|

| Lincoln's note to Mansfield |

The inclosed papers of Colonel Joseph Hooker speak for themselves. He desires to have command of a regiment. Ought he have it, and can it be done, and how?

Please consult General Scott, and say if he and you would like Colonel Hooker to have a command.

The note was addressed to Brigadier General Joseph Mansfield, in command of the Department of Washington, the District of Columbia, and Maryland from Bladensburg to Fort Washington. At the outbreak of the outbreak of the war, Mansfield had been the Inspector General for the U.S. Army, but the need for experienced leaders (he had fought in Mexico with future president - and Winfield Scott arch-rival - Zachary Taylor). Mansfield was charged with protecting 1861 Washington, D.C., which consisted of Washington City (today's Mall, the Capitol, and the White House, there wasn't much else there) and Georgetown, plus a few small villages, like Silver Spring. (Mansfield would be killed at the Battle of Antietam and would have a fort defending Friendship Heights named in his honor -- though the fort named after his cousin who died of illness in 1864, Joseph Totten, would have a more lasting mark on the city).

Of course, Mansfield felt chronically short of men and materiel, since the first priority was fully manning the Department of Northeast Virginia, based in Alexandria and encompassing all the land south of the Potomac, east of the Allegheny mountains, and north of the James River. It was headed by Brigadier General Irvin McDowell, another officer he had been working on administrative duties in Washington at the beginning of the war. Mansfield was senior, having joined the army in 1822 (their promotions to brigadier general were both dated May 14, 1861, though McDowell had only been a major before while Mansfield had been a colonel).

|

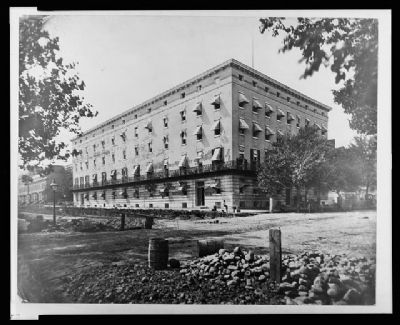

| The Winder Building, after the Civil War |

Scott's offices were located in the Winder Building, across the street from the War Department, still standing on the corner of 17th and F, NW, and currently used by the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. Scott had moved to New York City from his offices in Washington after losing the Presidential election to Franklin Pierce and only returned after South Carolina seceded. Meanwhile, the building had remained the Bureau of the Adjutant General.

War history is romantically told in terms of the generals on battlefields or strategists in late-night debates or, occasionally, the everyday individuals who do the fighting and dying. But rarely is it ever told in terms of the immense amount of staff work that goes into every decision. The Adjutant General Bureau was the 1861 U.S. Army staff, charged with maintaining military communications, coordinating the various functions of the army like the quartermaster and the medical corps, and translating the ideas of the generals commanding into specific orders. McDowell, Mansfield, and Hooker had all, at one time, served in this capacity.

The Adjutant General (adjutant comes from the Latin adjuvare, to help, from which also comes "aid") was Lorenzo Thomas and he had a staff of thirteen officers to help him out. One of these, Assistant Adjutant General Edward Townsend (his grade was lieutenant colonel, but he was usually referred to by his AAG title), Scott had tapped to also be his chief of staff, and Hooker's credentials, with whatever commentary Mansfield may have attached, would have been dropped on his desk.

June 19 was a busy day for Townsend, as he gathered information about the Northern armies operations and made sure Scott had a firm understanding of the strategic situation. On his desk was a message from Charles P. Stone (it was Townsend, and not Scott, to whom Stone addressed his daily reports, and who would have forwarded his request for more artillery ammunition to the quartermaster), defending the crossings of the Potomac, with intelligence on the Confederate Army that had recently been at Harper's Ferry. He was also dealing with suggestions from Scott's up and coming competition, George McClellan, about areas outside of his command ("You had better reinforce [Robert] Patterson immediately." Scott's late-night reply: "I do not credit the existence of any formidable rebel force in the mountains... and have said so to Patterson.") Townsend was also receiving a one-sided conversation from Patterson himself, wherein the veteran general convinced himself first to and then not to advance to Maryland Heights so he could seize Harper's Ferry at long last. Finally, he was delivered a nasty note from Benjamin Butler, a general at Fort Monroe on Hampton Roads about a delay in the delivery of transport ships.

And none of that took into account his work on putting the finishing touches on Scott's plan for Grand Strategy to win the war to present to the President and the Cabinet, or his need to manage the recent crisis at Vienna, only just beginning to come into focus. Hooker's credentials were going to have to wait.

No comments:

Post a Comment