Wherein the old boy gets his second wind

........................................................................................................................

|

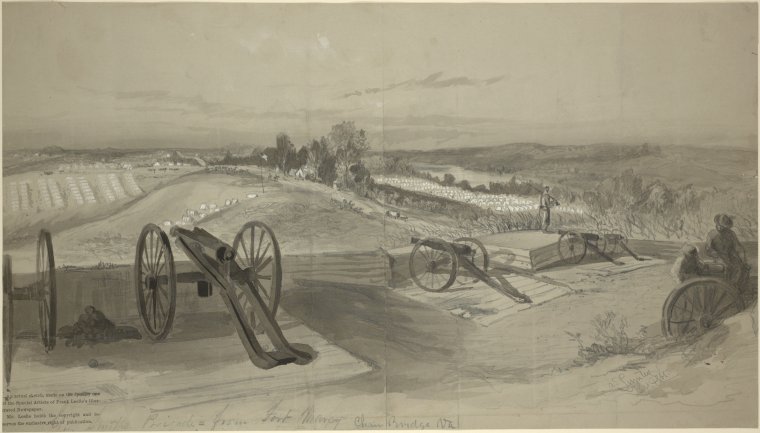

| View from Ft. Marcy, completed in late September 1861 by W.F. "Baldy" Smith's brigade |

On September 16, George McClellan got an order transmitted by Lt. Colonel Edward Townsend, chief of staff for the general-in-chief of the U.S. Army, Winfield Scott.

The commanding general of the Army of the Potomac will cause the position, state, and number of troops under him to be reported at once to general headquarters, by divisions, brigades, and independent regiments or detachments, which general report will be followed by reports of new troops as they arrive, with the dispositions made of them, together with all the material changes which may take place in said army."By command of Lieutenant-General Scott," Townsend helpfully signed it, opting for a more military valediction than his typical "your obedient servant". Winfield Scott was at last striking back.

Almost since McClellan had arrived in Washington (and certainly since Scott had poo-pooed his intelligence that an attack by over 100,000 Confederates was imminent), the junior general had attempted to circumvent the elderly general-in-chief. He had decided that Scott had become too senile or too stuck in his ways to take the bold actions needed to save the Union. And Scott was affecting a cadre of senior officers from the old Army. Only by breaking the stranglehold of the same military leaders that had let the South secede, take Federal property, and win at Bull Run and Wilson's Creek, could McClellan save the Union.

Since Lincoln had been unwilling to accept Scott's request to be retired, McClellan had hit upon a new strategy: simply ignore the Army's top officer. He sent him no unit status reports, no supply or acquisition reports, and no report on the new divisions he was organizing. In fact, the very day McClellan received Scott's order he was in the process of creating a new division out of the Pennsylvania Reserves.

McClellan had taken almost two weeks off from creating divisions after the uproar he had caused among those very same old officers he was trying to circumvent by promoting their juniors to division command. While Sam Heintzelman, David Hunter, and Erasmus Keyes, the top-three brigadier generals of volunteers on the list, sat commanding brigades, McClellan favorites William Franklin and Fitz John Porter were elevated to command divisions. Not only that, but Little Mac in early September had added a third brigade (Dan Butterfield's) to Porter's, which meant that both he and Franklin commanded units equal to the size of Nathaniel P. Banks, who was a major general of volunteers. The old guard turned green.

On September 12, McClellan made them greener by elevating Charles P. Stone, number eight on the list, to divisional command, sending him a second brigade to join his own for the mission of securing the fords around Leesburg. Two days later, McClellan tapped his good friend Don Carlos Buell (number nine) to head another. Buell had been bound for Missouri, to help Maj. General John C. Fremont organize a Union army there to deal with the growing violence, but a surly reply from McClellan to Secretary of War Simon Cameron had changed his orders. Since he didn't have his own brigade, McClellan gave him those of Darius Couch and Lawrence Graham to lead.

And finally, on September 16, McClellan had elevated number 13, George McCall, and made his Pennsylvania Reserves into a division (the in-between generals on the list were outside of McClellan's jurisdiction: No. 10, Thomas Sherman, and No. 12, John Pope, were in the West and No. 11, Nathaniel Lyon, was dead). McCall's promotion was less part of McClellan's scheme/cronyism, because Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin had insisted to the War Department that 13 regiments of the Reserves fight as one unit, and that was way too many men for a single brigade.

McClellan, however, was starting to run low on hand-picked subordinates, and Curtin's further insistence that the brigade commanders be Pennsylvanians was also making things harder. Fortunately, the same petulant letter to Cameron that had brought Buell back, brought back John F. Reynolds. McClellan put the dashing young Pennsylvanian in charge of one of the three brigades. McClellan found another Pennsylvania brigade commander in George Meade, who had been about ready to take up a post as an engineer on McClellan's staff. But the third brigade would have to operate under a colonel until McClellan could find another suitable general officer to lead it (it would take a month to settle on Brig. General Edward O.C. Ord).

Winfield Scott knew all this, of course. With McClellan ruffling so many feathers, he got daily reports from everyone on all the comings and goings of the forming Army of the Potomac. But the point was to make McClellan acknowledge his place in the chain of command, and requiring him to submit regular reports on the organization process would force him to acknowledge that. And if he didn't it gave Scott an opportunity to appeal to military law to punish McClellan, and force him to acknowledge his subordinate status that way.

McClellan, meanwhile, was trying to control one of his less-favored subordinates. His first two division commanders had been consolations to the Lincoln Administration for political reasons: Brig. General Irvin McDowell, so that no one would have to say it had been a mistake in judgment putting him in charge for Bull Run, and Maj. General Nathaniel P. Banks, a prominent politician who had been the first Republican Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. Banks was the problem. After meeting with McClellan on September 14 in Rockville (when McClellan informed Stone he would lead a division and they discussed plans for defending against the inevitable Confederate attack from Leesburg), Banks had been unhappy with McClellan's attentiveness to the size and equipment of his division. So he had mailed his friend William Seward, the Secretary of State.

On the 16th, McClellan sent him assurance that his supplies were on the way, while chastising him that "you forget that the present duty of your division is simply to support the division of Genl Stone in opposing any attempt of the enemy to cross the River..." He also added, lest Banks draw the wrong conclusions:

It may be well for me to state that these measures are taken in consequences of what passed at our interview of Saturday [September 14] & are not brought about by your letter to the Hon Secty of State. If you will fully communicate your wants direct to me through the proper military channel you will find that they will meet the most prompt attention possible, as I feel the same interest in the efficiency of your division that I do in any other portion of the Army under my command...Winfield Scott, who was notified both of Banks' circumvention and of McClellan's reply (possibly from Banks) seized the opportunity to take another swipe at McClellan, who regularly made requests of the Secretary of War outside of the proper military channels. Scott had Edward Townsend issue an army-wide order from his headquarters (General Order No. 17), ostensibly responding to Banks' breach.

There are irregularities in the correspondence of the army which need prompt correction. It is highly important that junior officers on duty be not permitted to correspond with the general in chief, or other commander, on current official business, except through intermediate commanders ; and the same rule applies to correspondence with the President direct, or with him through the Secretary of War, unless it be by the special invitation or request of the President.

By command of Lieutenant-General Scott

Print Sources:

- Sears, 101-102.

No comments:

Post a Comment