Wherein George Meade shares his personal thoughts on the war

............................................................................................................................................

Happy Thanksgiving everyone. In 1861, Thanksgiving was not a Federal holiday, but was still widely celebrated in America in November. But we're not commemorating the 150th Anniversary of that today, because the dates didn't line up that way.

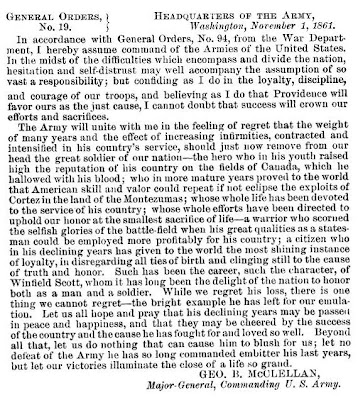

Instead, recognizing everyone is busy, including me, here's a letter from George Meade to his wife sharing his thought on the war from Fall 1861:

Camp Pierpont, Va

November 24, 1861

There is but little new here. My duties at the court occupy me nearly all day, and in the afternoon, towards evening, I take a ride through the guards to see that they are on the alert and vigilant. The enemy do not show themselves nearer than eight miles, where they have their pickets. Now and then they make a dash at some part of the line with their cavalry, and drive ours in, killing and wounding a few, when they retire again to their old lines.

In today's papers we have Jeff Davis's report to the Confederate Congress. A careful perusal of it leads me to think it is more desponding and not so braggadocio a document as those we have hitherto had from him. I have no doubt the blockade and the heavy expenditures required to maintain their large armies are telling on them, and that sensible people among them are beginning to say "cui bono," and where is this to end? If such should be the case, it proves the sagacity of our policy in keeping them hemmed in by land and sea, and forcing them to raise large forces by threatening them at many different points. You know I have always told you this would be a war of dollars and cents, that is, of resources, and that if the North managed properly the South ought to be first exhausted and first to feel the ruinous effects of war. In other words, to use my familiar expression, it was and is a Kilkenny cat business, in which the North, being the biggest cat and having the largest tail, ought to have the endurance to maintain the contest after the Southern gentleman was all gone. In the meantime, we at the North should continue the good work of setting aside such men as Fremont, and upholding such sentiments as those of Sherman, who declares the private property of Secessionists must be respected. Let the ultras on both sides be repudiated, and the masses of conservative and moderate men may compromise and settle the difficulty.

Today has been raw and disagreeable; this afternoon we had a slight spit of snow. Camping out in such weather is very hard upon the men and the health of the army is being seriously impaired. I fear no amount of personal energy or efforts to do what is right will ever make these volunteers into soldiers. The radical error is in their organization and the election of officers, in most cases more ignorant than the men. It is most unsatisfactory and trying to find all your efforts unsuccessful, and the consciousness of knowing that matters grow daily worse instead of better is very hard to bear. The men are good material, and with good officers might readily be moulded into soldiers, but the officers as a rule, with but very few exceptions, are ignorant inefficient and worthless. They have not control or command over the men, and, if they had, they do not know what to do with them. We have been weeding out some of the worst, but owing to the vicious system of electing successors which prevails, those who take their places are no better. I ought not perhaps to write this to you, and you must understand it is all in confidence, but you have asked me to tell you everything freely and without disguise, and I have complied with your request.

I had a visit to day from Mr Henry of the Topographical Bureau, who says he saw the review on Wednesday and thought our division looked and marched the best of all.