|

| Winfield Scott and the Lincoln Cabinet |

Several days earlier, Scott had asked McDowell to make a plan for attacking Confederate forces defending Manassas Junction led by G.T. Beauregard. The younger man had been chosen based on his excellent career as a staffer and had duly sketched out an intricate plan, involving moving his army of 30,000 (the largest army the Federal government had under its command) from its camps in Alexandria County (Arlington) to Centreville, where he would cross Bull Run at an undefended place, and attack Beauregard's defenses from the back.

In modern military terms, McDowell had created an operational-level plan (and a pretty sound one). It dictated the movement of an army to a battlefield, where tactical-level decisions could be made (the decisions regarding movement of units on a battlefield). Scott saw McDowell's operations as a part of his strategic-level plan. A plan to defeat the South "with less bloodshed than any other plan."

Scott had been refining this strategy for over a month, since he first put it to writing in response to rising star George McClellan. McClellan had written Scott at the end of April, proposing an operational-level plan that he had confused with a strategy, wherein soldiers under his command in the Department of the Ohio would march down Virginia's Kanawha River, then turn east and turn east to take Richmond.

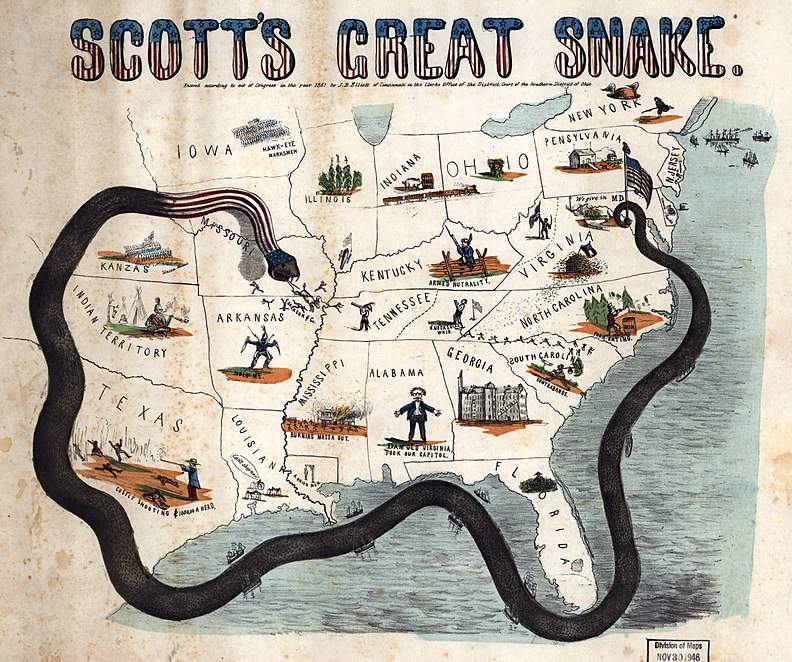

Scott had patiently responded with the flaws in McClellan's operation (mainly, the militia regiments would barely begin marching before their ninety-days ran out and the three-years volunteers would need much longer to train), but also included his own strategic recommendation. Believing a strategy based on operational conquest would succeed in creating "no more than fifteen devastated provinces not to be brought into harmony with their conquerors, but to be held for generations, by heavy garrisons, at an expense quadruple the net duties or taxes which it would be possible to extort from them," Scott proposed instead surrounding the rebel states until moderates and Unionists overthrew their secessionist leaders.

The plan relied on using the Mississippi River and its largest tributaries to move and supply a large force, which would take complete control of the river, while the U.S. Navy blockaded Southern ports. In so doing, he could minimize bloodshed, and thus minimize propaganda about bloodthirsty Northerners. He had left McClellan with "a word now about our greatest obstacle in the way of this plan - the great danger now pressing upon us - the impatience of our patriotic and loyal Union friends. They will urge instant and vigorous action, regardless, I fear, of consequences."

|

| J.B. Elliott cartoon mocking Scott's plan |

Scott was probably not surprised, then, when the President himself supported an immediate move on Manassas Junction. The general-in-chief patiently explained again that the ninety-day militia was not reliable and that they would be better served by waiting for the three-year volunteers to complete their training before putting McDowell's plan into action, but then things began to go wrong.

The Cabinet was well aware that the ninety-day militia would begin ending their term of service in the last weeks of July and the three-year volunteers were only just beginning to arrive, guaranteeing a gap in military operations. Furthermore, they knew that the Confederate Congress was due to convene on July 20 in Richmond, and any disruption of that event would be helpful in de-legitimizing the rebel government.

The Cabinet began asking McDowell if he could march immediately for Manassas Junction. Ever the staffer, McDowell acknowledged that he could do it, but asked to wait until the three-year men were ready all the same. Scott became frustrated with the Cabinet (and when Scott got frustrated, he always got huffy), and McDowell was stuck between an angry superior officer and angry civilian leadership. Brigadier General Montgomery Meigs, the Quartermaster-General of the Army (he had replaced Joe Johnston when he resigned at Virginia's secession) was asked for his opinion on the matter. As the man who had supervised construction of the Capitol's new wings, Meigs was well-known to the politicians of Washington and had already helped the Lincoln Administration a number of times.

Meigs provided the Cabinet the cover they needed to overrule Scott, by agreeing with McDowell that attacking Manassas could be done, and that it might even mean a quick end to the war. He described his advice later as "it was better to whip them here than to go far into an unhealthy country to fight them [meaning down the Mississippi, where malaria was omnipresent]... To make the fight in Virginia was cheaper and better as the case now stood."

One can easily imagine the good aide McDowell momentarily panicked at having unintentionally aided impulsiveness in winning the day (not to mention the likelihood of angering Scott, notorious for his long-held grudges). Or one can just as easily imagine the unsung staffer McDowell, excited at his chance to play what he expected to be the pivotal role in the secession crisis against the South's most lauded hero. Either way, he tried to improve his chances by delaying the attack. "This is not an army," he told the Cabinet about the men in his department. "It will take a long time to make an army."

"You are green, it is true," Lincoln acknowledged. "But they are green, also. You are all green alike."

Print Sources:

- The Battle Cry of Freedom, by James P. McPherson

- The Longest Night, by David Eicher

I'm reading your posts in Reader, so I don't know if it is counting that in your page view stats. I just wanted you to know that I am following these posts daily, and that they've largely replaced The New York Times blog as a more enjoyable play by play!

ReplyDeleteGlad you're enjoying! After Manassas, I'm hoping to extend beyond the Civil War more, but right now there's a lot of exciting stuff going on in the area.

ReplyDelete