|

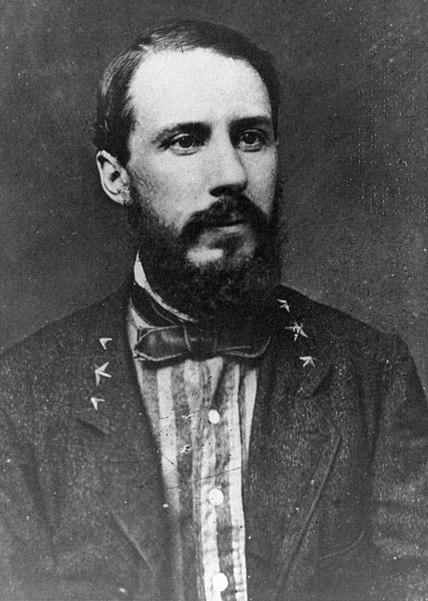

| Porter Alexander as a Confederate colonel |

Alexander's memoir was supposed to have remained a family account, specifically for his beloved daughter, but out of it grew another book, Military Memoirs, published in 1907 as a treatment of the same topic from a military perspective. Unlike the high romance (or schmaltz) of other accounts of the South's most famous army Alexander's contemporaries were writing, he turned a cold, professional eye on its operations, offering praise where earned, and criticism where deserved, even for the already sainted Robert E. Lee. The result was a classic for serious military students, who came to regard Alexander as one of the foremost authorities on the operations of the Confederate army.

But in 1986, another Porter Alexander came to light when his family memoir was published as Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander - a wittier, more thoughtful, and more critical Alexander, and since it's publication it has far eclipsed his more formal book for good reason. It is by far, the most readable memoir by a Civil War soldier.

Alexander was considerably younger than many of the men who would become his colleagues during the war, born in 1835 he was only three when G.T. Beauregard graduated from West Point. He grew up in Georgia and attended West Point, graduating third in his class of 38 in 1857. The position was good enough for him to take a job with the engineers, but there were so many officers in the U.S. Army he had to take a commission as a brevet second lieutenant. It would take over a year before there was enough space on the rolls to make him a full second lieutenant.

In that time he started to head out west to assist in the Utah War (also known as the Mormon War). "In the command," Alexander recalled, "were Capts. Armistead & Dick Garnett, both afterward Confederate generals & both killed in Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg." It would be Alexander who would try to cover the charges of the brigades of Lewis Armisted and Richard Garnett in 1863 in vain with Confederate artillery.

Porter enjoyed the trip west immensely. "...I got my first view of the Rocky Mountains [in] June 1858. They loomed high over the prairies with Pike's, Long's & one or two other snow peaks in sight & impressed my youthful imagination very deeply" he remembered. And also: "I had a glorious chase after my first buffalo." But by the time they got to Colorado, they found the war was over, and Alexander went right back to West Point. He began working on signals and codes, and also met Bettie Mason, a woman he fell madly in love with and married.

He was transferred to Ft. Steilacoom in Washington State, and Alexander and his beloved Miss Teen (as he always referred to Bettie) spent a happy six months there. "Sometimes we had riding or walking excursions or picnics with some of the ladies & sometimes pistol practice for them, & Miss Teen generally beat them all." But trouble was on the horizon.

Of course, as soon as the news of the secession of Georgia reached us at Fort Steilacoom, some three or four weeks after the event, I knew that I would finally have to resign from the U.S. Army. But I did not believe war inevitable & I felt sure I could get a place not inferior in the Southern army, & I really never realized the gravity of the situation. As soon as the right to secede was denied by the North I strongly approved of its assertion & maintenance by force if necessary. And being young & ambitious in my profession I was anxious to take my part in everything going on.As a sign of the more personal nature of Fighting for the Confederacy, Alexander even includes among his farewells a paragraph about the loyalty of a beloved dog he had to leave behind that will be familiar to any modern dog owner. But Alexander also delivers in it a personal explanation for why he fought that buys into the regular states' rights arguments made popular at the time he was writing in Nicaragua.

I told McPherson [his commanding officer] we were going to fight for our "liberty." That was the view the whole South took of it. It was not for slavery but the sovereignty of the states, which is practically the right to resume self government or to secede... Slavery brought up the discussion of the right [to secede] in the Congress and in the press, but the South would never have united as it did in secession & in the war had it not been generally denied in the North & particularly by the Republican part.But Alexander is not content to let it go at that:

The old general stuck in Nicaragua didn't shy from the question for all former Confederates. He said he did not regret his decision, but perhaps the tears Miss Teen shed when he made it made it harder to answer if he would do it again.

Well that was the issue of the war; & as we were defeated that right was surrendered & a limit put on state sovereignty. And the South is now entirely satisfied with that result. And the reason of it is very simple. State sovereignty was doubtless a wise political instution for the condition of this vast country in the last century. But the railroad, and the steamboat & the telegraph began to transform things early in this century & have gradually made what may almost be called a new planet of it... Our political institutions have had to change... Briefly we had the right to fight, but our fight was against what might be called a Darwinian development - or an adaptation to changed & changing conditions - so we need not greatly regret defeat.

When I was young I was willing to take risks & I would take them not only for myself but for those who depended upon me as well. I did not then as fully realize, as I now do, how inexorable are the consequences of mistakes - that sins may be repented of, &, we hope, forgiven, but mistakes laugh at repentance & go on piling up the consequences.The consequences sent newly minted Captain Alexander to Richmond during the month of June, where he waited around for orders. Becoming frustrated at the delay, he finally sent for Miss Teen, the morning before he received the long-delayed orders. He left instructions for her with a friend and boarded the next train to join Beauregard's staff as engineer and signal officer.

I can't fix the exact date of my going to Manassas, but it was about July 1st... I had never met any of them before but his aid Capt. S.W. Ferguson, who had graduated at my class in West Point, having been turned back into it out of the previous class for fighting a cadet officer, Shoup, who had reported him for something. But I was cordially received... & became at home at once. In fact I think Gen. B[eauregard] had more courtesy of manner than any of the other generals with whom I ever served.Over the coming weeks, Alexander would have to make up for lost time and train a signal corps for Beauregard to make sure his army could communicate over the lengths of a large battlefield, while at the same time carrying out the engineer responsibility of carefully mapping the topography of the area.

An observation of Beauregard included in Alexander's account of their first meeting might well serve as a descriptor for the problem the entire Confederacy was about to face as Winfield Scott ramped up military pressure on its shiny new country: "His hair was black, but a few months afterward when some sorts of chemicals & such things became scarce it began to come out quite gray."

Print Sources:

- Fighting for the Confederacy: The Personal Recollections of General Edward Porter Alexander edited by Gary W. Gallagher.

No comments:

Post a Comment