp life agrees with me," he wrote Margaretta,"and the active duties I have entered on are quite agreeable."

Meade is matter-of-fact in his writing, describing minutia and asking about friends and family. But he clearly respects his wife as his most trusted adviser, and doesn't withhold his thoughts from her or attempt to aggrandize himself (like McClellan). With no melodrama, only simple honesty, he wrote her in his September 22 letter:

Sometimes I have a little sinking at the heart, when I reflect that perhaps I may fail at the grand scratch; but I try to console myself with the belief that I shall probably do as well as most of my neighbors, and that your firm faith must be founded on some reasonable groundwork.

It was the first letter Meade had written since Margaretta had returned to Philadelphia. She and Sergeant had traveled with Meade to help him get set up, and he lamented in his letter that they had missed the grand review by the Prince de Joinville (who was still kicking around Washington, being entertained in high style by McClellan). With such a turbulent childhood, Meade loved the stable family life he and Margaretta had created. But he recognized that in the Mexican War he had missed out on opportunity for an advancement that could secure his family's comfort, and his improbable second chance couldn't be passed up.

I felt very sad when you drove off, and could hardly shake off the idea that I was looking on you perhaps the last time--at any rate, for a long while; but I trust matters will be more favorable to us, and that it will please a just and merciful Providence to permit us to be happy once more, united, and free from immediate trouble.

Print Sources:

- Sauers, 3-16.

No comments:

Post a Comment