|

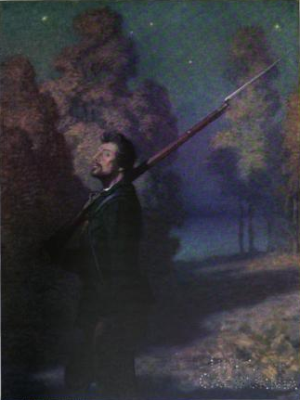

| "The Picket-Guard" by N.C. Wyeth. Illustrating a poem by the same name originally published in Harper's Weekly November 1861. |

Since dunking one of their officers in the Potomac River with a timely cannon shot, Stone's men had developed an understanding of sorts with the men of Eppa Hunton's 8th Virginia - after all, a lot of Stone's men were from Washington and the Virginians were their neighbors.

In fact, on June 22 an event that sounds remarkable, but was actually fairly common, occurred. Stone reliably told Scott: "the opposing pickets at Conrad's Ferry met in the middle of the river, shook hands, and drank to each others health." Stone wasn't trying to warm the general-in-chief's heart, it was possibly important intelligence. "The Virginia picket men said they did not wish to fight, but 'wanted to go home'." (Of course, the moral of Stone's DC militia wasn't much better. He had reported for several days that they ought to be sent home to be replaced.)

Pickets were the eyes and ears of a Civil War-era military unit. One company out of the regiment would be chosen each day and night to act as a trip-wire. Unlike scouts, who would ride out to look for the enemy, pickets simply went a ways in front of the main position and spread out. They waited there, keeping their eyes and ears open. If an enemy was coming to attack, the pickets were supposed to stay under fire long enough to get a good idea what sort of enemy and how many were on their way, and then run back to the regiment and report in.

Like baseball (a game that would become popular with the Union army during their downtime - which is why most early baseball teams showed up in Northern states) pickets had a set of unwritten rules. And the South Carolinians were violating the most important one. Stone reported on June 27 that they had "recommenced the unsoldierly practice of firing at pickets across the river." Pickets felt that their job outside of camp was bad enough, nobody needed to make it any more difficult by shooting at each other. When their time came, they wanted it to be in a real battle. And, also like baseball, a violation of the unwritten rules had a specific retaliation. "The fire was carefully returned and nothing of the kind has taken place for twenty-four hours past."

While the pickets were defining the limit of control on both sides of the Potomac, Stone was still trying to figure out how to be of use with his tiny force across the Potomac from Leesburg. On June 27, Stone received a copy of a letter to Robert Patterson. It was orders from the U.S. Army's general-in-chief Winfield Scott to consider detaching part of his force to join Stone in an operation against Leesburg.

Undoubtedly, the order pleased Stone, but not as much as actually hearing from Patterson would have. Two days earlier, Stone had ridden out to Harper's Ferry personally with several of his staff to investigate the situation there. They had run into Captain John Newton, Patterson's chief engineer, who was also scouting the area. Stone had asked Newton to pass on exhortations for a joint operation or at the very least to secure Harper's Ferry and let Stone focus only on Leesburg. He had written it all up in his daily report to Scott, who had added his own exhortations to Patterson immediately. It was this order that was copied to Stone as an FYI on June 27.

But no word had come from Patterson, either from Newton's message or Scott's order. And Stone knew that waiting was not a neutral activity. The weather had been dry over the month of June ("[the fords were] always numerous, and becoming more so as the dry weather continues"), which meant that Stone would need even more pickets to act as tripwires to be ready in case of an attack.

No comments:

Post a Comment