|

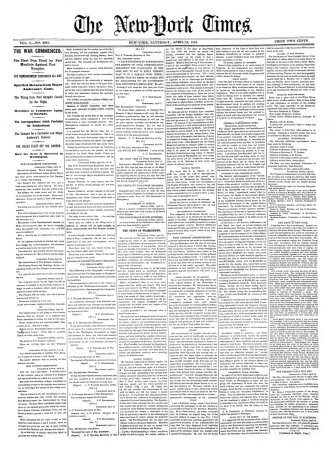

| The New York Times reporting Fort Sumter's attack |

Raymond also wasn't above a little melodrama to attract readers, much like today's New York Post. And his paper's most recent obsession was with G.T. Beauregard. "All who are of any importance of prominence have kept out of the way," the June 2 editorial penned by Raymond continued about the missing Confederate leaders. "Beauregard vanished immediately after the last shot had been fired into the burning Sumter."

It concludes by referencing two items reported elsewhere in the paper by "reliable gentlemen":

The difficulty is at last removed, by the presence of Pseudo-President Davis at Richmond; and of Beauregard at Memphis. The whole case is before us. We shall have forthwith a comparison of the military skill which the veteran [Winfield] Scott and the unpracticed. Davis bring to the field; with a result all themore conclusive, because the best military leader of the South is at the head of the insurgents, and if he be beaten, we have overcome the best material they can throw into the conflict. We may now confidently look for a determination of the question, whether the Southern Congress shall meet at Richmond, or the National Congress at Washington, next month. It is very sure both meetings will not be held.The Times was on the case every day for the next five days, reporting Beauregard's presence in Memphis, Corinth, Richmond, Norfolk, and New Orleans. On June 7 under the headline "Turned Up Again" it responded to a (accurate) report in The Washington Star that Beauregard was at Manassas Junction:

-- The Washington Star of the 5th says: "We have information from two gentlemen of character, whose sympathies with the cause of the Union we know to be entirely reliable, one of whom is just from Manassas Junction, and the other in the immediate vicinity of Leesburgh. The former assures us that on Monday last Gen. Beauregard arrived certainly at the Junction." Gen. Beauregard is surely a myth, appearing and disappearing, dancing about like a veritable Will-of-the-Wisp. Yesterday he was at Memphis, the day before at Montgomery, last week at Charleston, and at various intervening times at Richmond. Now he is at Manassas Gap, and to-morrow he may be -- the Lord knows where. The mystery about the matter is that he seems to have no possible object, accomplishes nothing by being anywhere. He comes and goes without any apparent purpose. Troops neither advance nor retreat, and no demonstrations accompany his movements. He seems to be a spirit, rapping about wherever a circle may be formed to receive his manipulations, without, however, having anything to communicate beyond the manifestation of his presence. This is a very harmless amusement, so long as nobody is hurt, and nobody cares whether he comes or goes. If he follows our advice, however, he will leave Manassas Gap by the first train. The loyal Volunteers are on their way to that post, and Gen. Beauregard is a gentleman with whom they will be very earnest to become acquainted.The next day, he was back in Norfolk according to the Times special correspondent, accompanied by some minor details that would end up proving far more important to the history of warfare:

At Norfolk the steamer Merrimac is raised, and is in the dry-dock and undergoing repairs. The Pennsylvania, and another steamer saved by the enemy, since the sinking at the Navy-yard, are also raised, and are being put into condition to serve as barracks and batteries, hereafter. The number of troops st Richmond he estimates at over 20,000. Gen. Beauregard accompanied my informant from Richmond to Norfolk. The General talks most confidently of prospective success.June 9, it was a report from Charleston reflecting poorly either on its ladies or the Confederate armory (note the dateline, indicating when the report was filed -- newspapers still publish them, even though the news is all now from the date of publication):

HEAD-QUARTERS PROV. ARMY, CONFEDERATE ARMY, CHARLESTON, S.C., Saturday, May 25, 1861. The ladies recently gave a Military Fair in NewOrleans for the benefit of the volunteers, and they could think of no better way of spending the money which they raised than in purchasing a sword for Gen. Beauregard; from which we may infer that this ubiquitous individual was sadly in want of this implement, or that the ladies lacked common sense.To be safe, since Beauregard certainly would have had time to move since late May, Raymond decided to publish a report from a Kentucky paper the same day:

The Louisville Journal says: "A gentleman from Memphis informs us that Gen. Beauregard arrived there a few days since, and used great endeavors to keep his movements secret. Being a stranger, and somewhat observant, he attracted the attention of the Vigilance Committee, who arrested him as a spy and suspected person. The generalissimo of the Confederate forces had to send for Gen. Pillow to identify him, and the hero of Camargo soon convinced the Vigilantes that they had dug their ditch on the wrong side of the rampant of Memphian defence, whereupon Beauregard was discharged with apologies."But on June 10, it was back to Charleston, on the testimony of another special correspondent:

Sunday, June 9. I have learned from a gentleman, whose reliability is beyond a question, that, on Wednesday last, Gen. Beauregard was at Charleston, S.C. There he was seen and conversed, with by my informant, who, though a resident of that city, and a Union man at heart, is compelled by force of public opinion to lend countenance and material aid to the rebel movement. Gen. Beauregard was well, in line spirits and confident of the result of this trouble being victory for the Confederacy. "It is folly," said he, "for us to scatter our forces -- part here, part at Richmond, part at Pensacola and elsewhere. We should, and I am determined to, concentrate a grand army of 60,000 men at some proper point, and compel the United States to attack us.

Beauregard, of course, had taken a rather straight-line trip from Charleston to Richmond to Manassas Junction, arriving there on June 5. And however incorrect the June 10 report from Charleston was, it captured the spirit of Beauregard very well. On June 12, he sat down to write Jefferson Davis a remarkable letter.

No comments:

Post a Comment