This is the fourth in a four-part series on the impact of the Mexican War on the American Civil War.

On March 29, 1847, after 12 days of siege, Vera Cruz surrendered to Major General Winfield Scott and he could finally begin his campaign in earnest (when Congress made him Brevet Lieutenant General in 1855, they dated it to the capitulation of Vera Cruz). It had been a harder siege than Scott had expected (his landing outside the city was the first large-scale amphibious operation in U.S. history), but it was over and he could have a firm base of operations for a march on the Mexican capital that would force the dictator General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna to sign a peace treaty recognizing the Rio Grande as the border of the two countries and selling Alta California to the United States.

A wave of yellow fever had hit his army during the siege, so Scott reduced his force to the 8,500 healthier men and began marching west towards Mexico City. Santa Anna was waiting for him in a narrow pass near the village of Cerro Gordo with a new army (12,000 strong) since Zachary Taylor had routed his old one a month and a half earlier at Buena Vista. He carefully dug them in and surrounded them with artillery, including the fearsome San Patricio Battalion, but the surprise was ruined because Scott had let the dragoons lead his advance. When they tripped the ambush, Scott fell back and planned.

The solution was provided by an engineer on his staff, Lieutenant Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, who found some trails through the mountains behind Santa Anna's army. Scott decided to send a division of regulars through the pass, splitting it into two parts to attack at two places. He would then split a division of volunteers led by Brigadier General Robert Patterson, using one of its brigades to keep Santa Anna distracted, while the other cut off the retreat.

When the battle kicked off on April 18, Patterson's diversionary brigade bungled the whole operation. Brigadier General Gideon Pillow had a commission because he had been President James K. Polk's law partner, and he decided the path chosen for him was too dangerous, and took a different one instead. The result was that Santa Anna was not kept busy, and the flanking movement was limited in its effectiveness. Still, with the guidance of Beauregard, Patterson's other brigade (led by the 4th Illinois, under command of Colonel Edward Baker) was able to achieve enough surprise to capture Santa Anna's wooden leg, along with around 3,000 Mexicans. The bigger haul, though, was the 40 pieces of artillery abandoned by Santa Anna's men.

Santa Anna returned to Mexico City to fight off another coup, while Scott moved into the city of Puebla to get his army organized. His supplies were under constant attack by guerrillas, some associated with the Mexican government, some rebels, and some just bandits. And it was on June 11, that Brevet Captain Joe Hooker finally got back into the action because of them. He had been named chief-of-staff for a political general, finally escaping from Zachary Taylor's dormant Army of Occupation in northern Mexico. With two companies of regular infantry, Hooker stormed a position held by guerrillas, and opened the road from Vera Cruz to Puebla again for supply wagons (the bandits would not take long to return).

Hooker arrived in July, when Scott was reorganizing his army. Many of the volunteers term-of-service was expiring (including Robert Patterson's) and with additional regular army units, he took the opportunity to get rid of almost all the rest from his mobile force. The capture of Mexico City would be professional, he declared, unlike the pillaging of northern Mexico. Scott split his men into four divisions, with a separate division of dragoons. But Polk's liberal bestowal of commissions had left him with the need to use political generals, and Pillow ended up in command of the Third Division. Scott picked Hooker to be his chief-of-staff to make sure a mistake like at Cerro Gordo didn't reoccur. Scott also counted on the talented staff he had assembled around himself, including engineers Beauregard, Robert E. Lee, and George B. McClellan, as well as ordnance officer Charles P. Stone (one officer bitterly left out was George Meade, since Scott relied on his own engineers on staff, rather than the army's engineers).

Scott's army, now over 10,000 strong, rolled into motion again on August 7. The area around Mexico City alternates between marshland, lakes and mountains, a seemingly nightmarish place to assault, especially since Santa Anna had 25,000 men. But few were trained soldiers outside the revered, but now substantially battered Mexican cavalry. And Santa Anna was critically low on artillery.

The first conflict came on August 19, when Scott's dragoons again came upon a fortified stretch of the road blocking the way to the town of Churubusco, surrounded by a rough lava bed (called a pedregal, in this case close to the site of Mexico City airport today). After sending Lee to investigate, Scott decided to flank around Churubusco through some paths Lee had found, and sent Pillow with his own and another division to accomplish the task, while he and the other two divisions kept Santa Anna pinned down.

But on August 19, Hooker road back to Scott at full speed, to let him know Santa Anna has stationed 6,000 men and 28 guns blocking the pass. "[I] did not send General Pillow out there to fight a battle, but to build a road," Scott told Hooker irritably, giving him orders to be cautious. But when Hooker got back to Pillow, he found the general already planning a frontal attack, and rather than urge caution, helped to quicken the preparations. The frontal attack was led by Brigadier General Franklin Pierce and went very badly. Hooker's help in coordinating the movements did little more than expose more Americans to the murderous Mexican fire. Worse, Santa Anna was clearly preparing to drop a crushing blow on the two isolated U.S. divisions, potentially ending Scott's campaign.

Enraged, Scott summoned Pillow and Hooker while the fighting was still occurring that evening. His holding action at Churubusco was going to have to be turned into a full scale assault to prevent Santa Anna from destroying half the American army. He finally dismissed them after dark, but in the pouring rain they became lost in the pedregal and had to spend the night there. In the morning, Hooker's horse was missing, and Pillow went on alone. He hurried his horse as he heard the sounds of combat and arrived to find his command had won a great victory without him. A brigade commander had decided on his own initiative to lead three brigades around a narrow mountain pass in the midst of the stormy night and attacked from the village of Contreras at dawn, scattering the unprepared Mexicans. Among the heroes were two First Lieutenants in the 6th Infantry that would remain lifelong friends, Lo Armistead and Win Hancock.

Enraged, Scott summoned Pillow and Hooker while the fighting was still occurring that evening. His holding action at Churubusco was going to have to be turned into a full scale assault to prevent Santa Anna from destroying half the American army. He finally dismissed them after dark, but in the pouring rain they became lost in the pedregal and had to spend the night there. In the morning, Hooker's horse was missing, and Pillow went on alone. He hurried his horse as he heard the sounds of combat and arrived to find his command had won a great victory without him. A brigade commander had decided on his own initiative to lead three brigades around a narrow mountain pass in the midst of the stormy night and attacked from the village of Contreras at dawn, scattering the unprepared Mexicans. Among the heroes were two First Lieutenants in the 6th Infantry that would remain lifelong friends, Lo Armistead and Win Hancock.

Hooker arrived in time to see Winfield Scott taking advantage of his sudden reversal of luck. Continuing to press up the main road with one division, he sent a third to follow Pillow's two divisions through the mountain. They linked up at Churubusco and found that the First Division had pushed the Mexican army back onto the grounds of a convent. Two divisions assaulted the convent and were driven off by vicious fire from the Mexicans, and, especially, the San Patricios. But Santa Anna's poor organizational hierarchy began to fail him, and ammunition was delivered to the defenders that did not fit in their weapons. After several attempts to surrender were blocked by the San Patricios, who tore down white flags and shot anyone trying to give up, the Mexicans finally ran out of ammunition and the Americans surrounded the convent at point blank range. Hooker was sent in to receive the surrender, and over the next few hours, Santa Anna lost almost half his army, as 10,000 Mexicans were either captured, killed, or just plain ran away. Over half of the San Patricios were captured or killed.

Scott followed his victory with an armistice, as Taylor had done after Monterrey. He and President Polk's diplomatic envoy began to argue a treaty with the Mexicans, but Santa Anna was probably just buying time to defeat internal opponents (and probably didn't even have authority to negotiate). He and Scott exchanged prisoners, he escorted some of Scott's men through Mexico City to purchase food for the army, and he offered a boundary of the Rio Grande, but he refused to discuss Alta California and demanded the release of the San Patricios. Both were non-starters with Scott. Polk wanted Alta California and Scott wanted the San Patricios to pay. Eventually, nearly fifty of them would be hung, the rest severely whipped and branded with a "D" for deserter on their cheeks.

By September 6, the cease-fire was over and Scott was back on the move. His first target was a factory at El Molino del Rey, which spies told him was being used to melt down church bells and make cannon (a ridiculous claim, it turned out). Scott sent his First Division, with one of Pillow's brigades in case of unanticipated trouble, but Pillow and Hooker were left out of the battle. In the poorly executed battle of September 8, the 2,800 Americans suffered 800 casualties (mostly wounded) while driving away 4,000 Mexicans (who suffered about 1,600 casualties themselves). The handy work of artillery under Captain Robert Anderson was one of the loan bright spots in an otherwise bungled battle. (Today, the site of the Molino del Rey is the Executive Mansion for the President of Mexico, known as Los Pinos).

On the same day, Scott had sent his engineers out to try to find a way into Mexico City. The most formidable obstacle was a massive hill with a fortress on top called Chapultepec Castle, close to where Molino del Rey was being fought (the fortress was home to Mexico's military academy). On September 11, Scott assembled his generals to hear the report of his staff and choose an option. Lee and most of the staff favored an approach from the south, bypassing Chapultepec. But Beauregard was dragged into the conference by two generals that had been speaking to him earlier, arguing for an attack on the fortress itself as the quicker move, before Santa Anna could complete defenses. It swayed a slim majority of the council of war and Scott went along with the choice.

All day on September 12, American artillery bombarded Chapultepec (a battery under Captain John Magruder was particularly impressive, including Lt. Thomas Jackson). On September 13, Pillow's division was to back up the First and Fourth Divisions, but Hooker arranged to join one of the hand-picked storming parties, who would run up in front of the army and place the ladders to climb over the walls of the fortress. Hooker was leading a group of light infantry commanded by Joe Johnston when they reached their designated point. But the ladders were not there yet, and Hooker reluctantly left to find them.

While he ordered them to move faster, he came up with an idea to flank the fortress by another route. He found Gideon Pillow, miserably sitting on the ground with blood gushing from a wound in his foot, and breathlessly explained his plan. Pillow gave permission (Hooker says because it was so brilliant, but one can easily imagine the general just wanting him to go away) and Hooker took the 6th Infantry, but quickly found out that his discovered path was a bust. But he had a great view of Johnston's light infantry going over the wall without him (though they were not first, that honor belonged to George Pickett after James Longstreet was shot). Except for six cadets that fought to the death, the Mexican army disintegrated.

By September 14, the United States Marines were in control (barely) of Mexico City, the fabled Halls of Montezuma.

The war was over, but the fighting would drag on and on, as guerrillas and peasant revolts merged together. Santa Anna was forced to cede power, but lead a campaign against Scott's supply bases at Vera Cruz. He would be forced back into exile in 1851, but would be back in 1853 to sell the United States some more land in the Gadsen Purchase. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo would be signed to formally cede the present-day American Southwest to the United States in 1848. Polk would declare himself a successful president, having accomplished all of his campaign pledges, but it wouldn't keep his party in the White House. His would-be-successor, Lewis Cass, lost out to the Whig candidate, Zachary Taylor.

But Taylor had been nominated by a Whig Party without direction. Unable to argue against the success of the Mexican War, they had instead picked its greatest hero, while arguing its immorality. Taylor then made things worse by dying 16 months into his presidency, and elevating his Southern Whig Vice President, Millard Fillmore, to the White House. Fillmore's pro-slavery views (he signed the explosive Fugitive Slave Act into law) exacerbated the rift in the Whigs, and in 1852 the Northern Whigs triumphed by denying him the nomination, giving it instead to an anti-slavery Whig, none other than Winfield Scott, but at the price of a Southern Whig platform that supported the Fugitive Slave Act and extending slavery into the new Mexican War territory. The compromise excited no one, and Scott lost to his former subordinate, Franklin Pierce, an indignity that irked him so much he moved the general-in-chief headquarters to New York City, not to return until Spring 1861. The result for the Whigs was worse: they fractured into the Free Soil Party, the Know Nothing Party, Northern Whigs, and Southern Whigs. In 1856, John C. Fremont would reunite all but the last as the Republican Party.

For Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Joe Hooker, like many younger officers, the end of the war marked a drastic decline in his fortunes. The opportunity and excitement that war had provided was suddenly gone. While some officers could readjust to the old pace of fighting Indians and maintaining procedures, Hooker was one who could not. While still pacifying the Mexican countryside, Gideon Pillow had leaked a number of his very one-sided or even outright falsified reports to reporter friends and the New Orleans papers had published them. The overall theme was that at Contrerras and Cerro Gordo, Scott had been incompetent and given Pillow impossible tasks that only his ingenuity had saved from disaster. He was backed up by the commander of Scott's First Division, which gave him a bit more credibility.

Scott had both arrested, but was overruled by Polk. Scott then convened a court martial for Pillow, and Hooker testified the Pillow was a good general on four separate occasions, supporting his arguments that he had made sound decisions, even if he didn't outright criticize Scott. In the end, Polk recalled Scott from Mexico and one of Pillow's staffers took credit for leaking the reports to get the general off the hook. Scott never forgave Hooker, or any of the officers who testified for Pillow, especially not after Pillow helped damage Scott's military record on behalf of Franklin Pierce in the 1852 election.

Hooker wound up in California, where he befriended Phil Kearny and George Stoneman, two men who would have a heavy influence on his Civil War career. He left the army, tried to start a farm in the Napa Valley, but found the excitement of gambling, drinking, and womanizing far more appealing. Hooker ran up huge debts, but made friends that helped him stave off complete ruin and when G.T. Beauregard fired on Robert Anderson at Fort Sumter, longed for the chance to be back in battle.

So he wrote Senator Edward Baker, met Abraham Lincoln, and hung around Washington making friends with the Massachusetts Congressional delegation, but Winfield Scott put the kibosh on his attempt to receive a commission. The spark of the Civil War lies in the result of the Mexican War. The violent sectional tearing that war caused reached its culmination in 1861 and the nation could not escape from its long shadow anymore than Hooker could escape from the wrath of the "Old Man of the Army".

Print Sources:

|

| Scott's entry into Mexico City, as painted by Austrian Carl Nebel in 1851 |

On March 29, 1847, after 12 days of siege, Vera Cruz surrendered to Major General Winfield Scott and he could finally begin his campaign in earnest (when Congress made him Brevet Lieutenant General in 1855, they dated it to the capitulation of Vera Cruz). It had been a harder siege than Scott had expected (his landing outside the city was the first large-scale amphibious operation in U.S. history), but it was over and he could have a firm base of operations for a march on the Mexican capital that would force the dictator General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna to sign a peace treaty recognizing the Rio Grande as the border of the two countries and selling Alta California to the United States.

A wave of yellow fever had hit his army during the siege, so Scott reduced his force to the 8,500 healthier men and began marching west towards Mexico City. Santa Anna was waiting for him in a narrow pass near the village of Cerro Gordo with a new army (12,000 strong) since Zachary Taylor had routed his old one a month and a half earlier at Buena Vista. He carefully dug them in and surrounded them with artillery, including the fearsome San Patricio Battalion, but the surprise was ruined because Scott had let the dragoons lead his advance. When they tripped the ambush, Scott fell back and planned.

The solution was provided by an engineer on his staff, Lieutenant Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, who found some trails through the mountains behind Santa Anna's army. Scott decided to send a division of regulars through the pass, splitting it into two parts to attack at two places. He would then split a division of volunteers led by Brigadier General Robert Patterson, using one of its brigades to keep Santa Anna distracted, while the other cut off the retreat.

When the battle kicked off on April 18, Patterson's diversionary brigade bungled the whole operation. Brigadier General Gideon Pillow had a commission because he had been President James K. Polk's law partner, and he decided the path chosen for him was too dangerous, and took a different one instead. The result was that Santa Anna was not kept busy, and the flanking movement was limited in its effectiveness. Still, with the guidance of Beauregard, Patterson's other brigade (led by the 4th Illinois, under command of Colonel Edward Baker) was able to achieve enough surprise to capture Santa Anna's wooden leg, along with around 3,000 Mexicans. The bigger haul, though, was the 40 pieces of artillery abandoned by Santa Anna's men.

Santa Anna returned to Mexico City to fight off another coup, while Scott moved into the city of Puebla to get his army organized. His supplies were under constant attack by guerrillas, some associated with the Mexican government, some rebels, and some just bandits. And it was on June 11, that Brevet Captain Joe Hooker finally got back into the action because of them. He had been named chief-of-staff for a political general, finally escaping from Zachary Taylor's dormant Army of Occupation in northern Mexico. With two companies of regular infantry, Hooker stormed a position held by guerrillas, and opened the road from Vera Cruz to Puebla again for supply wagons (the bandits would not take long to return).

Hooker arrived in July, when Scott was reorganizing his army. Many of the volunteers term-of-service was expiring (including Robert Patterson's) and with additional regular army units, he took the opportunity to get rid of almost all the rest from his mobile force. The capture of Mexico City would be professional, he declared, unlike the pillaging of northern Mexico. Scott split his men into four divisions, with a separate division of dragoons. But Polk's liberal bestowal of commissions had left him with the need to use political generals, and Pillow ended up in command of the Third Division. Scott picked Hooker to be his chief-of-staff to make sure a mistake like at Cerro Gordo didn't reoccur. Scott also counted on the talented staff he had assembled around himself, including engineers Beauregard, Robert E. Lee, and George B. McClellan, as well as ordnance officer Charles P. Stone (one officer bitterly left out was George Meade, since Scott relied on his own engineers on staff, rather than the army's engineers).

Scott's army, now over 10,000 strong, rolled into motion again on August 7. The area around Mexico City alternates between marshland, lakes and mountains, a seemingly nightmarish place to assault, especially since Santa Anna had 25,000 men. But few were trained soldiers outside the revered, but now substantially battered Mexican cavalry. And Santa Anna was critically low on artillery.

The first conflict came on August 19, when Scott's dragoons again came upon a fortified stretch of the road blocking the way to the town of Churubusco, surrounded by a rough lava bed (called a pedregal, in this case close to the site of Mexico City airport today). After sending Lee to investigate, Scott decided to flank around Churubusco through some paths Lee had found, and sent Pillow with his own and another division to accomplish the task, while he and the other two divisions kept Santa Anna pinned down.

But on August 19, Hooker road back to Scott at full speed, to let him know Santa Anna has stationed 6,000 men and 28 guns blocking the pass. "[I] did not send General Pillow out there to fight a battle, but to build a road," Scott told Hooker irritably, giving him orders to be cautious. But when Hooker got back to Pillow, he found the general already planning a frontal attack, and rather than urge caution, helped to quicken the preparations. The frontal attack was led by Brigadier General Franklin Pierce and went very badly. Hooker's help in coordinating the movements did little more than expose more Americans to the murderous Mexican fire. Worse, Santa Anna was clearly preparing to drop a crushing blow on the two isolated U.S. divisions, potentially ending Scott's campaign.

Enraged, Scott summoned Pillow and Hooker while the fighting was still occurring that evening. His holding action at Churubusco was going to have to be turned into a full scale assault to prevent Santa Anna from destroying half the American army. He finally dismissed them after dark, but in the pouring rain they became lost in the pedregal and had to spend the night there. In the morning, Hooker's horse was missing, and Pillow went on alone. He hurried his horse as he heard the sounds of combat and arrived to find his command had won a great victory without him. A brigade commander had decided on his own initiative to lead three brigades around a narrow mountain pass in the midst of the stormy night and attacked from the village of Contreras at dawn, scattering the unprepared Mexicans. Among the heroes were two First Lieutenants in the 6th Infantry that would remain lifelong friends, Lo Armistead and Win Hancock.

Enraged, Scott summoned Pillow and Hooker while the fighting was still occurring that evening. His holding action at Churubusco was going to have to be turned into a full scale assault to prevent Santa Anna from destroying half the American army. He finally dismissed them after dark, but in the pouring rain they became lost in the pedregal and had to spend the night there. In the morning, Hooker's horse was missing, and Pillow went on alone. He hurried his horse as he heard the sounds of combat and arrived to find his command had won a great victory without him. A brigade commander had decided on his own initiative to lead three brigades around a narrow mountain pass in the midst of the stormy night and attacked from the village of Contreras at dawn, scattering the unprepared Mexicans. Among the heroes were two First Lieutenants in the 6th Infantry that would remain lifelong friends, Lo Armistead and Win Hancock.Hooker arrived in time to see Winfield Scott taking advantage of his sudden reversal of luck. Continuing to press up the main road with one division, he sent a third to follow Pillow's two divisions through the mountain. They linked up at Churubusco and found that the First Division had pushed the Mexican army back onto the grounds of a convent. Two divisions assaulted the convent and were driven off by vicious fire from the Mexicans, and, especially, the San Patricios. But Santa Anna's poor organizational hierarchy began to fail him, and ammunition was delivered to the defenders that did not fit in their weapons. After several attempts to surrender were blocked by the San Patricios, who tore down white flags and shot anyone trying to give up, the Mexicans finally ran out of ammunition and the Americans surrounded the convent at point blank range. Hooker was sent in to receive the surrender, and over the next few hours, Santa Anna lost almost half his army, as 10,000 Mexicans were either captured, killed, or just plain ran away. Over half of the San Patricios were captured or killed.

Scott followed his victory with an armistice, as Taylor had done after Monterrey. He and President Polk's diplomatic envoy began to argue a treaty with the Mexicans, but Santa Anna was probably just buying time to defeat internal opponents (and probably didn't even have authority to negotiate). He and Scott exchanged prisoners, he escorted some of Scott's men through Mexico City to purchase food for the army, and he offered a boundary of the Rio Grande, but he refused to discuss Alta California and demanded the release of the San Patricios. Both were non-starters with Scott. Polk wanted Alta California and Scott wanted the San Patricios to pay. Eventually, nearly fifty of them would be hung, the rest severely whipped and branded with a "D" for deserter on their cheeks.

By September 6, the cease-fire was over and Scott was back on the move. His first target was a factory at El Molino del Rey, which spies told him was being used to melt down church bells and make cannon (a ridiculous claim, it turned out). Scott sent his First Division, with one of Pillow's brigades in case of unanticipated trouble, but Pillow and Hooker were left out of the battle. In the poorly executed battle of September 8, the 2,800 Americans suffered 800 casualties (mostly wounded) while driving away 4,000 Mexicans (who suffered about 1,600 casualties themselves). The handy work of artillery under Captain Robert Anderson was one of the loan bright spots in an otherwise bungled battle. (Today, the site of the Molino del Rey is the Executive Mansion for the President of Mexico, known as Los Pinos).

On the same day, Scott had sent his engineers out to try to find a way into Mexico City. The most formidable obstacle was a massive hill with a fortress on top called Chapultepec Castle, close to where Molino del Rey was being fought (the fortress was home to Mexico's military academy). On September 11, Scott assembled his generals to hear the report of his staff and choose an option. Lee and most of the staff favored an approach from the south, bypassing Chapultepec. But Beauregard was dragged into the conference by two generals that had been speaking to him earlier, arguing for an attack on the fortress itself as the quicker move, before Santa Anna could complete defenses. It swayed a slim majority of the council of war and Scott went along with the choice.

All day on September 12, American artillery bombarded Chapultepec (a battery under Captain John Magruder was particularly impressive, including Lt. Thomas Jackson). On September 13, Pillow's division was to back up the First and Fourth Divisions, but Hooker arranged to join one of the hand-picked storming parties, who would run up in front of the army and place the ladders to climb over the walls of the fortress. Hooker was leading a group of light infantry commanded by Joe Johnston when they reached their designated point. But the ladders were not there yet, and Hooker reluctantly left to find them.

While he ordered them to move faster, he came up with an idea to flank the fortress by another route. He found Gideon Pillow, miserably sitting on the ground with blood gushing from a wound in his foot, and breathlessly explained his plan. Pillow gave permission (Hooker says because it was so brilliant, but one can easily imagine the general just wanting him to go away) and Hooker took the 6th Infantry, but quickly found out that his discovered path was a bust. But he had a great view of Johnston's light infantry going over the wall without him (though they were not first, that honor belonged to George Pickett after James Longstreet was shot). Except for six cadets that fought to the death, the Mexican army disintegrated.

By September 14, the United States Marines were in control (barely) of Mexico City, the fabled Halls of Montezuma.

The war was over, but the fighting would drag on and on, as guerrillas and peasant revolts merged together. Santa Anna was forced to cede power, but lead a campaign against Scott's supply bases at Vera Cruz. He would be forced back into exile in 1851, but would be back in 1853 to sell the United States some more land in the Gadsen Purchase. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo would be signed to formally cede the present-day American Southwest to the United States in 1848. Polk would declare himself a successful president, having accomplished all of his campaign pledges, but it wouldn't keep his party in the White House. His would-be-successor, Lewis Cass, lost out to the Whig candidate, Zachary Taylor.

|

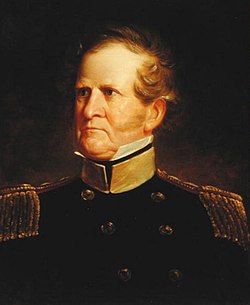

| Winfield Scott, shortly after the Mexican War |

For Brevet Lieutenant Colonel Joe Hooker, like many younger officers, the end of the war marked a drastic decline in his fortunes. The opportunity and excitement that war had provided was suddenly gone. While some officers could readjust to the old pace of fighting Indians and maintaining procedures, Hooker was one who could not. While still pacifying the Mexican countryside, Gideon Pillow had leaked a number of his very one-sided or even outright falsified reports to reporter friends and the New Orleans papers had published them. The overall theme was that at Contrerras and Cerro Gordo, Scott had been incompetent and given Pillow impossible tasks that only his ingenuity had saved from disaster. He was backed up by the commander of Scott's First Division, which gave him a bit more credibility.

Scott had both arrested, but was overruled by Polk. Scott then convened a court martial for Pillow, and Hooker testified the Pillow was a good general on four separate occasions, supporting his arguments that he had made sound decisions, even if he didn't outright criticize Scott. In the end, Polk recalled Scott from Mexico and one of Pillow's staffers took credit for leaking the reports to get the general off the hook. Scott never forgave Hooker, or any of the officers who testified for Pillow, especially not after Pillow helped damage Scott's military record on behalf of Franklin Pierce in the 1852 election.

Hooker wound up in California, where he befriended Phil Kearny and George Stoneman, two men who would have a heavy influence on his Civil War career. He left the army, tried to start a farm in the Napa Valley, but found the excitement of gambling, drinking, and womanizing far more appealing. Hooker ran up huge debts, but made friends that helped him stave off complete ruin and when G.T. Beauregard fired on Robert Anderson at Fort Sumter, longed for the chance to be back in battle.

So he wrote Senator Edward Baker, met Abraham Lincoln, and hung around Washington making friends with the Massachusetts Congressional delegation, but Winfield Scott put the kibosh on his attempt to receive a commission. The spark of the Civil War lies in the result of the Mexican War. The violent sectional tearing that war caused reached its culmination in 1861 and the nation could not escape from its long shadow anymore than Hooker could escape from the wrath of the "Old Man of the Army".

Print Sources:

- Eagles and Empire: The United States, Mexico, and the Struggle for a Continent by David A. Cleary

- Fighting Joe Hooker by Walter H. Herbert

- The Battle Cry of Freedom by James McPherson

No comments:

Post a Comment