This is the third in a four-part series on the impact of the Mexican War on the American Civil War.

President James K. Polk had a problem: he was winning a war with Mexico. Major General Zachary Taylor, leading the Army of Occupation, had won a victory at the Battle of Monterrey over a much larger Mexican force by out-maneuvering it. Taylor had signed a cease-fire that allowed the Mexicans to retreat from the city, then sat back to rest on his laurels while peace was negotiated. Taylor was being heavily courted by the Whig Party to run for president in two years against Polk's Democratic successor (he had pledged only one term), and the more they courted, the more he felt up to the job.

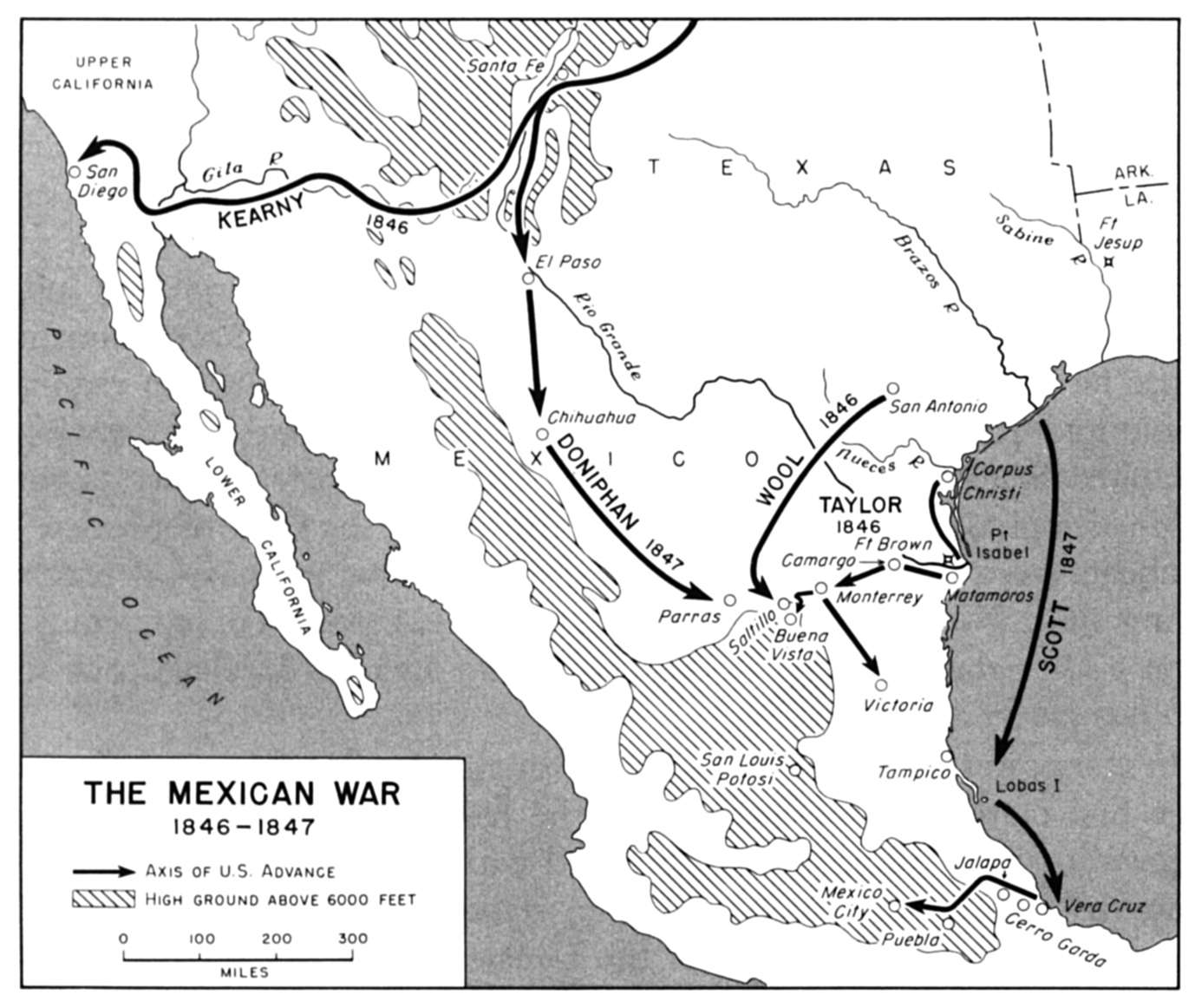

The political problem extended beyond just losing the White House, though. It might just undo all of Polk's schemes to set the Texas border at the Rio Grande and capture the vast area known as Alta California. This area was needed to provide territory for new states to the Union, specifically slave states, in order to counterbalance the growth of free states in the present-day Midwest that pushed economic policies based on manufacturing and trade, and were increasingly harmful to the cash-crop economies of the South. To this end, Polk had dispatched a small Army of the West under Brigadier General Stephen Kearny to seize the power centers Santa Fe and San Diego, but he still needed several more months before Polk could present Mexico City - and the Whigs in the House - a fait accompli.

The answer to Polk's dilemma, lay in the fussy, know-it-all, general-in-chief, Major General Winfield Scott. As early as the initial peacekeeping action in Texas, Scott had been irked by Polk's deliberate snub of him, the senior general in the army. Instead, Polk had chosen the barely literate Taylor to lead the American army in Mexico. Scott was a war-hero already (from 1812), a Whig, and politically connected, so the president had turned to Taylor in hopes of avoiding the creation of a serious political opponent. Now that Taylor had become that, Polk figured he could set up Scott as a rival to the Whig nomination and allow the two to destroy each other. Scott was already on record as fiercely critical of Taylor's handling of the war (Taylor made little to no effort to discipline his men, who took the opportunity to indulge in every vice imaginable), all Polk had to do was acquiesce to the general-in-chief's strategic vision.

Scott had initially opposed war, but since it began he had taken to regularly criticizing Polk's strategy. A thorough student of history, Scott insisted it was ridiculous to think a quick, defensive campaign on the border would be enough to achieve the Mexican government's agreement to surrender over half of the country's territory. Only a well-trained American army marching into Mexico City and forcing a treaty down their throats could achieve that.

To that end, Polk had already ordered a division of volunteers under Brigadier General Robert Patterson to march on the Mexican coastal city of Tampico (without telling Taylor, whose supply line Patterson was supposed to be guarding). When word had first reached Washington in mid-October of Taylor's armistice agreement made two weeks earlier, Polk had flirted with the idea of using Patterson (a good Democrat, though born in Ireland and so ineligible to succeed him) to march on Mexico City, but he had only limited military experience. So he sent a message back to Taylor that the cease-fire was revoked, and to Patterson to hold Tampico for Scott.

Taylor poorly received the order that his cease-fire was canceled at the end of October, and rightly became convinced that Polk was trying to undermine him (ironically, the news finally pushed him over the edge on running for president). While he had holed up in Monterrey, his Mexican opponent had marched south and linked up with Mexico's dictator, General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, to form a new, larger army. Taylor hadn't expected to face them in the field, but now he set the Army of Occupation on a march towards Saltillo, which would be his base of operations for moving into the mountains and valleys of central Mexico. He took only one brigade of the pesky volunteers with him, leaving the increasingly busy Brevet Captain Joe Hooker behind with an ailing Brigadier General Thomas Hamer and his brigade.

In Washington, Scott was trying to get Polk to understand the worthlessness of Tampico for a base of operations. Only Vera Cruz, he insisted, had a port suitable to supply the army needed to take Mexico City. On November 19, as early Congressional mid-term results indicated a landslide for the Whigs (the Whigs eventually would gain 37 seats - including Abraham Lincoln from Illinois - and the Speakership in the House, though they netted -1 seat in the Senate), Polk relented and greenlit an attack on Vera Cruz and an army of 15,000 (4,000 regulars) for Scott's expedition.

By mid-November, Taylor had reached Saltillo. Taylor heard rumors that Patterson might replace him on grounds that he had never had permission to leave Monterrey, but was more upset when he got orders from Scott directing him to send most of his troops (and nearly all of his regulars) back to the coast for transfer to Scott's invasion army. He was cut out.

Hooker, as an ambitious young officer, recognized immediately that he needed to find a way to get himself transferred. In December, when Hamer died of dysentery, he was asked by the division commander to join his staff and jumped at the chance, but the troublesome volunteers were not the force Scott intended to fight his battles with, and Hooker bounced between Monterrey and Saltillo.

Meanwhile, Kearny had at last reached San Diego (and, perplexingly, found American Lt. Colonel John C. Fremont freelancing as dictator of Santa Barbara, starting a very troubled nine month relationship that ended with a court-martial for Fremont). Polk now had accomplished his goals, but by reneging on the cease-fire had to deal with Santa Anna's new army and the inertia of Scott's invasion.

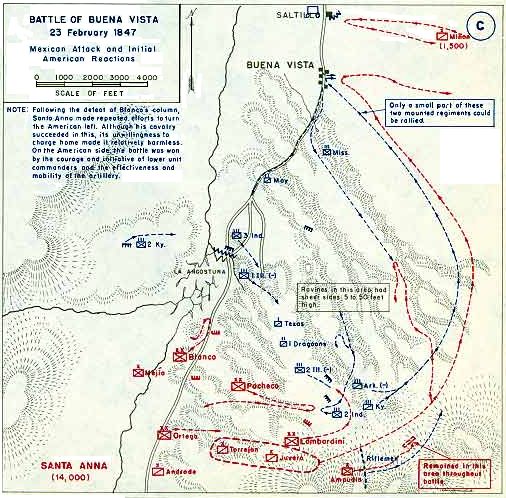

Santa Anna's new army was on the move, too. Deprived of his army, Taylor had decided to make use of someone else's, and ordered the semi-independent force of Brigadier General John Wool to join him in Saltillo (where Wool was met by his new chief-of-staff, Lieutenant Irvin McDowell). Wool's division was 4,500 strong, all volunteers, except for some artillery batteries and the U.S. 1st Dragoons. Taylor placed them in the strategic pass of Buena Vista. On February 23, Santa Anna surprised them with 16,000 Mexicans.

Wool's volunteers stood little chance. In addition to being inexperienced, a vicious fire was rained down on them by heavy cannon operated by the San Patricio Battalion, several hundred immigrant Irishmen that had deserted from the U.S. Army and joined the Mexicans (many because of Taylor's men's brutal treatment of Mexican Catholics and their general hatred of the Irish). The San Patricios made short work of the first unit of volunteers and they began to flee, with Santa Anna ordering a general pursuit. He sent a strong force of Mexican cavalry to rush behind the fleeing men and cut off their retreat.

Taylor showed up when all appeared lost, and with the Mississippi Rifles under Jefferson Davis he obliterated the Mexican cavalry (Taylor was guided by engineer John Pope). Wool (with the invaluable assistance of McDowell) had managed to rally many of his volunteers and was getting them reorganized for another attack, but needed more time. Taylor sent an artillery battery under Captain Braxton Bragg forward with orders to hold at all costs and rode under heavy fire to help him set up at the right spot. "Double-shot your guns and give them hell, Bragg," he ordered in a line that would become legendary (though misquoted as "give them grape" - Bragg's batter carried no grape). The heroic work of Bragg and his guns (including one managed by John Reynolds) paid off, and Wool's volunteers drove the Mexicans from the field with only the murderous fire of the San Patricio's saving Santa Anna from a rout.

The immediate fallout was two-fold: Santa Anna had to abandon most of his army in order to make it back to Mexico City in time to suppress a coup, and Taylor achieved celebrity status back home. Davis - who had been Taylor's son-in-law before the tragic death of Sarah Taylor Davis, which is why the general trusted him - also became a celebrity, and in six months would be U.S. Senator from Mississippi. He would never forget the heroic work of Bragg, forming a tight relationship that would later bedevil the Confederate war command.

Hooker, back in Monterrey, hoped alcohol and loose women would help him dull the pain of having missed out on what might have been his last great chance at greatness. He vowed to somehow obtain a crucial role in Scott's expedition.

Print Sources:

|

| Buena Vista, from an 1847 sketch by Maj. Eaton, aide-de-camp to Gen. Taylor |

President James K. Polk had a problem: he was winning a war with Mexico. Major General Zachary Taylor, leading the Army of Occupation, had won a victory at the Battle of Monterrey over a much larger Mexican force by out-maneuvering it. Taylor had signed a cease-fire that allowed the Mexicans to retreat from the city, then sat back to rest on his laurels while peace was negotiated. Taylor was being heavily courted by the Whig Party to run for president in two years against Polk's Democratic successor (he had pledged only one term), and the more they courted, the more he felt up to the job.

The political problem extended beyond just losing the White House, though. It might just undo all of Polk's schemes to set the Texas border at the Rio Grande and capture the vast area known as Alta California. This area was needed to provide territory for new states to the Union, specifically slave states, in order to counterbalance the growth of free states in the present-day Midwest that pushed economic policies based on manufacturing and trade, and were increasingly harmful to the cash-crop economies of the South. To this end, Polk had dispatched a small Army of the West under Brigadier General Stephen Kearny to seize the power centers Santa Fe and San Diego, but he still needed several more months before Polk could present Mexico City - and the Whigs in the House - a fait accompli.

The answer to Polk's dilemma, lay in the fussy, know-it-all, general-in-chief, Major General Winfield Scott. As early as the initial peacekeeping action in Texas, Scott had been irked by Polk's deliberate snub of him, the senior general in the army. Instead, Polk had chosen the barely literate Taylor to lead the American army in Mexico. Scott was a war-hero already (from 1812), a Whig, and politically connected, so the president had turned to Taylor in hopes of avoiding the creation of a serious political opponent. Now that Taylor had become that, Polk figured he could set up Scott as a rival to the Whig nomination and allow the two to destroy each other. Scott was already on record as fiercely critical of Taylor's handling of the war (Taylor made little to no effort to discipline his men, who took the opportunity to indulge in every vice imaginable), all Polk had to do was acquiesce to the general-in-chief's strategic vision.

Scott had initially opposed war, but since it began he had taken to regularly criticizing Polk's strategy. A thorough student of history, Scott insisted it was ridiculous to think a quick, defensive campaign on the border would be enough to achieve the Mexican government's agreement to surrender over half of the country's territory. Only a well-trained American army marching into Mexico City and forcing a treaty down their throats could achieve that.

To that end, Polk had already ordered a division of volunteers under Brigadier General Robert Patterson to march on the Mexican coastal city of Tampico (without telling Taylor, whose supply line Patterson was supposed to be guarding). When word had first reached Washington in mid-October of Taylor's armistice agreement made two weeks earlier, Polk had flirted with the idea of using Patterson (a good Democrat, though born in Ireland and so ineligible to succeed him) to march on Mexico City, but he had only limited military experience. So he sent a message back to Taylor that the cease-fire was revoked, and to Patterson to hold Tampico for Scott.

Taylor poorly received the order that his cease-fire was canceled at the end of October, and rightly became convinced that Polk was trying to undermine him (ironically, the news finally pushed him over the edge on running for president). While he had holed up in Monterrey, his Mexican opponent had marched south and linked up with Mexico's dictator, General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, to form a new, larger army. Taylor hadn't expected to face them in the field, but now he set the Army of Occupation on a march towards Saltillo, which would be his base of operations for moving into the mountains and valleys of central Mexico. He took only one brigade of the pesky volunteers with him, leaving the increasingly busy Brevet Captain Joe Hooker behind with an ailing Brigadier General Thomas Hamer and his brigade.

In Washington, Scott was trying to get Polk to understand the worthlessness of Tampico for a base of operations. Only Vera Cruz, he insisted, had a port suitable to supply the army needed to take Mexico City. On November 19, as early Congressional mid-term results indicated a landslide for the Whigs (the Whigs eventually would gain 37 seats - including Abraham Lincoln from Illinois - and the Speakership in the House, though they netted -1 seat in the Senate), Polk relented and greenlit an attack on Vera Cruz and an army of 15,000 (4,000 regulars) for Scott's expedition.

By mid-November, Taylor had reached Saltillo. Taylor heard rumors that Patterson might replace him on grounds that he had never had permission to leave Monterrey, but was more upset when he got orders from Scott directing him to send most of his troops (and nearly all of his regulars) back to the coast for transfer to Scott's invasion army. He was cut out.

Hooker, as an ambitious young officer, recognized immediately that he needed to find a way to get himself transferred. In December, when Hamer died of dysentery, he was asked by the division commander to join his staff and jumped at the chance, but the troublesome volunteers were not the force Scott intended to fight his battles with, and Hooker bounced between Monterrey and Saltillo.

Meanwhile, Kearny had at last reached San Diego (and, perplexingly, found American Lt. Colonel John C. Fremont freelancing as dictator of Santa Barbara, starting a very troubled nine month relationship that ended with a court-martial for Fremont). Polk now had accomplished his goals, but by reneging on the cease-fire had to deal with Santa Anna's new army and the inertia of Scott's invasion.

Santa Anna's new army was on the move, too. Deprived of his army, Taylor had decided to make use of someone else's, and ordered the semi-independent force of Brigadier General John Wool to join him in Saltillo (where Wool was met by his new chief-of-staff, Lieutenant Irvin McDowell). Wool's division was 4,500 strong, all volunteers, except for some artillery batteries and the U.S. 1st Dragoons. Taylor placed them in the strategic pass of Buena Vista. On February 23, Santa Anna surprised them with 16,000 Mexicans.

Wool's volunteers stood little chance. In addition to being inexperienced, a vicious fire was rained down on them by heavy cannon operated by the San Patricio Battalion, several hundred immigrant Irishmen that had deserted from the U.S. Army and joined the Mexicans (many because of Taylor's men's brutal treatment of Mexican Catholics and their general hatred of the Irish). The San Patricios made short work of the first unit of volunteers and they began to flee, with Santa Anna ordering a general pursuit. He sent a strong force of Mexican cavalry to rush behind the fleeing men and cut off their retreat.

Taylor showed up when all appeared lost, and with the Mississippi Rifles under Jefferson Davis he obliterated the Mexican cavalry (Taylor was guided by engineer John Pope). Wool (with the invaluable assistance of McDowell) had managed to rally many of his volunteers and was getting them reorganized for another attack, but needed more time. Taylor sent an artillery battery under Captain Braxton Bragg forward with orders to hold at all costs and rode under heavy fire to help him set up at the right spot. "Double-shot your guns and give them hell, Bragg," he ordered in a line that would become legendary (though misquoted as "give them grape" - Bragg's batter carried no grape). The heroic work of Bragg and his guns (including one managed by John Reynolds) paid off, and Wool's volunteers drove the Mexicans from the field with only the murderous fire of the San Patricio's saving Santa Anna from a rout.

The immediate fallout was two-fold: Santa Anna had to abandon most of his army in order to make it back to Mexico City in time to suppress a coup, and Taylor achieved celebrity status back home. Davis - who had been Taylor's son-in-law before the tragic death of Sarah Taylor Davis, which is why the general trusted him - also became a celebrity, and in six months would be U.S. Senator from Mississippi. He would never forget the heroic work of Bragg, forming a tight relationship that would later bedevil the Confederate war command.

Hooker, back in Monterrey, hoped alcohol and loose women would help him dull the pain of having missed out on what might have been his last great chance at greatness. He vowed to somehow obtain a crucial role in Scott's expedition.

Print Sources:

- Eagles and Empire: The United States, Mexico, and the Struggle for a Continent by David A. Cleary

- Fighting Joe Hooker by Walter H. Herbert

- The Battle Cry of Freedom by James McPherson

No comments:

Post a Comment