In which it becomes apparent the author has read too many McClellan letters

..................................................................................................................................

|

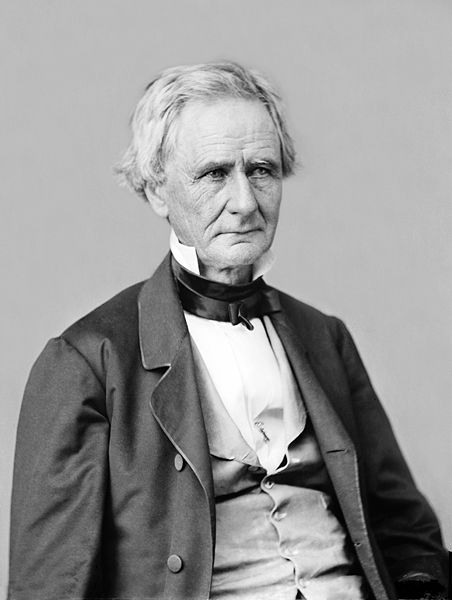

| Secretary of War Simon Cameron |

On September 7, Cameron decided the best way to make amends in the Union high command was to assuage McClellan's paranoia about a lack of support from the Lincoln Administration and the War Department. Assured, the younger general would then be able to give Scott the deference the older man thought he deserved. So he sent McClellan a carefully crafted note.

It is evident that we are on the eve of a great battle--one that may decide the fate of the country. Its success must depend on you, and the means that may be placed at your disposal. Impressed with this belief, and anxious to aid you with all the powers of my Department, I will be glad if you will inform me how I can do so.Cameron was surely pleased with his little bit of diplomacy. It gave credence to McClellan's obsessive insistence that the Confederates were on the verge of attacking (which Scott continued to ridicule) and signaled that the War Department was eager to give McClellan what he felt he needed.

As with all things McClellan, it went horribly awry. "Your note of yesterday is received," the general replied on September 8 from his headquarters at 19th and H, NW. "I concur in your views as to the exigency of the present occasion. I appreciate and cordially thank you for your offers of support and will avail myself of them to the fullest extent demanded by the interests of the Country."

McClellan started with a quick assessment of his own troops (85,000 immediately around Washington, plus the divisions of Nathaniel P. Banks close to Harper's Ferry and Charles P. Stone at Poolesville). Then he started his bold claims.

It is well understood that although the ultimate design of the enemy is to possess himself of the City of Washington, his first efforts will probably be directed towards Baltimore, with the intention of cutting our line of communications and supplies as well as to arouse an insurrection in Maryland.While certainly not out of the realm of possibility, this analysis was far from "well understood." For one, marching on Baltimore to cut off Washington's line of supplies would make Joe Johnston's Confederate army around Manassas even more completely cut off from their own line of supplies. At least Washington would have the C&O Canal to move supplies down from Harper's Ferry, Johnston would have McClellan's force of at least 85,000 men between him and any supplies in that scenario.

But McClellan went on, explaining that Johnston would "no doubt show a certain portion of his force in front of our positions on the other side of the Potomac" as a distraction and make demonstrations (small attacks and artillery bombardments) at Aquia Creek, Mathias Point (near Dahlgren Naval Surface Warfare Center), and Occoquan to further dilute McClellan's army. "His main and real movement will doubtless be, to cross the Potomac between Washington and Point of Rocks, probably not far from Seneca Falls, and most likely at more points than one." In other words, the nightmare scenario envisioned by Charles P. Stone for Johnston's crossing during the Rockville Expedition.

It would be easy for Johnston to do this, McClellan explained.

I see no reason to doubt the possibility of his attempting this with a column of at least one hundred thousand effective troops; if he has only one hundred and thirty thousand under arms, he can make all the diversions I have mentioned with his raw and badly armed troops, leaving one hundred thousand effective men for his real movement. As I am now situated, I can by no possibility bring to bear against this column more than seventy thousand and probably not over sixty thousand effective troops.It was a complete vindication of Winfield Scott's complaints about McClellan. Johnston would have been lucky to have had 50,000 effective troops in his army around Manassas Junction, closer to the old general's estimates. Historically, we have the benefit of knowing that not only would the Confederacy never field an army that large, but neither would the Union (the closest it got was 125,000 men in the combined Armies of the Potomac and James during the Appomattox Campaign). But McClellan didn't really believe that Johnston had 130,000 men to his own 85,000.

In making the foregoing estimate of numbers I have reduced the enemy's force below what is regarded by the War Department and other official circles as its real strength, and have taken the reverse course as to our own.This would have been news to Cameron, whose War Department said no such thing.

To render success possible, the Divisions of our Army must be more ably led and commanded, than those of the enemy. The fate of the nation and the success of the cause in which we are engaged, must be mainly decided by the issue of the next battle, to be fought by the army now under my command. I therefore feel, that the interests of the nation demand that the ablest soldiers in the Service should be on duty with the Army of the Potomac, and that contenting ourselves with remaining on the defensive for the present at all other points, this Army should be reinforced at once, by all the disposable troops that the East and West and North can furnish.McClellan was nothing, if not consistent. He maintained his belief that the war would be decided in a great battle, like Austerlitz, the battle at which, after a campaign of a mere four months, Napoleon defeated and subjugated the empires of Austria and Russia. Therefore every division or brigade commander, and every additional soldier, horse, or gun, could make the difference. It was not Scott's Anaconda Plan, which relied on the gradual wearing down of the Southern capacity to wage war ("attrition").

Specifically, McClellan needed the U.S. Army regulars, the professional soldiers that, under Scott's recommendation, were mostly scattered around the frontier continuing to do the jobs they had done before the war, with a few small groups mixed into the growing volunteer armies, largely to keep order. "Scattered as the regulars now are, they are nowhere strong enough to produce a marked effect; united in one body, they will ensure the success of the Army."

And to address individuals, he took aim at Scott's habit of pushing favored subordinates on him.

In organizing the Army of the Potomac, I have selected General and Staff Officers with distinct reference to their fitness for the important duties that may devolve upon them. Any change or disposition of such officers, without consulting the Commanding General, may fatally impair the efficiency of this Army and the success of its operations. I therefore earnestly request, that in future every General Officer appointed upon my recommendation shall be assigned to this Army; that I shall have full control of the officers and troops within this Department; and that no orders shall be given respecting my command, without my being first consulted.As far as staffing went, commanding generals had always been given leniency in choosing their own. McClellan's assertion that he have complete control over choosing his subordinate generals was also a time-honored tradition (Scott had thrown fits about it almost his whole career), but it was also a time-honored tradition for the civilian leadership to ignore them and appoint whoever was politically expedient to almost any battlefield position.

McClellan took the opportunity to name two of the brigadier generals of volunteers he had recommended, Don Carlos Buell and John F. Reynolds. Buell had been helping McClellan organize the Army and his staff, but Scott had persuaded the War Department to send him West to help organize (and control) Maj. General John C. Fremont. Reynolds had gone West already to lead the 14th Infantry Regiment (since its nominal colonel, Charles P. Stone, was leading a brigade for McClellan) on the frontier. McClellan intervened to have him made a brigadier general of volunteers and recalled to Washington, but Scott had diverted him en route to order him to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, where Maj. General Benjamin Butler had carried out a successful amphibious assault and now was in over his head.

"I respectfully insist," McClellan wrote, "that Brigadier Generals Don Carlos Buell and J F Reynolds, both appointed upon my recommendation and for the purpose of serving with me, be at once so assigned."

He closed:

In obedience to your request I have thus frankly stated "in what manner you can at present aid me in the performance of the great duty committed to my charge," and I shall continue to communicate with you in the same spirit.

Very respectfully Your Obt ServtGeo B McClellanMaj Genl Comdg

No comments:

Post a Comment