Wherein not every general is off to a new adventure

............................................................................................................................................

On March 17, the Third Division of the Third Corps became the first part of the Army of the Potomac to load on transports and depart for a grand campaign to capture Richmond. The First Division, Third Corps was scheduled to follow it in just a few days, when the transports returned, and begin expanding the beachhead on the Virginia Peninsula so that Maj. General George McClellan could land his army of over 150,000 men--an army twice the size of the one Napoleon had commanded for his great victory at Austerlitz.

But it was more than just transports that delayed McClellan's relocation of his base of operations (the place from which an army in the field supplies and sustains itself). President Abraham Lincoln had dictated that McClellan could not make the move without guaranteeing the safety of the capital, and so McClellan had dispatched the corps commander he had the most confidence in to ensure the Confederates were really gone.

|

| Alexander and Duffey's handiwork, March 1862. The former bridge over Bull Run on Warrenton Turnpike |

I was directed to blow up the old Stone Bridge--an arch of about 20 feet--when all had crossed, & Maj. Duffey & I mined the abutments & loaded them, & then the major remained & fired the mines at the proper time. I have always wanted to revisit that spot, which was quite a pretty one in those days, but I never had the chance, though I went across Sudley Ford, only two or three miles off, in Sept. '62. I will probably never see it again, but if any of my kids, or kid's kids, ever travel that Warrenton Pike across Bull Run they may imagine Maj. Duffey & myself, on a raft underneath the bridge mining holes in the abutments, & loading them with 500 lbs. of gunpowder & fixing fuses on hanging planks to blow up both sides simultaneously.

The man being delayed by Alexander and similar Confederate demolitions teams was Brig. General Edwin Vose Sumner. Sumner, it was widely agreed, was born to lead men in battle. Of all the corps commanders, he was the one who McClellan was the least concerned about. Sure he might not have First Corps commander Maj. General Irvin McDowell's raw intellectual power (of which McClellan was skeptical, anyway), but he had years of experience leading troops in battle in Mexico and on the American frontier. And so he had been left behind at Manassas Junction while the rest of the army moved to Alexandria to make sure the Confederates were really gone.

Sumner had led his division (before corps orders went into effect) into Manassas Junction the day after McDowell and McClellan had visited it, and kept up a pursuit of the Confederates with a small command of two cavalry regiments and a handful of infantry. Through driving rain, they followed the railroad from Manassas Junction to Catlett's Station, then crossed Cedar Run and moved towards Warrenton Junction [Calverton]. It was there that he had run into the rear guard of the retreating Confederate army, and turned back to report his findings to Sumner.

The next day had been March 17, the day of the first departure for the Peninsula, but with the Confederates still on the north bank of the Rappahannock, McClellan couldn't say that he had satisfied the requirement that the capital was safe. Nevertheless, he was already moving ahead with plans to move the Army of the Potomac away. Sumner's Second Corps was going to have to clear the Confederate army over the river.

Sumner's division had passed to Brig. General Israel B. Richardson, a highly respected, though somewhat eccentric general known as "Greasy Dick" to his friends. Richardson had encountered some trouble at Blackburn Ford just before the Battle of Bull Run, but had avoided the stigma that attached itself to many of the commanding officers over their parts in the battle. He had commanded a brigade at that battle that included the 2nd Michigan Infantry Regiment (which later was responsible for sacking Pohick Church) he had helped raise and its sister regiment, the 3rd Michigan, as well as two others. After being elevated to brigadier general of volunteers, he had kept both Michigan regiments and added the 5th Michigan, as well as a New York regiment, to become the senior brigade in Heintzelman's old division. But just four days before his brigade was to board transports for the Peninsula, Richardson was asked to replace Sumner when he moved up to corps command, and so his men left for the great adventure without him.

Richardson was self-confident enough not to mind that Sumner for all practical purposes was a second division commander. His other two divisions--Louis Blenker's predominant German and Eastern European division, and Charles P. Stone's old division, now led by John Sedgwick--were temporarily reporting to Maj. General Nathaniel P. Banks in the Shenandoah Valley, as he drove Stonewall Jackson south.

On March 20, Sumner had Richardson send a brigade down the Warrenton Turnpike [US29] to Gainesville, the last station along the Manassas Gap Railroad before Manassas Junction. The railroad continued out to Strasburg, in the Shenandoah Valley, which one of Banks' divisions was supposed to be occupying and where Blenker might be able to embark his division to move it more rapidly to join the rest of Sumner's corps (and by which Banks could eventually replace Sumner as the garrison commander at Manassas Junction). But if Banks had not seizes Strasburg, Gainesville could also be a debarkation point for Jackson's men to surprise Manassas Junction and capture Richardson's division.

|

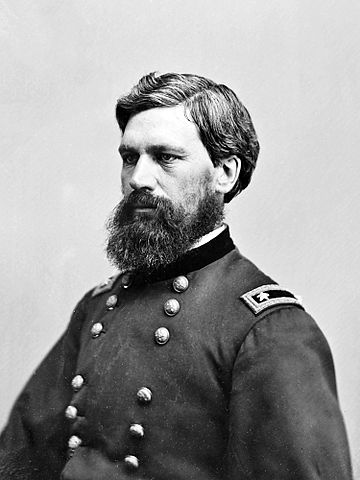

| Brig. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard |

As a Maine militia colonel for that state's 3rd infantry regiment, Howard had only had about seven weeks to train them before they began their march on the Confederate position behind Bull Run. For part of that time, Howard had also served as commander of a brigade. He had done his best on top of Henry Hill, almost winning the day as the last reserves. Instead, he had kept together a core group of his brigade to limp back to Alexandria that night.

Like Richardson, Howard's reputation had survived the battle, and he had soon found himself a brigadier general of volunteers, transferred to Sumner's Division as his senior brigade commander. So on March 20, three days after his old regiment, the 3rd Maine, had departed Alexandria as part of the Third Division, Third Corps, Howard took three squadrons of cavalry (six companies) and Colonel James Miller's 81st Pennsylvania to reconnaissance the Manassas Gap Railroad.

The only way for Sumner to know if there were Confederates at Gainesville was to move some of his own men there and see what shot at them. Had he used cavalry only, Confederate cavalry or a small detachment of infantry would be enough to create a screen, a collection of troops that made passing beyond a certain point impossible. Howard was moving with enough force to drive away any Confederate cavalry and infantry up to a regiment in size. If it turned out that there were more Confederates than that, Sumner would have much bigger problems.

Amid a day of moderate rain, Howard confirmed that the Confederates were gone from Gainesville.

I proceeded carefully to Gainesville... We found that the enemy had burned up tents and other camp equipage at different points. At Gainesville the depot is burned... We had it from pretty good authority that the bridges at Thoroughfare [Gap] and across the Shenandoah River had been burned.The burned bridges news was a particularly reassuring bit of intelligence. It meant that Jackson was not traveling from the Valley to surprise Sumner. Better yet, Howard was pretty sure that he hadn't already traveled that way either.

I feel assured from my scouting yesterday and today that there is no sign of the enemy having been north of the Manassas Gap Railroad for the last four days, and that General Jackson did not retreat by this railroad.But where were the Confederates that had retreated from Manassas? Howard had found some of them too.

"The pickets of the enemy are beyond New Baltimore, on the Warrenton turnpike [US29]," he said, which combined with the findings of the cavalry expedition from earlier that week seemed to confirm that they were retreating, albeit slowly. They also appeared to be in bad shape, judging by the trail left by Confederate cavalier Jeb Stuart: "General Stuart passed through Gainesville on his retreat. His horses are said to be in bad condition. We found dead horses all along our route."

But while Howard and Richardson were making the most of their time not headed to the Peninsula by gathering valuable intelligence over near Dumfries another of the left behind wasn't nearly so gracious. The 1st New Jersey Cavalry wasn't even supposed to be part of the Union army. Shortly after Bull Run, then-Secretary of War Simon Cameron had granted William Halstead, a politician from New Jersey with whom he might have had some shady dealings, the right to command a cavalry regiment among the U.S. Volunteers. The only problem was that the New Jersey legislature had not approved the raising of such regiment.

Halstead raised them anyway, but New Jersey refused to recognize them, and so the regiment had existed in a sort of limbo where it was known as the Halstead Horse, and found itself attached to Heintzelman's old division. Halstead proved to be a particularly poor commander, and ended up spending more time catching up with former friends from his four non-consecutive years in the House of Representatives than with his men. When his lieutenant colonel tried to fill the leadership gap, Halstead ignited a feud that split the regiment and led to horrible discipline, which was only solved when Halstead was arrested by the War Department's new head, Edwin Stanton. Halstead was released in January, and promptly arrested his lieutenant colonel and the major who had helped them, and the whole thing fell apart again.

The War Department finally solved the whole matter by ejecting Halstead from the army as unfit for command, which led New Jersey to finally authorize the regiment as its 1st Cavalry. McClellan--as he was prone to--had become taken with a European officer who had volunteered for service in the Union army, and recommended that Sir Percy Wyndham be named the new colonel.

|

| Colonel Percy Wyndham |

Their king, Vittorio Emmanuale II, had knighted Wyndham, but he was already off on his next adventure: the American Civil War. Wyndham, with a famously ridiculous mustache even in an era of ridiculous facial hair, got the regiment back into shape again. As the colorful history of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry recorded:

Under the active superintendence of the three soldiers now at its head, drill went actively on. Everything superfluous in the clothing and equipment of the troopers was taken away, and every deficiency carefully supplied. Several times the regiment was ordered out, as if for the march, until the men became accustomed to pack and saddle well and promptly. The regiment was perhaps more perfectly prepared for the field than any other in the army, when, to its dismay, McClellan moved leaving it behind.McClellan had certainly not considered it more perfectly prepared for the field than any other in the army, and so had detached it from Heintzelman's old division and assigned it to the new Military District of Washington, to be commanded by another left behind soldier, Brig. General James Wadsworth. Technically, Wadsworth hadn't been left behind yet, since his brigade had been part of McDowell's First Corps, which wasn't slated to leave for almost a month, but it had already been given to someone else.

A relative of the famous New York and New England family of the same name, Wadsworth had been a volunteer aide-de-camp to McDowell at Bull Run, and was one of the few brigade commanders not hand-picked by McClellan (the commanding general had actually opposed his promotion). His connections and McClellan's disinterest in taking him to the Peninsula, had resulted in his naming as military governor--a colossal political blunder on McClellan's part. Wadsworth hadn't quite put all the pieces together yet, but McClellan was planning on gradually leaving him with all the least regarded regiments of the army, like the 1st New Jersey Cavalry.

"The colonel consoled himself by going out to sweep the country in the direction of Dumfries, picking up straggling scouting parties of the enemy," the regimental history recorded about Percy Wyndham's response to being left off the boats of March 17. "There was enough show of danger to make the work exciting and to give a sensation of success and a feeling of enterprize [sic]; so that these expeditions were of great value in their effect upon the men."

The history overstates the value of the raids. On March 20, while Otis Howard did valuable reconnaissance work, Wyndham sent his third battalion under Major Ivins Jones on what was little more than a looting romp. Jones and his New Jersey horsemen took Telegraph Road to Dumfries, passing through the camps of four brigades, in his estimate (Confederate Brig. General W.H.C. Whiting would have been ecstatic to have four full regiments at Dumfries). "Considerable numbers of tents were left in the camps," he reported, "but they were old and worthless." Apparently not worth bringing back.

His report continues, itemizing items to loot or already looted.

I counted thirty-two large Confederate army wagons, which were mostly in good condition, and had been left by the rebels on account of the scarcity of horses and almost impassable conditions of the roads. I ascertained that the rebels had two trains of pack mules. I also found considerable flour and hard bread, which had been taken from the camps by the farmers and is still in their possession, as I had no transportation.]He continues:

On the farm of a Mr. Weaton, on the Brentsville road, is a large quantity of officers' baggage belonging to General Whiting's brigade. In fact, in the vicinity at almost every farm there is something concealed. I have reliable information that in the vicinity of Bacon Race Church there is a large quantity of stores, among which is a quantity of hospital stores. At Neabsco Mills I found an ambulance, which was said to have been taken from our troops at Bull Run.He even notes the possibilities for expanding the regiments operations: "There is considerable grain in this vicinity, but little or no hay. The nature of the roads would not allow a baggage train to bring away any quantity of stores just at present."

Finding Neabsco Creek too high to ford after the week's rains, the battalion returned to Occoquan for the night, whether waiting for the Occoquan River to go down in height or planning to spend another day searching for booty not specified in the report.

The next morning the fords were still impassable, and hearing from good authority that a force of rebel cavalry were in the vicinity, I resolved to cross the Occoquan, which I did by swimming the horses and carrying the men in small boats.Major Jones claimed the men of Occoquan were mostly Unionist, but at least one wasn't. "I arrested and kept in confinement Basil Brawner, a justice of the peace," he reported, "but released him on parole of honor when I left." Probably it was just too hard to get Brawner in the boats before the phantom Confederate horsemen (Brawner, later a state legislator, was killed in a horrific traffic accident in Alexandria at the age of 90).

The battalion of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry rode back into camp the morning of March 21, without ever having made contact with the enemy and therefore with nothing but caches of Confederate equipment to report. Meanwhile, on Alexandria's finger ridge, Fitz John Porter was preparing to embark his First Division, Third Corps on ships on the Potomac the following morning for transport to the Peninsula.

For some stellar accounts of preparation for the Peninsula Campaign with great local flavor covering "Baldy" Smith's First Division, Fourth Corps and George McCall's Pennsylvania Reserves check out All Not So Quiet Along the Potomac.

Great blog.

ReplyDeleteOne of my clients is publishing a book next month on the Great Debate of 1850. How can I get it out to you to consider for a possible review?

Neil

Neil, if you want to leave me a link to the book in the comments I'm happy to take a look at the previews and see if I can work something in.

DeleteGreat account, once again, and thanks for the compliment. If readers look at your posts and mine, they will gain quite an understanding of the Army of the Potomac around DC in March 1862. I really enjoy exploring this more obscure history that is so overshadowed by the Peninsula Campaign on the one end, and First Bull Run on the other!

ReplyDeleteThanks, Ron. I find myself more and more excited about the troops leaving for the Peninsula, so that there will be more space to look at these obscure corners. And, of course, the rise of Mosby....

Delete